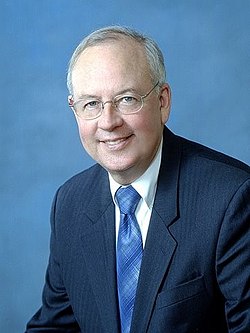

Ken Starr

Ken Starr | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Independent Counsel for the Whitewater Controversy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office August 5, 1994 – September 11, 1998 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Robert B. Fiske (Special Counsel) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Robert Ray | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39th Solicitor General of the United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office May 26, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | George H. W. Bush | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | John Roberts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Charles Fried | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Drew S. Days III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office September 20, 1983 – May 26, 1989 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appointed by | Ronald Reagan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | George MacKinnon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Karen L. Henderson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Kenneth Winston Starr July 21, 1946 Vernon, Texas, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | September 13, 2022 (aged 76) Houston, Texas, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Democratic (before 1975) Republican (1975–2022) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Alice Mendell (m. 1970) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kenneth Winston Starr (July 21, 1946 – September 13, 2022) was an American lawyer and judge who as independent counsel authored the Starr Report, which served as the basis of the impeachment of Bill Clinton. He headed an investigation of members of the Clinton administration, known as the Whitewater controversy, from 1994 to 1998. Starr previously served as a federal appellate judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit from 1983 to 1989 and as the U.S. solicitor general from 1989 to 1993 during the presidency of George H. W. Bush.

Starr received the most public attention for his tenure as independent counsel while Bill Clinton was U.S. president. Starr was initially appointed to investigate the suicide of deputy White House counsel Vince Foster and the Whitewater real estate investments of Clinton. The three-judge panel charged with administering the Ethics in Government Act later expanded the inquiry into numerous areas including suspected perjury about Clinton's sexual affair with Monica Lewinsky. After more than four years of investigation, Starr filed the Starr Report, which alleged that Clinton lied about the existence of the affair during a sworn deposition. The allegation led to the impeachment of Clinton and the five-year suspension of Clinton's Arkansas law license.

Starr served as the dean of the Pepperdine University School of Law.[1][2][3] He was later both the president and the chancellor of Baylor University in Waco, Texas, from June 2010 until May and June 2016, respectively, and at the same time the Louise L. Morrison chair of constitutional law at Baylor Law School. On May 26, 2016, following an investigation into the mishandling by Starr of several sexual assaults at the school, Baylor University's board of regents announced that Starr's tenure as university president would end on May 31.[4] The board said he would continue as chancellor, but on June 1, Starr resigned that position with immediate effect.[5] On August 19, 2016, Starr announced he would also resign from his tenured professor position at Baylor Law School, completely severing his ties with the university in a "mutually agreed separation",[6] following accusations that he ignored allegations of sexual assault on campus.[4] On January 17, 2020, Starr joined President Donald Trump's legal team during his first impeachment trial.[7][8]

Early life and education

[edit]Starr was born near Vernon, Texas, the son of Vannie Maude (Trimble) and Willie D. Starr, and was raised in Centerville, Texas.[9][10] His father was a minister in the Churches of Christ who also worked as a barber.[11] Starr attended Sam Houston High School in San Antonio and was a popular, straight‑A student. His classmates voted him most likely to succeed.[12][13] In 1970, Starr married Alice Mendell, who was raised Jewish but converted to Christianity.[14][15][16] They had three children.[17]

Starr attended the Churches of Christ–affiliated Harding University in Searcy, Arkansas, where he was an honor student, a member of the Young Democrats,[12] and a vocal supporter of Vietnam protesters.[18] He later transferred to George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., where he received a Bachelor of Arts in history, in 1968. While there, he became a member of Delta Phi Epsilon.[19]

Starr was not drafted for military service during the Vietnam War, as he was classified 4‑F, because he had psoriasis.[20] He worked in the Southwestern Advantage entrepreneurial program and later attended Brown University, where he earned a Master of Arts degree in 1969. Starr then attended the Duke University School of Law, where he was an editor of the Duke Law Journal and graduated with a Juris Doctor in 1973.[21]

Legal career

[edit]After he graduated from law school, Starr was a law clerk to judge David W. Dyer of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit from 1973 to 1974.[16] From 1975 to 1977, he clerked for chief justice Warren E. Burger of the U.S. Supreme Court.[16]

In 1977, Starr joined the Washington, D.C., office of the Los Angeles–based law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher (now Gibson Dunn).[22] In 1981 he was appointed counselor to U.S. attorney general William French Smith.[16]

Starr was a member of the Federalist Society.[23]

Federal judge and solicitor general

[edit]

On September 13, 1983, he was nominated by Ronald Reagan to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated by George MacKinnon. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on September 20, 1983, and received his commission on September 20, 1983. He resigned on May 26, 1989.[24]

Starr was the United States solicitor general, from 1989 to 1993, under George H. W. Bush.[24]

Early 1990s

[edit]When the United States Senate Select Committee on Ethics needed someone to review Republican senator Bob Packwood's diaries, the committee chose Starr.[25] In 1990, Starr was the leading candidate for the U.S. Supreme Court nomination after William Brennan's retirement. He encountered strong resistance from the Department of Justice leadership, which feared Starr might not be reliably conservative as a Supreme Court justice. George H. W. Bush nominated David Souter instead of Starr.[26] Starr also considered running for the United States Senate, from Virginia in 1994, against incumbent Chuck Robb, but opted against opposing Oliver North for the Republican nomination.[27]

Independent counsel

[edit]

Appointment

[edit]In August 1994, pursuant to the newly reauthorized Ethics in Government Act (28 U.S.C. § 593(b)), Starr was appointed by a special three-judge division of the D.C. Circuit to continue the Whitewater investigation.[28] He replaced Robert B. Fiske, a moderate Republican who had been appointed by attorney general Janet Reno.[29]

Starr took the position part-time and remained active with his law firm, Kirkland & Ellis, as this was permitted by statute and was also the norm with previous independent counsel investigations.[30][31] As time went on, he was increasingly criticized for alleged conflicts of interest stemming from his continuing association with Kirkland & Ellis.[30] Kirkland, like several other major law firms, was representing clients in litigation with the government, including tobacco companies and auto manufacturers.[32] The firm itself was being sued by the Resolution Trust Corporation, a government agency involved in the Whitewater matter. Additionally, Starr's own actions were challenged because Starr had, on one occasion, talked with lawyers for Paula Jones, who was suing Bill Clinton over an alleged sexual harassment.[32] Starr had explained to them why he believed that sitting U.S. Presidents are not immune to civil suit.[32] When this constitutional question ultimately reached the Supreme Court, the justices unanimously agreed.[citation needed]

Investigation of the death of Vince Foster

[edit]On October 10, 1997, Starr's report on the death of deputy White House counsel Vince Foster, drafted largely by Starr's deputy Brett Kavanaugh, was released to the public by the Special Division. The complete report is 137 pages long and includes an appendix added to the Report by the Special Division over Starr's objection.[33] The report agrees with the findings of previous independent counsel Robert B. Fiske that Foster committed suicide at Fort Marcy Park, in Virginia, and that his suicide was caused primarily by undiagnosed and untreated depression. As CNN explained on February 28, 1997, "The [Starr] report refutes claims by conservative political organizations that Foster was the victim of a murder plot and coverup," but "despite those findings, right-wing political groups have continued to allege that there was more to the death and that the president and first lady tried to cover it up."[34] CNN also noted that organizations pushing the murder theory included the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, owned by billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife, and Accuracy in Media, supported in part by Scaife's foundation.[35] Scaife's reporter on the Whitewater matter, Christopher Ruddy, was a frequent critic of Starr's handling of the case.[36]

Expansion of the investigation

[edit]The law conferred broad investigative powers on Starr and the other independent counsels named to investigate the administration, including the right to subpoena nearly anyone who might have information relevant to the particular investigation.[37] Starr would later receive authority to conduct additional investigations, including the firing of White House Travel Office personnel, potential political abuse of confidential FBI files, Madison Guaranty, Rose Law Firm, Paula Jones lawsuit and, most notoriously, possible perjury and obstruction of justice to cover up President Clinton's sexual relationship with Monica Lewinsky.[38] The Lewinsky portion of the investigation included the secret taping of conversations between Lewinsky and coworker Linda Tripp, requests by Starr to tape Lewinsky's conversations with Clinton, and requests by Starr to compel Secret Service agents to testify about what they might have seen while guarding Clinton. With the investigation of Clinton's possible adultery, critics of Starr believed that he had crossed a line and was acting more as a political hit man than as a prosecutor.[37][39]

Clinton–Lewinsky scandal, Paula Jones lawsuit

[edit]In his deposition for the Paula Jones lawsuit, Clinton denied having "sexual relations" with Monica Lewinsky.[40] On the basis of the evidence provided by Monica Lewinsky, a blue dress stained with Clinton's semen, Ken Starr concluded that this sworn testimony was false and perjurious.[40][41]

During the deposition in the Jones case, Clinton was asked, "Have you ever had sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky, as that term is defined in Deposition Exhibit 1, as modified by the Court?" The definition included contact with the genitalia, anus, groin, breast, inner thigh, or buttocks of a person with an intent to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of that person, any contact of the genitals or anus of another person, or contact of one's genitals or anus and any part of another person's body either directly or through clothing.[41][40][42] The judge ordered that Clinton be given an opportunity to review the agreed definition. Clinton flatly denied having sexual relations with Lewinsky.[43] Later, at the Starr grand jury, Clinton stated that he believed the definition of "sexual relations" agreed upon for the Jones deposition excluded his receiving oral sex.[40]

Starr's investigation eventually led to the impeachment of President Clinton, with whom Starr shared Time's Man of the Year designation for 1998.[38][44] Following his impeachment, the president was acquitted in the subsequent trial before the United States Senate as all 45 Democrats and 10 Republicans voted to acquit.[45]

Second thoughts on DOJ request

[edit]In 2004, Starr expressed regret for ever having asked the Department of Justice to assign him to oversee the Lewinsky investigation personally, saying, "the most fundamental thing that could have been done differently" would have been for somebody else to have investigated the matter.[46]

Criticism and political satire

[edit]As with many controversial figures, Kenneth Starr was the subject of political satire. For example, the book, And the Horse He Rode in On by James Carville attempted to portray Mr. Starr's time as special prosecutor in comically negative light.

Post-independent counsel activities

[edit]

After five years as independent counsel, Starr resigned and returned to private practice as an appellate lawyer and a visiting professor at New York University, the Chapman University School of Law, and the George Mason University School of Law.[47] Starr worked as a partner at Kirkland & Ellis, specializing in litigation.[48] He was one of the lead attorneys in a class-action lawsuit filed by a coalition of liberal and conservative groups (including the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Rifle Association of America) against the regulations created by the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, known informally as McCain-Feingold Act.[49]

On April 6, 2004, he was appointed dean of the Pepperdine University School of Law.[50] He originally accepted a position at Pepperdine as the first dean of the newly created School of Public Policy in 1996. He withdrew from the appointment in 1998, several months after the Lewinsky controversy erupted.[51] Critics charged that there was a conflict of interest due to substantial donations to Pepperdine from billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife, a Clinton critic who funded many media outlets attacking the president.[35] In 2004, some five years after President Clinton's impeachment, Starr was again offered a Pepperdine position at the School of Law and this time accepted it.[50]

Death penalty cases

[edit]In 2005, Starr worked to overturn the death sentence of Robin Lovitt, who was on Virginia's death row for murdering a man during a robbery in 1998.[52] Starr provided his services to Lovitt pro bono.[52] On October 3, 2005, the Supreme Court denied certiorari.[52]

On January 26, 2006, the defense team of convicted murderer Michael Morales (which included Starr) sent letters to California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger requesting clemency for Morales.[53] Letters purporting to be from the jurors who determined Morales's death sentence were included in the package sent to Schwarzenegger. Prosecutors alleged that the documents were forgeries, and accused investigator and anti-death penalty activist Kathleen Culhane of falsifying the documents.[53] Lead defense attorney David Senior and his team soon withdrew the documents.[53] Ultimately, clemency was denied, but the falsified documents were not used in the rationale.[54] Eventually, Culhane was criminally charged with forging the documents and, under a plea agreement, was sentenced to five years in prison.[55]

Morse v. Frederick

[edit]On May 4, 2006, Starr announced that he would represent the school board of Juneau, Alaska, in its appeal to the United States Supreme Court in a case brought by a former student, Joseph Frederick.[56] A high school student at that time, Joseph Frederick unfurled a banner at a school-sponsored event saying "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" as the Olympic torch was passing through Juneau, before arriving in Salt Lake City, Utah, for the 2002 Winter Olympics.[56] The board decided to suspend the student.[56] The student then sued and won at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which stated that the board violated the student's first amendment right to free speech.[56] On August 28, 2006, Starr filed a writ of certiorari for a hearing with the Supreme Court.[57] On June 21, 2007, in an opinion authored by Chief Justice John G. Roberts, the court ruled in favor of Starr's client, finding that "a principal may, consistent with the First Amendment, restrict student speech at a school event, when that speech is reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use."[58]

Blackwater Security Consulting v. Nordan (No. 06-857)

[edit]Starr represented Blackwater in a case involving the deaths of four unarmed civilians killed by Blackwater contractors in Fallujah, Iraq, in March 2004.[59]

California Proposition 8 post-election lawsuits

[edit]On December 19, 2008, Proposition 8 supporters named Starr to represent them in post-election lawsuits to be heard by the Supreme Court of California.[60] Opponents of the measure sought to overturn it as a violation of fundamental rights, while supporters sought to invalidate the 18,000 same-sex marriages performed in the state before Proposition 8 passed.[60] Oral arguments took place on March 5, 2009, in San Francisco.[61]

Starr argued that "Prop. 8 was a modest measure that left the rights of same-sex couples undisturbed under California's domestic-partner laws and other statutes banning discrimination based on sexual orientation," to the agreement of most of the judges.[61] The main issue that arose during the oral argument included the meaning of the word "inalienable," and to which extent this word goes when used in Article I of the Californian Constitution.[61] Christopher Krueger of the attorney general's office said that inalienable rights may not be stripped away by the initiative process. Starr countered that "rights are important, but they don't go to structure ... rights are ultimately defined by the people."[62]

The court ultimately held that the measure was valid and effective, but would not be applied retroactively to marriages performed prior to its enactment.[63]

Starr was an advisory board member for the legal organization Alliance Defending Freedom.[64]

Defense of Jeffrey Epstein

[edit]In 2007, Starr joined the legal team defending Palm Beach billionaire Jeffrey Epstein, who was accused of the statutory rape of numerous underage high school students.[65] Epstein would later plea bargain to plead guilty to several charges of soliciting and trafficking of underage girls, serve 13 months on work release in a private wing of the Palm Beach jail, and register as a sex offender.[66] Starr said he was "in the room" when then-US attorney Alex Acosta made the deal that yielded the plea bargain for Epstein and later described Acosta as "a person of complete integrity," adding that "everyone was satisfied" with the agreement.[67]

Donald Trump impeachment trial

[edit]On January 16, 2020, Starr was announced as a member of then-President Donald Trump's legal team for his Senate impeachment trial.[68] He argued before the Senate on Trump's behalf on January 27, 2020.[69] Slate journalist Jeremy Stahl pointed out that as he was urging the Senate not to remove Trump as president, Starr contradicted various arguments he used in 1998 to justify Clinton's impeachment.[69] In defending Trump, Starr also claimed he was wrong to have called for impeachment against Clinton for abuse of executive privilege and efforts to obstruct Congress and also stated that the House Judiciary Committee was right in 1998 to have rejected one of the planks for impeachment he had advocated for.[69] He also invoked a 1999 Hofstra Law Review article by Yale law professor Akhil Amar, who argued that the Clinton impeachment proved just how impeachment and removal causes "grave disruption" to a national election.[69] Starr was called as a witness by Sen. Ron Johnson on a senate hearing concerning electoral fraud amidst Trump's attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election.[70] When Trump was impeached for a second time in 2021, Starr condemned the impeachment as "dangerous" and "unconstitutional".[71]

Baylor University

[edit]

Starr was the Duane and Kelly Roberts Dean and Professor of Law at Pepperdine University, when on February 15, 2010, Baylor University announced that it would introduce Starr as its newest president.[15] Starr became Baylor's 14th president, replacing John Lilley who was ousted in mid‑2008.[72] Starr was introduced as the new president on June 1, 2010.[73]

His inauguration was held on September 17, 2010, where Stephen L. Carter was the keynote speaker.[74] Within his first two weeks in office, Starr was "leading the charge" to keep the university in the Big 12 Conference for athletics.[75] Starr was additionally named chancellor of Baylor in November 2013, a post that had been vacant since 2005. He became the first person to hold the positions of president and chancellor at Baylor at the same time.[76]

In September 2015, Baylor's Board of Regents initiated an external review of the university's response to reports of sexual violence to be conducted by the Pepper Hamilton law firm. Baylor had been accused of failing to respond to reports of rape and sexual assault filed by at least six female students from 2009 to 2016. Former football player Tevin Elliot was convicted of rape. Elliot is currently serving a 20-year sentence after his conviction in January 2014.[77] Another student, Sam Ukwuachu, was convicted but has since had that conviction overturned and was retried, only to see it reinstated by the Texas Court of Appeals in 2018.[78] Pepper Hamilton reported their findings to the regents on May 13, 2016,[79] and on May 26, the regents announced Starr's removal as university president, effective May 31.[80]

The May 26, 2016, announcement of personnel changes by the Board of Regents said Starr was to have continued as Chancellor and also as a faculty member at Baylor Law School.[5] Starr announced his resignation as Chancellor on June 1, effective immediately.[5] He told an interviewer that he took that action "as a matter of conscience."[5] He said he "willingly accepted responsibility" and "The captain goes down with the ship."[5] He resigned his position as the Louise L. Morrison Chair of Constitutional Law in Baylor Law School on August 19, 2016.[81]

Death

[edit]In May 2022, Starr was admitted to Baylor St. Luke's Medical Center in Houston, due to an unspecified illness.[82] He died there from complications from surgery on September 13, 2022, at the age of 76.[38][83]

Bibliography

[edit]- First Among Equals: The Supreme Court in American Life. Grand Central Publishing. 2002. ISBN 978-0-446-52756-9.

- Starr, Ken (2018). Contempt: A Memoir of the Clinton Investigation. Penguin. ISBN 9780525536130.

- Starr, Ken (2021). Religious Liberty in Crisis: Exercising Your Faith in an Age of Uncertainty. Encounter Books. ISBN 9781641771801.

See also

[edit]- George H. W. Bush Supreme Court candidates

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Chief Justice)

References

[edit]- ^ "TaxProf Blog: Pepperdine Dean Ken Starr Named President of Baylor". taxprof.typepad.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "Ken Starr named dean of Pepperdine School of Law". pepperdine-graphic.com. April 2004. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "TaxProf Blog: Tom Bost Named Interim Dean at Pepperdine". taxprof.typepad.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Schuknecht, Cat (January 18, 2020). "After a Fall at Baylor, Ken Starr Became a Fox Regular, and then, A Trump Defender". NPR.org. NPR. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Kenneth Starr stepping down as Baylor chancellor". ESPN. June 1, 2016. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ "Former Baylor president Ken Starr leaving university's faculty". wfaa.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ Collins, Kaitlin; Brown, Pamela; Liptak, Kevin (January 17, 2020). "Trump adds Ken Starr and Alan Dershowitz to impeachment defense team". CNN. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Baker, Peter (January 17, 2020). "Ken Starr Returns to the Impeachment Fray, This Time for the Defense". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Vannie Mae Starr, Prosecutor's Mother". sun-sentinel.com. Sun Sentinel. December 30, 1998. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Starr, Kenneth W(inston) 1946–". encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Kenneth W. Starr, Former Federal Judge and U.S. Solicitor General, Dies at 76" (Press release). PR Newswire. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Pressley, Sue Anne (February 3, 1998). "Special Report: The Roots of Ken Starr's Morality Plays". Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Black, Jane (November 9, 1998). "Kenneth Starr: On the trail of the President". BBC. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Mark (May 7, 2010). "Kenneth Starr Tries to Help Baylor Move On". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Ross, Bobby Jr. (February 2010). "Pepperdine Law Dean Kenneth Starr named president of Baylor". Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 18, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Woods, Tim (February 16, 2010). "Ken Starr named president of Baylor University". Waco Tribune-Herald. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Witherspoon, Tommy (September 13, 2022). "'A scholar and a gentleman': Former Baylor president, Clinton investigator Ken Starr dead at 76". www.kwtx.com. Gray Television, Inc. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Manes, David M (September 9, 2008). "Kenneth Starr in The Bison at Harding College". politicalcartel.org. The Political Cartel Foundation. Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Eta Chapter of Delta Phi Epsilon". Delta Phi Epsilon. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Winerip, Michael (September 6, 1998). "Ken Starr Would Not Be Denied". The New York Times. p. 36. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Chu, Kathy (July 21, 2006). "College students learn from job of hard knocks". USA Today. Gannett Co. Inc. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Background: Kenneth W. Starr". Dallas Morning News. February 2010. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ DeParle, Jason (August 1, 2005). "Debating the Subtle Sway of the Federalist Society". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ a b "Starr, Kenneth Winston". fjc.gov. Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Congress Winds Down: The Senate – Investigation Of Packwood Is Lagging, Panel Reports". The New York Times. October 8, 1994. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford (2008). Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court. Penguin. pp. 89–93. ISBN 978-0-14-311304-1.

- ^ "Starr Trek?". Newsweek. February 14, 1993. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ In re GRAND JURY SUBPOENAS DUCES TECUM, 78 F.3d 1307 Archived May 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (8th Cir. 1996)

- ^ "Judicial Panel Names New Whitewater Independent Counsel (transcript)". ABC World News Tonight. American Broadcasting Company. May 8, 1994.

- ^ a b "Kenneth Starr". kirkland.com. Kirkland & Ellis LLP. Archived from the original on November 3, 2006.

- ^ "Kenneth W. Starr - Of Counsel". kirkland.com. Kirkland & Ellis LLP. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Appendix to the Report on the Death of Vincent W. Foster, Jr. Vol. 2 has title:Appendix to Report on the death of Vincent W. Foster, Jr., containing comments of Kevin Fornshill, Helen Dickey, and Patrick Knowlton. Vol. 2. HATHI trust digital library, Purdue University. 1997. ISBN 9780160492747. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016.

- ^ "Report: Starr Rules Out Foul Play In Foster Death". All Politics. CNN. February 23, 1997. Archived from the original on June 9, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Jackson, Brookes (April 27, 1998). "Who Is Richard Mellon Scaife?". CNN. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Jurkowitz, Mark (February 26, 1998). "The Right's Daddy Morebucks; Billionaire's cash fuels conservative journalism's fires". The Boston Globe. New York Times Co. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Lacayo, Richard; Cohen, Adam (February 9, 1998). "Inside Starr and His Operation". Time. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Kenneth W. Starr, Former Federal Judge and U.S. Solicitor General, Dies at 76" (Press release). Yahoo. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Froomkin, Dan. "Untangling Whitewater". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c d King, John (May 3, 1998). "New Details Of Clinton's Jones Deposition Leaked". CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "President Clinton's Deposition in the Paula Jones Case". Washington Post. January 17, 1998. Archived from the original on January 16, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Hentoff, Nat (January 29, 2001). "Above the law; Bill Clinton gets away with perjury (editorial)". The Washington Times. The Washington Times LLC.

- ^ "Nature of President Clinton's Relationship with Monica Lewinsky". The Starr Report. Office of the Independent Counsel, US Government Printing Office. August 9, 1998. Archived from the original on December 3, 2000. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Bill Clinton and Kenneth Starr". Time. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ See Impeachment of Bill Clinton#Trial before U.S. Senate.

- ^ "Starr regrets lead role in Clinton investigation". Deseret News. December 4, 2004. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022.

- ^ "Ken Starr Bio" (PDF). UNLV.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Soon to Be Jobless, Starr Has Winning Appeal". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Kenneth Starr Joins Leaders from NRA, Americans United and ACLU to Find Common Ground on Civil Liberties". ACLU. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Kenneth Starr, Dean of Pepperdine Law, To Speak at CLS". Columbia Law. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Whitewater Counsel's University Surprise Had Origins in Discussions Last Fall". Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Robin Lovitt". American Bar. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c Elias, Paul (January 27, 2006). "Ken Starr asks governor to spare condemned killer". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "Governor turns down killer's bid for clemency / Morales running out of options as Tuesday's execution nears". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (August 17, 2007). "Death penalty foe gets five years in prison". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Starr to take on appeal over "bong" banner". The Seattle Times. The Seattle Times Company. Associated Press. April 5, 2006. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Juneau School Board (August 28, 2006). "Petition for Writ of Certiorari" (PDF). On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Supreme Court of the United States (June 25, 2007). "Morse et al. v. Frederick" (PDF). Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ "High Court Asked to Explore Contractor Liability for Deaths in Iraq". Law.com. February 22, 2007. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Egelko, Bob (December 20, 2008). "Brown asks state high court to overturn Prop. 8". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c Egelko, Bob (March 5, 2009). "Justices seem to be leaning in favor of Prop. 8". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Richman, Josh (March 5, 2009). "California Supreme Court hears Prop. 8 arguments". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Keys, Matthew (August 4, 2010). "Federal Judge: Same Sex Marriage Ban Under Proposition 8 Violates Constitution". FOX40.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012.

- ^ "ADF celebrates extraordinary life of Judge Ken Starr, religious liberty champion". Alliance Defending Freedom Legal. September 14, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ "Lewinsky prosecutor joins defense of Clinton crony". Palm Beach Post. September 12, 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012.

- ^ "How the billionaire pedophile got off easy". Daily Beast. March 25, 2011. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Former Epstein attorney Ken Starr says Alex Acosta played tough in 2008". Fox News. July 13, 2019. Archived from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ McCarthy, Tom (January 17, 2020). "Alan Dershowitz and Ken Starr join Trump impeachment legal team". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Stahl, Jeremy (January 27, 2020). "Ken Starr Argues There Are Too Many Impeachments These Days". Slate. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Qiu, Linda (December 16, 2020). "The election is over, but Ron Johnson keeps promoting false claims of fraud". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Chiarello, Roman (February 10, 2021). "Ken Starr says Trump's second impeachment 'unconstitutional' and sets 'dangerous precedent'". Fox News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Angela K. (February 16, 2010). "Ex-Clinton prosecutor Starr named Baylor president". Avalanche-Journal. Lubbock, Texas. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Woods, Tim Ken Starr to meet Baylor faculty, staff, students today Archived April 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Waco Tribune-Herald, 2010 June 1 (accessed 2010 June 13).

- ^ The Inauguration of Kenneth Winston Starr Archived September 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Baylor University.

- ^ Woods, Tim Starr's first days: Possible Big 12 breakup hands new Baylor president an early crisis Archived March 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Waco Tribune-Herald, 2010 June 13 (accessed 2010 June 13).

- ^ Dennis, Regina (November 12, 2013). "Baylor President Starr's contract extended, chancellor added to title". Waco Tribune. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ "Report: Baylor board of regents fires president Ken Starr". Sports Illustrated. May 24, 2016. Archived from the original on May 25, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Ukwuachu's conviction reinstated on appeal". ESPN.com. June 6, 2018. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ "Reports: Baylor to fire president Ken Starr over sex assaults scandal". WFAA-ABC 8. May 24, 2016. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Baylor University Board of Regents announces leadership changes and extensive corrective actions following findings of external investigation" (Press release). Baylor University. May 26, 2016. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "Judge Ken Starr[permanent dead link]". Faculty & Staff Directory. Baylor University. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Baker, Peter (September 14, 2022). "Ken Starr, Whose Investigation Led to Clinton's Impeachment, Dies at 76". The New York Times. p. B10. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ "Ken Starr, prosecutor in Clinton Whitewater probe, dies at 76". CNBC. September 13, 2022. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Clinton, Bill (2005). My Life. Vintage. ISBN 1-4000-3003-X.

- Conason, Joe and Lyons, Gene (2000). The Hunting of the President. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-27319-3.

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford (2006). Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court. Penguin Books, ISBN 978-1-59420-101-1.

- Schmidt, Susan and Weisskopf, Michael (2000). Truth at Any Cost: Ken Starr and the Unmaking of Bill Clinton. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-019485-5.

- St. George, Donna (March 14, 2005). "Starr, in New Role, Gives Hope to a Needy Death Row Inmate". The Washington Post.

External links

[edit]- Kenneth Winston Starr at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Office of the President at Baylor University

- Profile at the Wayback Machine (archived February 15, 2007) at the U.S. Department of Justice

- Ken Starr at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Cases argued before the Supreme Court at Oyez.org

- Lobbyist record (2001–2002) at OpenSecrets

- 2008 Interview with Kenneth Starr on hossli.com

- Report on the Death of Vincent W. Foster, Jr, by the Office of Independent Counsel in Re Madison Guaranty Savings and Loan Association HATI Trust Digital Library, Universities of Michigan and Purdue.

- 1946 births

- 2022 deaths

- Alliance Defending Freedom people

- American prosecutors

- Arkansas Democrats

- Arkansas Republicans

- Baylor University faculty

- Brown University alumni

- Duke University School of Law alumni

- Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Harding University alumni

- Impeachment of Bill Clinton

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

- People associated with Kirkland & Ellis

- Law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Deans of law schools in the United States

- Lawyers from Washington, D.C.

- Clinton–Lewinsky scandal

- People associated with Gibson Dunn

- People from Leon County, Texas

- People from Vernon, Texas

- Pepperdine University faculty

- Presidents of Baylor University

- Special prosecutors

- Texas Republicans

- Time Person of the Year

- United States court of appeals judges appointed by Ronald Reagan

- Solicitors general of the United States

- Whitewater controversy

- Members of the defense counsel for the first impeachment trial of Donald Trump

- Donald Trump attorneys