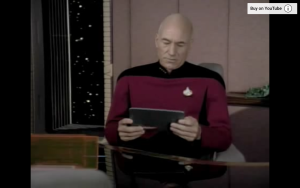

One interesting characteristic of Star Trek: The Next Generation—one that separated it from the original series and most of the early films—was its widespread use of smooth, flat, touch-based control panels throughout the Enterprise-D. This touch interface was also used for numerous portable devices known as PADDs, or Personal Access Display Devices. These mobile computing terminals bear a striking resemblance to Apple's iPad—a mobile computing device largely defined by its smooth, flat touchscreen interface.

To understand the thinking that led to the design of the Star Trek PADD, we spoke to some of the people involved in production of ST:TNG (as well as other Star Trek TV series and films), including Michael Okuda, Denise Okuda, and Doug Drexler. All three were involved in various aspects of production art for Star Trek properties, including graphic design, set design, prop design, visual effects, art direction, and more. We also discussed their impressions of the iPad and how eerily similar it is to their vision of 24th century technology, how science fiction often influences technology, and what they believe is the future of human-machine interaction.

From "electronic clipboard" to PADD

The Star Trek films, beginning with 1979's Star Trek: The Motion Picture, had sizable budgets for set design, props, and special effects. However, the original Star Trek series from the 1960s didn't have the resources to fill starships with buttons, knobs, and video displays.

According to Michael Okuda, original Star Trek art director Matt Jefferies had practically no budget. "He had to invent an inexpensive, but believable solution," he told Ars. "The spacecraft of the day, such as the Gemini capsules, were jammed full of toggle switches and gauges. If he had had the money to buy those things, the Enterprise would have looked a lot like that."

Because Jefferies was forced by budget restraints to be creative, however, the original Enterprise bridge was relatively sparse and simplistic. "Because he did such a brilliant job visualizing it, I think the original Star Trek still holds up today reasonably well," Okuda said.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...