Which do internet users hate more: spam or Captchas? Spam, in email or on blogs (as content or comment), riles almost everyone; but Captchas — those little text puzzles that ask you to decode distorted numbers, letters or words — are at best annoying and at worst ineffective at keeping spambots out.

Each takes about 10 seconds to complete, and with millions being solved every day, that's a lot of time that could be spent doing something more useful.

Realising this, Luis van Ahn, professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon and the inventor of the Captcha (it stands for Completely Automated Public Turing Test To Tell Computer and Humans Apart), rethought the puzzle and came up with reCaptcha, which is more user-friendly, harder for spammers to crack — and helps to digitise text at the same time.

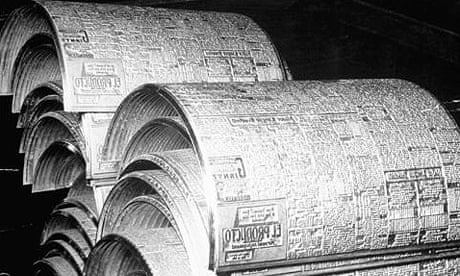

The text needing digitisation is plentiful. Both the Internet Archive and the New York Times are scanning their archives using optical character recognition (OCR). But the accuracy of OCR declines with older material, so about 20% of words aren't recognised. This used to mean humans had to correct the text, which is slow and expensive. ReCaptcha does the job, still using humans, but faster and more cheaply; it takes words unrecognised by the OCR software and offers those to be solved.

Crack addicts

Most Captcha programs apply mathematical transformations to their images which can potentially be reversed, thus allowing spammers to crack the Captcha. Indeed, in February, Websense Security Labs reported that Google Mail's Captcha had been broken by spammers who were able to automate signup. This came not long after claims of cracks of the Captchas for Microsoft Windows Live Mail and Yahoo Mail.

ReCaptcha, however, has two other types of distortion: natural changes introduced by old print fading over time, and "noise" from the scanning process. Along with the mathematical transformations, this creates an image that is easy for humans to recognise, yet delightfully difficult for computers to crack.

Among the sites using it is Last.fm, the music social network. Russ Garrett, a system architect there, says spam started to become a problem about 18 months ago. Fake users would sign up and start spamming members with private messages. "We weren't actually using anything at all before reCaptcha, because we like to keep the signup procedure fairly minimal," he says. "We were considering implementing our own Captcha, but then you end up in an arms race with the spammers where they are always improving their technology and you have to counter them. It was easier to use reCaptcha."

Garrett says that using print to source the images helps make the system more secure. "The advantage is that they've tried to digitise the books using OCR first, so it tends to use words which have been proven to be hard for computers to read. That's useful from a security point of view." The system is simple enough. A site that uses reCaptcha to verify that you're a human, rather than a bot, shows two scanned words: a known "control" word and an unidentified word in its scanned form. The confirmation step is to type them. If the response gives the known word correctly, the system assumes that the unknown word was correct too.

Now the reCaptcha system updates its records. The same unknown word will be served to different sites. Once a word has been recognised enough times - two humans plus the OCR's guess is the minimum - the archive is updated and the previously unknown word, still in its scanned form, is added to the control list. In practice, two-thirds of unknown words are recognised after just two human inputs; only 4% require more than five.

By combining OCR with reCaptcha, van Ahn has increased the accuracy of the digitisation process to 99.1%, meeting the transcription gold standard of 99% (which is based on two professionals independently transcribing the text and then comparing versions to find discrepancies). That compares very favourably with OCR's 83.5%. And reCaptcha is making good progress in digitising the New York Times archives, a project begun only in July this year.

"The New York Times archives start in 1851 [and go up] to around 1980," says van Ahn, "because that's when they started writing it with a computer. We're going to be fully done transcribing the whole thing next year. It's great to be able to tell people that the New York Times archive is going to be fully searchable and accessible on the web pretty soon because of this."

Unpopular but effective

More than 70,000 websites serve 25m reCaptcha images per day, getting 4m words "translated". The number of spambots attempting to defeat the system accounts for the missing success. Over the course of the project, reCaptcha has recognised close to 2bn words , equivalent to 3,405 copies of War and Peace. And despite the fact that Captchas are unpopular with some people, their use is increasing.

"Nobody likes to have a Captcha on their site," says van Ahn. "It does annoy their users, but no websites are getting rid of Captchas." Because reCaptcha uses whole words, and humans read by matching the pattern of a word rather than decoding it letter by letter as computers do, it's generally easy for people to recognise the distorted images. "96% of reCaptchas are successfully solved by the user," says van Ahn. "That is quite good because you have about a 5% chance of committing a typo when you're just writing."

This has made reCaptcha popular with some bloggers. Gia Milinovich (giagia.co.uk) has been blogging since 2002, and has used many different Captchas to keep spam out. She says: "I changed to reCaptcha about a year ago, mainly because I loved the idea of it being useful for something. But it actually works better than any other Captcha I've ever used."

The usability and accessibility of reCaptcha — it has an audio version for the visually impaired — has attracted many websites. Facebook, Twitter, StumbleUpon and Last.fm are among those using it as part of their signup process.

But even if a spammer does break reCaptcha, van Ahn says that it will take them about two hours to "tweak the distortions" and put the spammers back to square one. He and his team aren't resting on their laurels. But: "we have a guy whose sole job is to continually try to break reCaptcha," he says. "He's a very frustrated man."