The Thermodynamics of Local Foods

Posted by Jason Bradford on September 16, 2009 - 10:33am

"No phosphorus, no thought."

Frederick Soddy

Books, blogs, and articles about local foods have been popping up with high frequency recently. I am not going to get into who’s involved or even what they are discussing in any detail, but instead refer readers here, here, and here for background. Or if you want to stick to The Oil Drum, similar discussions occurred here a couple years ago.

I am going to make an argument I don’t see much. Reading the pros and cons on this subject is a bit like watching a pea roll around on a plate. My goal is to stick a fork in that pea and focus on something very fundamental. The point I will make is that one can say with high confidence bordering on certainty that only a predominantly local food system will ever be sustainable.

What I mean by sustainable is the ability to endure. Quite simply and irrefutably I conclude that the current globalized food system is a flash in the frying pan because it doesn’t respect the first law of thermodynamics. Whatever other argument you might want to make against the global and for the local (and several legitimate ones come to mind) this fatal flaw is insurmountable. No quibbles, qualification or value judgments need to get in the way of this basic fact.

The Linearity Problem

The first law of thermodynamics is that matter and energy are never created nor destroyed, they only change form. The forms of matter and energy in the human body come from food, which primarily comes from soils. When plants and fungi occupy soil and grow, they ingest atoms in simple or mineralized forms and incorporate them into organic forms. This process essentially mines soils at an atomic scale.

The concentration of people into urban centers requires shipment of food far away from agricultural lands. Soils, therefore, are constantly depleted of nutrients. Currently, these nutrients are replaced by adding soil amendments and fertilizers that themselves derive from mining operations. In the same way that oil fields deplete, so do the mines that support current agricultural practices, whether based on man-made chemicals or imported organics, such as bat guano from Chile. In essence, the food system is predominantly a linear chain from mine to soil to food to plate to bodies and excretions to the treatment plants to the water ways and land fills and to the oceans.

Fig. 1. The linear flow of minerals from mines to farms and then dense human settlements leads to depletion at one end, and the concentration of wastes or dispersion into water at the other. Graphic from Folke Günther.

Because we can’t create matter out of thin air to replace these depleting resources (First Law) the system is unsustainable. To make it potentially sustainable we’d have to take the waste outputs and make them inputs again to yield a cyclical food system.

Transportation Constraints

A sustainable system must be primarily local because of energetic and logistical constraints. What is removed from a plot of land needs to be returned. Okay, not the exact atoms, but roughly the same kinds atoms in the original quantities and proportions.

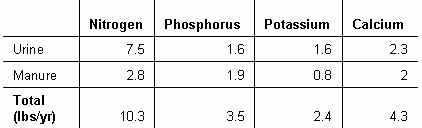

This line of thinking has led me to a very important question: What is the average mineral composition of human urine and feces? My search has not been exhaustive, but I did come across two fairly recent publications that both reference a 1956 study by the World Health Organization. One of these, The Humanure Handbook is available online or in many bookstores. The other is a booklet published by Ecology Action titled affirmatively, “Future Fertility: Transforming Human Waste in Human Wealth.” Here’s a table from those sources, which are really one.

Table. 1. Mineral composition of human waste in pounds per year.

A classic composting method is to combine animal manure and urine with mature crop residues, usually straw. When mixed appropriately, this combination has an ideal ratio of carbon to nitrogen (C:N) leading to the formation of quality finished compost. Straw also includes various transformed soil nutrients, so the final product is nearly a perfectly balanced source of soil replenishment, which is what you’d expect given the First Law.

Let’s put our mind in the toilet for a moment. What is going to be the best strategy for taking the contents of that porcelain bowl and mixing them with straw? Should the straw be brought to every home? Should it go to the municipal treatment plant? Or perhaps the straw should stay on the farm with the “precious cargo” shipped from city to country?

Fig. 2. Some of Fido's best ideas arise during moments like this. Right now he is thinking about all the plastic baggies that pick up his "deposits" in the neighborhood. Shouldn't that stuff get back to the farm, somehow? Would life be better as a country dog?

Folke Günther

These questions may amuse and be largely ignored, but they are completely fundamental. One of the few people I know of who studies this issue is the systems ecologist, Folke Günther. His website provides more up to date calculations for human waste, and he even uses the metric system!

To simplify the subject a bit, he focuses on phosphorus. The reasoning is straightforward--it is ten times more concentrated in the human body than in the Earth’s crust and therefore the most limiting nutrient in most locations. Essentially, if phosphorus can be reclaimed effectively so can everything else.

Fig. 3. Günther’s model of the phosphorus cycle in a balanced agricultural system with exports of food being returned to the land in the form of processed human waste.

In Günther’s writings and presentations on the requirements for sustainable cycling of nutrients, he suggests that the population of rural areas needs to be about twelve times larger than urban areas. He gives a scenario where ruralisation occurs in a region over 50 years based on the normal turnover rate of infrastructure—essentially as urban centers decay they are not rebuilt and investments in housing and other infrastructure are made instead in the adjacent hinterlands. Furthermore, assuming a rise in transportation costs, he also shows that a rural economy based on local food and energy weathers oil depletion well, in contrast to a city that must import basic needs.

I find these concepts obvious. I think a child can understand the basic premise operating here: If you take and don’t give back, it runs out. The implications, on the other hand, are stunning. Will the migration to the cities, a demographic phenomenon that has gone on for so many decades, be necessarily reversed in the 21st century? If so, is it even remotely possible that this might happen in a thoughtful way as envisioned by Günther? And of course ruralisation in a region like Las Vegas is impossible.

Historic Model: China and Village Ecosystems

This topic has not gone unexplored on The Oil Drum. Phil Harris described the essentially local and long-term persistence of agrarian village ecosystems, especially in China. I have heard stories about farmers in China competing for humanure by building comfortable and decorative outhouses along roadside borders of their land. Please send pictures of these if you come across any of them. I am looking for some design ideas for the future.

"The human mind...burns by the power of a leaf."

Loren Eisley

What is the average mineral composition of human urine and feces? My search has not been exhaustive.

I do not know whether a pun was intended but it did make me laugh.

Sawdust or grass clippings could be substituted for straw, as is mentioned in the Humanure Handbook. I use 'enriched' straw harvested from our sheep barn every spring in the garden, and the results are impressive.

dry leaves work well for those of us in areas with deciduous forests.

I have about three years of experience composting the last thing most people think to compost, using Jenkins' method pretty closely. (Except for getting the contents of the buckets into the compost bin, there's very little to object to.) Combined with the output of a tiny flock of urban ducks and a lot of coffee grounds from the local caffeine pushers, I've turned out about a dozen cubic yards of compost. It ain't hard.

Using Jenkins' method, sawdust is great for use in the bucket, but dried and crushed leaves, shredded paper, or chopped straw work nearly as well. After a few days of sun, it is relatively easy to gather leaves and bust them up on a parking pad or piece of plywood, in a big bucket, with a (reel) lawnmower, or even by hand. Chopping straw isn't easy to do without a hammer-mill. If your yard gets covered with leaves each fall, they're probably the best option.

Whatever your cover material, moisture is the key. Dry cover material yields stink and a strained marriage. Moist (as opposed to wet) cover material is amazingly effective at eliminating any objectionable odours.

Grass clippings, at least the ones from your average North American lawn, don't work well in the bucket or in the compost bin. Even on their own, they contain too much nitrogen and, without careful management, will make for some pretty strong ammonia fumes around the compost bin. My conclusion has been that grass clippings are best left where they fall while mowing.

Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) & "Buffalo" (I hate refering to Bison as "buffalo") grass (Buchloe dactyloides) make a fine lawn or pasture mix. Their dried clippings are excellent for mixing with human shit in the bucket, to be transferred to the compost heap.

It's hard to fault this reasoning -- except that clever humans have found ways to convince themselves that the laws of thermodynamics don't really apply to them, or at least, not now. As long as mineable phosphorus remains (not forever-- the Nauru story is instructive here) and some form of cheap transportation exists, then food can come from all over and centralized corporations will be able to arbitrage labor costs around the world.

I deal with these issues on a nearly daily basis at my local food Co-op, which I try to push in the direction of encouraging local producers by buying their produce. But the national distributors are "cheaper" and "more reliable" -- and anyway, "we" are "competing" with Safeway, Kroger, Wal-Mart, Trader Joe's and the like. Arggh! It's just impossible. Human stupidity is far more profound than human brilliance, and the overall sum is bound to be less than zero.

Never,

Believe me the problem looks even worse from the pov of a small farmer-your employment opportunities are probably less limited!

The article lays it out in terms that are not open to much argument insofar as the technical facts are concerned.

Personally my guess is that it will be a LOT EASIER -but still very hard-to leave the city dwellers where they are and capture and concentrate the waste nutrient stream and transport it back to the farms for quite some time.

It also seems to me that it will be easier and probably cheaper to continue to grow staples such as wgeat ,soy,corn,rice more or less the way we do now for quite a while -at least for about as long as it is possible to continue to supply the huge amounts of energy to run essential city systems such as water/sewer/lights/ heat /distribution ,etc.

So maybe we have some breatheing space-but not a whole lot.

The technical aspects-daunting as they are- of solving the food and energy crisis in my opinion are pretty small potatos compared to the political and bau aspects-I don't think the public will go along until either literally at either the point of a gun or at the point of starvation.

But unless there is some huge positive Black Swan in our future I expect that Mr Bradford has made his case.

The time frame seems to be the biggest question mark in his analysis as I see it.

Hi Mac--

On a personal level, you are quite correct. My employment opportunities are essentially limitless because I personally can operate pretty effectively in either a very low tech or very high tech environment-- I have consciously arranged things that way. However, my personal limitations are health and age -- and once again, we are back to the immutable laws of thermodynamics. Very few people have had my opportunities, and way fewer have taken advantage of the opportunities presented. Most people go for the money, not experience or generalized skills. But my skills die with me-- and no one wants my job, so I have no one to pass those skills on to.

Small farmers around here are no different from small farmers anywhere -- they go out of business unless they find some boutique niche, and in any case, it is a really hard life. No wonder they go to work for ConAgra or Kroger! My idea (stupid idea, it seems) is that food Co-ops ("progressive" organizations that put "community" before "profit") could be the nucleus for an increasingly localized, partially self-feeding, locally owned and controlled food network. But it is uphill all the way, and even the people who claim to want to "shop locally" go to Wal-mart because the prices are better. In fact, they drive 50 miles to get there -- gas is so cheap.

I agree that Bradford has made his case for the ultimate concordance of thermodynamical laws and human culture, and with you that the time factor is unknowable, but almost certainly likely to exceed any of our lifespans.

BTW, my wife has become very intrigued with "humanure" and has tried to work out systems here in our small town, following the guidleines and plans from the Humanure Handbook -- but on a practical level it is tough, and just so much easier to flush the toilet.

Your point about co-ops reminds me of a conversation I had yesterday.

I think for every 1 nutcase that spends the extra money or puts in the effort to grow/eat a diet composed mainly of local food, there are 10 who would do it if they really understood the implications of commodity cheapness.

My son's piano teacher, a very progressive woman, and well-educated, was complaining to me that the prices at the farmers' market in Boulder are unaffordable. She is right, by and large. I reminded her that produce from California is often picked by "exploited" agricultural workers (we now have the movie Food, Inc, that has made this observation seep into the mainstream consciousness). I also pointed out that nutritive value is not equivalent, between produce grown by small local farms and that sold at King Soopers. She knows this, and cares, and understands, and though she may not eat all her food from the farmers' market, she may buy some a little more joyfully in the future. Besides, both of us are a little overweight, so we can joke about this being a diet strategy: to pay the same, get more nutrients and fewer calories.

By the way, I have been paying for piano lessons using "farmers' market bucks" (cash equivalents that work only at the market in Boulder) - just because I am usually short on real cash - using them effectively as a local currency!

What you write about fighting to get local food into the co-op is disheartening. I am wondering whether a clear "mission statement" for the co-op - where it may have to split into two different organizations, because some people remember co-ops as a way to save money on food through putting in some volunteer work - could take some of the frustration out of the situation.

Reminds me of this quote by Wendell Berry:

"We thought we were getting something for nothing, but we were getting nothing for everything".

Paranoid,

I find myself more and more interested in your pov and the info you bring to our attention.

Do you have a blog of your own?

In the immediate term we can feel full, nourished, and energized more than we can feel nourished . It takes weeks and months, and probably some very hefty hospital bills before we realize we are actually malnourished. Feeling full does not mean we have satisfied our bodies requirements.

This is another fundamental flaw in our thinking that the piano teacher might also be forgetting. The idea that food should be cheap is laughable. If it's not expensive then someone is not being paid a fair price to produce it or forage for it. If she wants food to be cheap (in dollars) then she should grow it. Maybe then, when people like her realize how much knowledge and work is required to efficiently produce this fundamental necessity to life, we won't complain about how much real food actually costs.

Our food system makes quick calories cheap, rewards those that can produce them the fastest, places high prices on food that is good for us and penalizes those who produce it.

Your example is another example of how our basic thinking and perceptions are flawed.

I send 10 dozen eggs per week to the local co-op, and get a fair price, but my small scale agricultural system is not industrial and I must do full time work navigating the imaginary world of perceived sustainability in our land development and "green" building methods. So rather than putting more food in my neighbor's stomach, I have to support a fantasy industry that will actually pay the bills. Paying your local up and coming small scale farmer/engineer/banker/biologist/whatever to transition to producing good food full time is not an overnight effort. It's a three to five year process at best, and if at all.

A very interesting world we live in.

Yes, and I can see how a generation or two of cheap calories (and cheap toys, cheap clothes, cheap transportation) has warped our sense of what is valuable, and what the true cost of something is. In that setting, our "common sense" will tell us that the farmer who charges $6/basket of strawberries, when they are obviously less than a quarter the price at Safeway, must be trying to get rich at the expense of Boulder food snobs.

We constantly need to be reminded, through growing some of our own food, through really getting to know one or two farmers, through being thoroughly familiar with statistics about farm families needing a non-farm income to survive, that farmers' market prices are somewhere between fair and a little dicey (too low!).

My blog is http://www.ecoyear.net. Thanks for the kind words OFM.

Or perhaps our common sense will be telling us something less histrionic, that maybe it's not really worth paying four times as much for strawberries that are only a little better...

That right there is the problem.

What is the true cost of strawberries?

Factory farmed with slave labor costs less in dollars. No question.

I mentioned the "taking advantage" angle because that was what I was hearing from our music teacher. She specifically said: "Why are they charging so much? Haven't we removed the middleman?"

As to how much strawberries are "worth", that all depends what you are getting, how it affects your health, pleasure, and well-being.

Simply put, there is more flavor in one $6/pint strawberry (the size of a marble - a small marble), than in 5 large, walnut-sized, $1.50/pint Safeway strawberries. Whenever I've made the mistake of buying grocery store strawberries (Whole Foods is hit and miss in that regard), I've considered spitting them out.

At this point, I am suspecting that flavor is the best proxy we have for "quality", defined in human body terms (not shelf life, you know...) If anyone knows how this might be done, I have considered paying for nutritional analysis (if cost is at all reasonable).

Also, in the "cost", we have to factor in yield, shelf life and other transportability issues, ease of picking, ease of growing, water cost to the environment, how much you pay the workers and what conditions you set up for them, and I'm sure I have left some out. These are minimized at the expense of the nutritional value of the fruit.

Now to tie back to the post, imagine factoring in something like long-term sustainability, whether, like toxic dumps, food grown without attention to sustainability represents an insult to the Earth we are entirely dependent on. Can you open your refrigerator and point to the items that have enhanced the place they came from?

Here's a thought from Gary Paul Nabhan:

W/r/t Quality p. taste is a determiner of quality. Have you ever tasted sweet celery?

Quality produce dehydrates. Chemical fertilizer grown produce rots, and doesn't keep as long.

Brix is the measure of sweetness that Carey Reams the agronomist discovered applied to any fruit or vegetable that you could extract some juice. He discovered the positive co-relation between brix (sweetness) and nutritional density by doing assays. Furthermore he contributed the fact that one of the main keys to getting that better taste was determined by how phosphorous was working in the soil. 95% of all nutrients have to enter the plant in phosphate form.

Commercial phosphorous or the middle number on the bag of fertilizer is derived from taking apatite rock and soaking it in sulfuric acid. According to Dan Skow (Intl Ag labs -and highbrixgardens.com )this gives the plant an energy release but in fact kills off microbes in the soil that are required in order to make phosphorous bio-available to the plants and the fungal organisms necessary to produce quality.

You can buy refractometers for about $75. and score your produce against a high brix scale.

I have tasted high brix celery and I can't go back :(

Imagine being a chef and knowing the superior brix of the vegetables and fruit that you were serving!

I believe that were we to find the right diet and to make that diet of superior nutritional quality that we would find that we haven't been living. As is stated in so many words by Franco Caveleri author of "Potential Within" he is a nutritional biochemist.

P. (I shortened it -just to scare you :)) I think you would find the organic consumers association fight with Whole Foods interesting

http://salsa.democracyinaction.org/o/642/campaign.jsp?campaign_KEY=27761

Never saw anything about Brix before. Google turns up more noise than signal unfortunately, sites that do have information aren't very comprehensive. Do you have any further sources of info?

A downside to produce is that it isn't very calorie dense without drenching it with oils or sugars, would produce higher on the Brix scale have more calories?

If you go to www.acresusa.com. You can source copies (cd's) of acres conference presenters. Dan Skow (who I referenced routinely presents production information on how to increase brix)

There are others (whose names escape me at the moment promoting high brix foods. Try searching on Dr. Reams)who are keenly pursuing higher brix but they seem to be mostly producers. I guess the public just hasn't learned that there is such a thing as quality produce (those that know of it probably take it for granted) and if you don't know about it then you probably haven't had it. Like that celery I mentioned. I have met many men that have told me that they don't like vegetables. I'd be willing to bet that they've never had high brix produce.

Dan Skow talks about being able to finally source some quality peaches. Not those things that are hard and then are ripe for about 2 hours and then go bad. (They are sold out before you can say: 'boo')

He has a sheet that lists the brix scores that can be attained. So you can compare what celery with a brix of 3 versus 0 (which is what the stuff at the store scores)tastes like.

I've never had high brix turnips, I'm working on the principle that I might like turnips, just that I have yet to try them.

I predict that what will surpass local, organic food and form the next food movement is: local, organic and high brix food. Though it could do perhaps with a better name. I know, how about: 'real food'

When organic produce tastes way better like p.'s strawberries -that is higher brix. It turns out that phosphorous works better in a organic model. This increases the calcium in the plant replacing the potassium. This greatly increases shelf life.

If t.s.h.t.f. and we all had root cellars but weren't growing our own organic food. And for arguments sake the stores had ample food so that we all could stock up the cellars. We would be surely disappointed to find that it would all rot within a month.

Thanks. There appears to be a good bit of mumbo jumbo from various online sources wrt to brix, but I think there's something to it. I've noticed at http://www.nutritiondata.com big differences between the calorie content of say kale and cabbage, but they are from the same plant just a few centuries back. Considering only the non-water portions of the plants, the calorie content is about the same, and one site I saw at a University suggested an inverse relationship between the water content and the brix scale. As for higher brix produce being disease resistant, a couple of studies claim secondary metabolites are higher for organic produce (they serve the purpose of making the plant undesirable for pests). Hobbyists on various forums report a high brix value for their organically grown stuff.

As for strawberries, raise some wild ones, taste is incredible. There is a reason novelty restaurants pay $25 a pound for them. Small and delicate though, rarely larger than a marble. Not to be confused with a related invasive weed from India with a yellow blossom and nearly identical foilage.

Good day!

One story that Mr. Skow reports (if memory serves) was of a farmer standing in his corn field talking to his neighbor who was standing in his field of corn. While talking the one neighbor who was doing things organically versus the neighbor who wasn't.

What they observed was that the grasshoppers were all over in the one field so many that they were landing on the farmer. When he crossed into the other neighbors field they left. Why? Grasshoppers don't have livers. If they ate the high brix corn they would die.

Brix is not like adding sugar. It is a reflection of increased sweetness conveyed by increased minerals in the plant or fruit.

So our mouths can tell us what tastes good and what is good for us. Sweet eh?

It doesn't seem to always be the minerals, here is some info from Kentucky State University. Kale at day 0 from Farm A has a brix value more than twice that of produce from Farm B, yet the ash content is slightly lower for Farm A.

Thanks for the link. Barrett I'm not trying to be difficult but I would reject the results of that study as telling me anything relevant. (What actually do you think it tells us?)

I know several facts. 1. High brix food tastes better. 2. It has been assayed by others (Carey Reams) showing higher levels of nutrients (Do we need more scientific data? I'm satisfied). 3. Nutrients and proteins are best derived from high organic matter levels (5%+)from balanced minerals (high c.e.c.) and amino acids in the soil.

The test doesn't compare apples with apples, it doesn't test organic versus conventional. And ash values for our purposes are useless. Sugars (as I understand)don't leave ash values (toxic heavy metals would). This study might best tell us what foods to avoid. Increased brix is not achieved by spraying molasses on to plants. On the surface the study appears to be an attempt to find a cheap way of getting increased brix. The lesson of our time is that we are getting what we pay for and we are reaping what we have sown.

I guess the answer to the question I posed above is no, you have never tried sweet celery.

Perhaps you will find this instructive:

Charles Walters wrote a very good book called the Eco-Farm, he says this:"The summary stacks up like any college syllogism. NPK formulas as legislated (and enforced by state departments of agriculture) mean malnutrition, insect, bacterial and fungal attack, toxic rescue chemistry, weed takeover, crop loss in dry weather, and general loss of mental acuity--plus degenerative metabolic disease--among the population, all when people use thus fertilized and protected food crops. Therefore the answer to pest crop destroyers is sound fertility management in terms of exchange capacity, pH modification, and scientific farming principles that USDA, Extension and Land Grant colleges have refused to teach ever since the great discovery was made that fossil fuel companies have land grant money."

Edit:

I'm having a hard time locating his numbers. Presumably his assays produced datapoints like IU of beta carotene, mg of tryptophan, mg of ascorbic acid, etcetera. Lots of sites out there are repeating the assertion that his assays showed higher levels of nutrients, none that I've found yet are showing his numbers. That would make the answer to the question "Do we need more scientific data" a yes.

When you bake something at 550 deg C for 48 hours its the P, K, Ca and trace minerals that are left behind as ash. Ash content is correlated with the mineral content of the living plant/vegetable. Heavy metals even at toxic levels are a negligible fraction of the ash. What the experiment shows is that higher brix value does not necessarily mean higher mineral content. Other non-mineral based nutrients like vitamins and antioxidants may be guaranteed to be higher if the brix is higher, but their experiment demonstrates that it is definitely not always the case with minerals.

All in all it seems a worthy pursuit for a gardener to measure brix values. I haven't tasted high brix celery, but would like too.

Never saw anything about Brix before

I know I've mentioned Brix here more than once.

I usually point to journey to forever

http://www.journeytoforever.org/garden_organic.html

as a starting point.

A downside....would produce higher on the Brix scale have more calories?

How is that a downside? Ever try to get ehough food calories from eating just raw veggies - no seeds?

I'll replace the "...." with the original text and it should be clear.

"A downside to produce is that it isn't very calorie dense without drenching it with oils or sugars, would produce higher on the Brix scale have more calories?"

It's difficult to get your whole calorie budget with produce because it doesn't have many calories is what I was saying.

And here in lies the problem. Our nature seems to be to determine how long we've got before we really have to adapt or change direction. We fail to make the connection that the longer we delay the more energy it will take to regenerate/repair what is damaged. How long we've got is not important. The majority of us agree we are not respecting the basic law that Jason has indicated. In fact discussing it leads to making the problem worse, because the discussion detracts from the real work to be done.

Instead of asking 'how long?' we need to change our basic values, and then ask 'how can we place these elements in relation to each other to minimize energy losses and increase the health and productivity of the system?'

I think the proof that will determine whether this civilization can earn the privilege to continue (whether for another year or a hundred), will be if we can change our human nature to avoid procrastination regardless of the perceived sacrifice, and instead get to work in a proactive way on the order of decades instead of tomorrow or next week.

Part of the problem as I see it is that we can no more change our human nature than a fish can decide to breathe air. Since that is not in the cards what it seems to me that we might do instead is use the knowledge that we already posses about our nature and subvert it for our own benefit and survival.

We have become quite successful for example in using technology to manipulate the desires of the masses of consumers to keep them buying things they hardly need.

I think first we need to define very clearly what our basic values need to be in the new paradigm.

Of course therein may lie the rub, how do we arrive at that metric?

Assuming we can do that and once it is done we then need to roll up our sleeves and relentlessly "Market" those new values to the population at large.

People from the old paradigm need to be ostracized and given as little chance as possible to remain comfortable in it.

In simplistic terms, we must find a way, to make the normal instinct to seek power and status compatible with preserving the commons. Perhaps the image of the CEO of the company on a bicycle needs to be portrayed and heavily marketed as much more desirable and sexy than that of a CEO in a luxury sedan.

I think we may already have the knowledge and the tools to start changing from BAU to a new order.

The question is will we do it, or are we cursed by our very nature to wait until it is too late?

Tell that to my Senegalese bichir, or my ornate bichir, or my 110 cm Lepidosiren lungfish, or my Protopterus annectens lungfish, or any of my neotropical catfishes that gulp air & extract O2 from their gas bladder, or loricariid catfish that swallow air & exchange gasses thru a highly vascularized portion of the gut! Many fishes breathe air, especially those from warm tropical freshwaters that become hypoxic during the day.

Yo DD, I assume your reply is tongue in cheek, yes?

I happen to be somewhat familiar with biological evolution theory in general and Ichtyology is something I have long had a personal interest in.

When you find me a member of say, the ole Condrichtyes clan, that suddenly looks over at his bretheren cruising the local reef and DECIDES to go catch some rays, (forgive the pun) up on the beach with the gulls, You let me know, OK, brother!

Well, yes & no. I wanted to provide a little humor but I also did want to point out that there are a lot of air breathing fish. You're right tho, I can't think of any air gulping chondrichthyans.

As for "deciding," I dunno. When the bichir lurking at the bottom of the aquarium suddenly darts up for a gulp of air (which it must do periodically or it will drown), is it simply responding automatically to reduced intravascular pO2 stimulating receptors on neurons in its brainstem? Or does it feel hypoxic and accordingly decides to go up for a gulp? Wish I knew.

Tell you what, try this experiment on your self, take a few deep breaths then hold it. see if you can decide not to breathe. I used to teach a dive physiology course for skin divers and though I'm not going to get into it here I can assure you that there is *NO* decision making past a certain point when it comes to breathing for humans. I'm going to make a wild guess, because I'm not up to speed on the physiology of sarcopterygiians, but I'll bet they are not making decisions either.

For humans, when the breathing reflex kicks in, and you happen to be under water you will breathe water whether you decide to or not. BTW in humans it is the increase in PCO2 that triggers the breathing reflex the level of O2 can fall dangerously low before the level of CO2 rises sufficiently to trigger the need to breathe Google shallow water blackout,...Just sayin :-)

If a diver tries to extend their underwater time by hyperventilating, they'll lower their CO2 level. Will they raise their O2 level at all, or are they just hurting themselves by fooling the breathing reflex?

I hear you FMagyar. I'm a PADI certified diver and during my training we were doing the buddy share breathing thing in a swimming pool & when I felt hypoxic I hit the surface without even thinking about it. Just happened, & was embarrassing. So sometimes I decide to breathe & sometimes I don't. But I'm not privy to the cognitive process of any critter besides myself. I don't, and can't, know what anyone or anything else besides myself is thinking, or even if they are thinking. So I'm not going to bet on whether or not a fish makes a conscious decision to breathe. I simply don't know.

Btw, polypterids (bichirs & the reed or rope fish) aren't sarcopterygians. They breathe air like a sarcopterygian and they have bones in their pectoral fin lobes like a sarcopterygian (altho the bones aren't homologous) yet they aren't even remotely related. Conventional taxonomy places them as the sister group to all other actinopterygians but this is only done for convenience. Truth is, they aren't actinopterygians either. What are they then? No one knows. Their fossil record only goes back about a million years. They must have split from the common ancestor of sarcopterygians & actinopterygians in the Devonian, and we'd need fossil evidence from that far back in time to know what they truly are. They are truly "living fossils," that's for sure, and are the coolest fish, in my opinion. They truly deserve equal taxonomic status with sarcopterygians & actinopterygians; they are the third fundamental type of bony fish.

I have a koi pond and when it gets Texas hot here in the summer they suck air off the top............so I guess you are right.

The temp has dropped now and they just swim around normal which makes me feel better.

"my guess is that it will be a LOT EASIER -but still very hard-to leave the city dwellers where they are and capture and concentrate the waste nutrient stream and transport it back to the farms for quite some time."

See below under "articles on sludge". It looks like there are serious health challenges to using this stuff safely on a large scale now. What we settle for remains to be seen.

But have we tried very hard?

Sludge is just what we happen to end up with after waste treatment, right? Have we really tried very hard to separate it into it's constituents, like Phosphorus?

It depends. Austin Texas has clean enough shit to sell their sludge for gardening.

Alan

My local co-op (conveniently located across the street from my home) has a program called Local Six, meaning a six county region they define as local. http://www.firstalt.coop/1_Local6.html

I am talking to them now about growing for this program and soliciting info about what they currently buy, for how much, and what they'd be willing to pay to support a local farm. It takes a lot of work to establish these relationships, ramp up local capacity and knowledge and develop an educated population of eaters.

Commodity grains and legumes are absurdly cheap. But by selling direct to the consumer or retailers a shorter chain of possession and distribution results, which means the farmgate income is higher while still bringing a reasonable price at the checkout counter.

If you or anyone else can figure out a way to instill a sense of OWNERSHIP and therefore loyalty to local coops it would boost thier growth considerably-and I do not doubt that if food dollars become scarce coops can provide food cheaper than the current system-but not the same food and not in the same variety all the time of course.

We still have a few small markets around here that will buy and sell local produce and they can sell and do sell local apples,casbbage,potatos for much less than the chain stores right in the nieghborhood charge for shipped produce.

But hardly anyone shifts thier buying habits to take advantage of the bounty.The sale of apples does not go up much.

Some of the older women will buy a quantity and slice and freeze some and put the rest in the fridge and eat more apples for the next month.

But you can stand in line behind some obviously not so propperous woman who is very poorly dressed and who drove up in a very ratty old car and she will tell you how HER Momma used to buy in bulk and put up food-and she will buy a five pound bag of potatos for twice the per pound price of the fifty pound bag.

Now even if she can't afford the fifty pounds(and she can ,judging from the processed junk in her cart most times) she could divide the bag with her nieghbors or adult kids.

The local food movement has a LONG WAY to go.

Even mill hands and folks on unemployment don't seem to be in enough of a bind to really watch thier food dollars if watching requires a little thinking and planning.

You are SO right!

So, what motivates the locavores I know?

I think the issue of "health" is the most powerful motivator I have seen so far. A couple of bloggers come to mind (http://lovelandlocal.blogspot.com and http://transitioncolorado.ning.com/profiles/blog/list?user=3bq3kofvpse5i). These folks (Lynnet and Nisa) are activists, and the trouble they go to in order to eat local food (sourcing, growing, preserving) is their political action. I'll include myself in there as well.

What might motivate less "activist" types?

Convenience (CSA: your shopping is essentially done for you);

Community - picking apples and making applesauce as an activity to do with friends, as opposed to going hiking, for example.

Quality of food for kids - linking local farmers with schools - this is subject to price, but seems more do-able than asking people to give up a vacation, new car, or updated wardrobe in order to eat local turnips and carrots, instead of far-flung pasta.

Charity - having a church buy food from a local farmer and prepare it for households in need

Food snobbery - the Slow Food chapters seem to oscillate between haute cuisine and local heritage old-timey values

I am looking forward to reading the new book on the topic from the Transition Town folks (http://transitionculture.org/shop/local-food-how-to-make-it-happen-in-yo...)

Which makes me think, if a "locavore" is a person who favors local food, what shall we call someone who prefers to eat food grown on, well, closed loop systems? A "scatovore"?

Food snobbery is a massive motivator for local eating in California, especially among the affluent.

I agree with you about food dollars. If you avoid the processed food isles at the natural food coop, where prices are exorbitant, and stick to the fresh fruits and vegetables, whole and minimally processed grains and legumes, fresh dairy and local meats, you can eat very well for not a whole lotta money, even with a lot of organic products in that mix.

I think the average family in the US spends 10% of their income on food, but about half of this is eating out and most is highly processed. So, it may seem like only wealthy foodies can afford this but I really don't believe that is the case. Knowing how to cook and store whole foods, avoid addictive processed, convenience foods is probably a major limiting factor right now.

I think if we put our mind to a transition from processed food back to wholesome ingredients, we could do it and it would seem acceptable, even life-affirming, full of creativity and joy. After all, people waste time on stuff they don't much care for.

However, people's lives seem almost set in stone. The stress level is too high to stop watching T.V. That leaves no time to cook and clean after a meal. The kids won't sit down and are picky as hell, so each prefers to microwave their favorite frozen dinner. That all is so amazingly expensive (add to it the cost of medications for blood pressure, sleep issues/depression, and diabetes or pre-diabetes), that both parents (if present) have to work at inconveniently located jobs they dislike. Which fuels stress levels and kids' attitudes.

Unraveling this takes years of determined work. I am still up to my eyeballs in it, trying to demonstrate that a piece of fruit (I mean one of those stupendous Colorado Rosa peaches, or a prized Honeycrisp apple) ought to be as acceptable as a bowl of Life cereal (the kids are 5, 7, 10 years old, but my (pre-diabetic) husband craves cereal the most!)

What I see, is that I have to devote more time to thinking about food than even I do. I think I am facing a more picky family than many other people do. But still, the chicken nugget, the store-bought pizza, the Vitamin Water "treat for doing your homework on time", are conveniences that free me to do some reading and writing (such as here!!), which in turn, keep me on my path.

So, sometimes, I think the only hope will be, painful as it seems, when the commercial processed food is blasted out of existence by high energy prices - or when our budgets demand that we think of a $3 loaf of bread as a luxury, when the flour for it costs a couple of dimes. I guess I'm saying as long as people can afford cake, they are not likely to be baking their own.

Maybe establishing a food snobbery trend is the path of least resistance.

Last year my son was selling produce at the local Farmers' Market. He made a little money, especially on dried herbs. He was planning on selling again this year and so attended the pre-season venders meeting. There was a guy from the state there, telling venders about all the regulations they must adhere to. There was paperwork that venders needed to fill out & submit. Some of the questions were quite intrusive. Live plants couldn't be sold unless one had a nursery permit. Processed foods couldn't be sold unless they were processed in a licensed & inspected kitchen. Selling eggs was risky because if someone contracted Salmonella from them, even if it was their own fault for not cooking the eggs properly, both the vender & the Farmers' Market could be sued. To make a long story short, my son & I decided that selling this year at the Farmers' Market wasn't worth the hassle & risk. Instead, we concluded that paranoia over "biosecurity" had forced the production & sale of local food into the underground economy and if we were going to sell food it would have to be done with the same stealth as tho we were growing & selling marijuana. This is what it's come down to around here.

DD,Your comments today resonate loud and clear with-believe it or not-most of the people on the far right end of the political spectrum.

I have several ecologically and ernvironmentally aware friends,very intelligent people, who believe that the government is a sort of semi alive cancerous organism that will grow until it totally consumes whatever is left of our individual freedoms and privacy if the trend towards cebtralization of money,power and information is not soon reversed..

This is not the time or place for that particular discussion but i want to point out that there is plenty of common ground that we can work together for the good of all of us if we lay off the cheap rhetoric and look for it.

Most of the poor people but proud and self supporting I am acquainted with are conservatives politically in no small pert because the govt is constantly closing off thier opportunities to run small local businesses.

A part time truck garden type farmer cannot comply with all thse regulations-compliance costs more than the business is worth in many cases.

Larger businesses can comply by passing on the costs,which are spread over a larger volume-crying crocodile tears all the time of course,knowing full well that the regs prevent much real competition from developing.

A retired friend who was servicing chainsaws,tillers,and other small machinery at his isolated country home was hauled into court recently for violating zoning and business liscense regulations-almost certainly after compliants were made by the shop on the highway that charges three times as much for work half the quality.

Of course the problem could have been a petty bueracrat who has a little authority and is eager to use it to destroy many decades worth of working community.

The right "wing nuts" have some things to say that truly need to be heard by those interested in community and sustainability.

It is inadvisable to allow oneself to be assigned to "left" or "right." That divide and conquer technique has been used since time immemorial by the ruling class to subjugate the other classes. They pay factions small amounts to fight each other, then walk off with the goodies.

Inadvisable, eh? What do you think you've just done by talking about "the ruling class"?

Ruling class is neither left nor right. They are "top"

They have the means to divide the ruled into left/right, Catholic/protestant, Christian/Muslim, then watch us fight, arm both sides and walk off with the profits.

Yes, inadvisable. I would guess, HFat, that you don't belong to the ruling class.

I do, though. Just a word to the wise.

LOL!

As someone whose personal ancestry leads back to a ruling class currently no longer in power, I can attest to the fact that the wheel, sometimes it turns. So now, from here, at the "Bottom" I musk ask, you don't perchance happen to have a position open for butler or some such on your estate do you? I'd take gardener and in house energy efficiency maintenance expert as well.

Your humble servant,

Cheers!

dd -

It's that way 'most everywhere. But paranoia over biosecurity is not what's behind it - it's paranoia over the market share of big growers like Cargill & ADM and the big retailers like Kroger & Walmart. All that bureaucratic rigamarole is just part of doing business for those outfits; but, as you and your son have discovered, it can - and does - shut down the small players before they can even get started.

As for me, I'd a whole lot rather pay $5 a dozen for eggs from a guy with 25 hens running around in his back yard than pay $1.25 a dozen from some "vertically-integrated" conglomerate with 40,000 hens to each aluminum henhouse and a 3-week transport time. 'Round here, we just keep it to ourselves so that the USDA man never knows to come looking for us. That's just one of the great benefits of being part of a real community.

I know long term we need to line up alternative suppliers for grain, but it's tough short term. Farmers markets and small growers understandably prefer to deal in premium produce rather than cheap commodities. I've decided the next best thing is to purchase from the conglomerates as far down the value-added chain as possible. Bulk (Cargill) flour costs $.28/lb in the warehouse stores. Yeast and sugar are similarly cheap in bulk. The profits they make off those sales are minuscule compared to baked bread and processed food.

I found a mill that sells me 50lb sacks of hard red wheat, and I have begun to grind it - I'm with you. I have about 5 acres planted in grain, with a plan by Spring to have a total of 20 acres in various grains, especially grains that have some short to medium term re-seeding capabilities. While tonight I went out and hand scythed for the first time, I know that "long term" I have to find a way

to harvest potentially of 60 acres of grains without a combine, because the closest place I've seen grain growing is 100 miles away. Someone could do the world a service by creating a micro combine that could be pulled behind an atv/gator/whatever that would be fueled by alcohol or biodiesel.

Ky,

I agree with you to the extent that ONE of the oprimary drivers of this foolishness is "paranoia over the market share of big growers"

But they also have many well meaning and generally well educated professionals on thier side from the public health authorities to the fire department.

The problem is of course that thier educations are incomplete and in reducing one risk to as near zero as possible in defiance of the law of diminishing returns they ignore other risks that are entirely off thier radar for the most part.

Then there are the tens of thousands of "useful idiots"(from Lenin And Stalin's little experiment)who jump in and write editorials and letters to the editors.This sort seems to jump on every convenient bandwagon that passes by in order to make themselves feel good by proclaiming thier dedication to the good of the public.

Since it's bad news that sells ,well,they must find some suited to the forum,regardless of how dubious it may be.We throw tons of perfectly good fruit away every year on our one horse farm alone because these idiots have been telling women (and men more recently ) not to buy it,thier message being essentially that fruit which is not cosmetically perfect is if not actually dangerous at least is not(by implication) as nutritious.

It has been my experience that the average teacher,dietitician, or nurse never reads a book about thier profession once they leave school.Whatever they were taught by a professor perhaps with her own misperceptions or axes to grind is irrevocably fixed as gospel in thier minds.This is not to say that they don't change somewhat as the result of inservice training -but if there IS no in service upon a given topic....

Give me an effing break. Virtually all of them, by the very fact that they are "professionals" is ill-educated and miseducated. Education from the latin root for "lead". Don't follow them. The system and the structure within which they swim is wrong and they will only make things worse.

Nor, as Ward Churchill pointed out in his recent trial, are there any "good intentions". $90k/year for a firefighter here in Gray, ME. Not including the off-the-books pensions and subsequent benefits. And they are out setting up "voluntary" roadblocks for more contributions.

That doesn't fit any definition of "well meaning and well educated" I can think of.

I'm not being cynical. YOU are being suckered.

cfm, the growlery, gray, me

Ditto with this conservative, what you say resonates very strongly. Things appear so tortuous to comply to sell from my farm (bought in semi-retirement) that I decided my best short term scenario is to give it away to the neighbors. It may cost me some $'s and a lot of sweat, but I need the skills, the relationships, and the exercise enough that I don't care. It does mean that that I'm only using a fraction of the land, and going for variety of goods and experiences at what is a too small of scale (moving to 100 eggs/week is

an example) to make MONEY - today. But write a different world scenario, and i can up the scale (with neighbor hands) to make it work economically. Even today, a layed off neighbor, working a part time job asked to borrow 5 acres to do sweet corn to sell by the road,

which i agreed to, maybe the first step in upping the scale.

Is there any talk of "heirloom" wheat strains? It appears that the wheat that is grown on a large scale in 2009 has very poor quality compared to what we had in 1920. Have you looked into that at all? With diabetes rates skyrocketing, and also gluten sensitivity, this may be an area where the better quality strains need to be rescued.

If you look up sources for varieties such as Emmer and Kamut you will find people keeping these heirlooms alive. They are even sold for high premiums in health stores for reasons you mention.

Modern wheat heirlooms are also interesting. The "trouble" with them from a present day farming perspective is that they aren't the double dwarf varieties that make combining smooth. Instead, they are tall and prone to lodging (i.e., falling over). They can be harvested mechanically by treating them like a hay crop, where the first pass is a cut only, and the second pass scoops and threshes. Triticale needs this treatment too, so it is not terrifically difficult, just a bit more costly.

Interestingly, the same thing happened to our local farmers' market last year. I attended the pre-season meeting that laid out all the regulations, costs and bueaucracy needed to conduct the next season's market. The decision was made to abandon selling baked or processed goods entirely, as the hassle was too great. I'm wondering if there was not a national campaign on the part of big business to squelch the growth of independent food production.

Not all locations are trending this way. In Virginia last year the legislature DROPPED the legal requirement for kitchen inspections for those selling baked goods at farmers markets. There is some push back.

Work with your local county agriculture specialists and have them help explain to your legislators how such regulations inhibit small agriculture business and thus adversely impact tax revenues. Find a champion to push the bill and see what happens. By creating exceptions for farmers markets a niche can be created that helps support the small scale grower.

Yesterday, for lunch, mom, my friend, my sister and I thoroughly enjoyed the black market rabbit. The rules are what they are - for the benefit of Hannaford, Whole Toxics, and whatever other industrial food-entity that feeds the politicians. But those rules and that whole system is not sustainable. And the quicker people break those rules - because they are meant to screw you and have no legitimacy - the better.

There was another post above that hinted at opt-in. Anyone joining a real co-op needs to opt-in. No cherry picking. If you want the benefits of one system, you have to stop using the system that is screwing you. It's time for co-op structures that require members to purchase from co-op or other similar vendors. If Food Inc is running a loss leader on poison milk, at half the price of the co-op, members agree not to buy it. Never, ever.

Furthermore, while Jason's argument is fine as far as it goes, it remains grounded in our current world view. Or it wants to be. [Goddamn google won't give me clean links any more - they value my search ability I guess.] Here, read the Dark Mountain manifesto. And as KMO discussed yesterday on C-Realm - a civilization is an organization of society that requires importation of resources from away. It's guaranteed unsustainable. We need to pay attention to how we define terms and words. Is a village a civilization? Is a sustainable society something we might typically call "civilized"?

Fixing, patching up - I think less and less there is any room for compromise with the existing structures. They need to be destroyed. Perhaps it is too late and they have already seduced and destroyed us, but there is no compromise.

cfm, The Growlery, Gray, ME

For an in-depth discussion of humanure composting, see Joseph Jenkins' book, The Humanure Handbook. This makes much more sense than our current practice of using potable water to transport human waste products to processing facilities.

http://www.humanurehandbook.com/about.html

I concur, though it is mentioned and linked in the article above.

From thermodynamics point of view there is one important flaw in the humanure technique: the waste of energy of bacterial activity.

More economic is to use methane producing bacteria in digesters and yield the biogas. I have read on the Digestion mailing list (highly recommendable:

Digestion@listserv.repp.org

http://listserv.repp.org/mailman/listinfo/digestion_listserv.repp.org

Beginner's Guide to Biogas

http://www.adelaide.edu.au/biogas/

Biogas Wiki http://biogas.wikispaces.com/

http://info.bioenergylists.org

that with composting about 60% of the original C content is used to transform the material into mature compost, finally ending up as CO2, leaving thus 40% for the soil. But with biogas digesters just 30% is used by the bacteria producing CO2, 20-30% is transformed into methane, ALSO leaving 40% in the form of residues for the soil!

Concerning the question of nitrogen: it seems better to apply directly the urine to the field, instead of everything to the compost heap. As long it is not directly sprayed on the vegetables it is a save fertiliser, directly profiting soil life instead of the compost bacteria (with risk of leaking to ground water, and transforming into nitrate).

Concerning phosphor: From a forestry professor of the university Laval in Canada I learned that phosphor is extremely well recycled within a good forest soil. The key issue for this nutrient therefor seems sufficient soil humus and returning most crop parts directly to the soil in a permanent cover (like in the forest).

That is interesting - our detailed knowledge of what really goes on and thinking in all-inclusive ways will turn out to be important.

Thanks for the numerical comparison.

Composting folks do make a distinction between the quality of aerobic and anaerobic decomposition. I know of practitioners who claim that the chemistry of the anaerobic process isn't so great for plants.

Any thoughts on that?

Reportedly, the traditional Chinese farmers composted both aerobically & anaerobically, and adjusted the inputs to their compost, according to the needs of the soil & of the crops. They didn't understand soil chemistry or plant physiology but could tell by examining the crop just how they needed to manipulate the compost to alleviate whatever the problem was, in order to maximize yield next year. I suppose that this traditional wisdom has been lost by now, but research on composting methods could conceivably restore some of it.

It seems logical: in anaerobic digestion just few organisms dominate, the methane producing bacteria, whilst with mature compost you bring an enormous biodiversity to your soil. Especially for soils that have been cultivated with lots of fungicides for a long time, compost is an efficient starter for bringing back life. Tradition does play a role. Science can only focus on a few organisms and its effects at the same time, under controlled conditions. It makes me think of the lacto-fermentation of camembert: a company, Lactalis, had found a bacteria that gave the typical camembert structure and taste to the cheese. Because people are afraid for the isteria bateria, this gave them the ability to kill of existing bacteria and make the cheese with their own one. In reality the taste is made by the combination of tens of varieties of fungi and bacteria, naturally present in Normandie. Only by co-incident and lots of trying and finally a set of beliefs and a code of practice (=tradition) the camembert became what it is. Lactalis wanted to change the code but they didnt manage...(after a strike of ofcourse :-) of the consumers)

anaerobic process isn't so great for plants

http://www.magicsoil.com/MSREV2/oxygen_realities_in_compost.htm

When some of the anerobic processes are things like alcohols - and alcohol is toxic to plant roots - then yes its not so great.

To keep things aerobic and low human-based energy one design is Paley's worm gin. Earthworms try to work material in 6 inches of space and thus airated. Downside - you have to monitor the moisture levels. http://www.jetcompost.com/wormgin/index.html

Jerry at jetcompost used to sell 'em (Ok now they are listed again)

http://www.jetcompost.com/ Yet 2 higher profiles sites no longer seem to use the worm gin design - one site in the Florida's penial system (2 years) and terracycle. If one follows terracycle's operation you'll note how they pre-process the to become worm food via a jetcompost unit and how the worm gin seems to no longer be in use based on photos. Not at all shocking given that Sir Howard noted brewery waste is not good for worms (rather high in Nitrogen) yet I can spread it thin on the ground and the local nightcrawlers will pick it up and drag it into their burrows. (course nightcrawlers will pick up condoms and fight over drag'n em to their burrows. They will also take cauk and try to make that food also.) Yet if the brewery waste is processed by something else 1st then the worms have no problem.

A mixed airation and worm process was done by a gent named Jay and talked about on the wormdigest.org site - claimed he was getting great results. Bubbling the air through water 1st makes sense to me if one was to try it.

"the waste of energy of bacterial activity"

Watch out for the transportation energy cost if you have to transport further to a biodigester.

Only local food is sustainable

H'mmm

New Orleans has had regular deliveries of bananas for two centuries, back to the age of sail.

Wheat cannot be grown locally, but it has also been in our diet for centuries (local rice is much more prevalent and the staple). Before rail & steamboats, Abraham Lincoln was one of thousands that took flat boats down river, sold the cargo and lumber from the boat, and walked home. Wheat was one of the cargoes, although whiskey, deer skins and tobacco had better profits.

Alan

There are many reasons why steamboats don't go up the Mississippi any more, or that Abraham Lincoln would find it difficult to take a flatboat full of produce down the river and sell it (and the boat) and walk back home.

One of the main reasons is that the steamboats all ran on wood, and the forests within hauling distance of the river were depleted. And cheap wood to make Abe's flatboat has long disappeared in the upper Midwest -- they need the land for Genetically Modified corn and soybeans. More profit.

Of course, the ancient Romans fed their people with wheat from North Africa. But look where that got them in the long run!

I live within walking distance of the Intracoastal Water Way.

I'm quite sure that there will continue to be plenty of exchange of foods and other goods along this trade route. I'm down in the tropical southern end, we have citrus, banana, avocados, mangoes just to name a few. I'd be glad to trade some of that for things that we can't grow locally.

Hey, we have sugar cane too! We could produce some good rum...

We don't need wood burning steamboats either.

http://www.core77.com/reactor/09.06_solarshuttle.asp

I wouldn't assume that wind-powered water vessels are viable on the majority ICW on a regular basis. So some form power would be required for transport in circumstances where there is not a sufficient downstream current (and in those situations, power would be required to return a vessel upstream).

Agreed! However I don't think steam produced by burning wood would be the only available option.

What power sources would you suggest?

I already posted this link

http://www.core77.com/reactor/09.06_solarshuttle.asp

Of course I'm biased that way.

However I think we should still have enough oil to be able to provide our transport barges with diesel. We have diesel electric boats where I live. Bio Diesel for fueling transport barges should be doable if we don't have to fuel millions of automobiles.

I remember seeing some rather large open ocean canoes used for transporting cargo over some pretty big distances that were powered by human arms and paddles that might work if worse comes to worst.

http://www.dkimages.com/discover/previews/1545/11731276.JPG

Batteries (powered by a wind/solar/nuclear grid) and direct wind propulsion, mostly.

See http://energyfaq.blogspot.com/2008/09/can-shipping-survive-peak-oil.html

Nukes.

DD is going to jump all over me now....................sh#t.

In the Puget Sound area some people are developing sail networks for food transport:

http://www.energybulletin.net/node/47620

Yes, though the wind resources there are far superior to conditions in much of the ICW. We have to be careful that we don't overgeneralize solutions that can result in unwarranted expectations.

Although I didn't discuss this because I like to keep things short and straight forward in the article, I did imagine that two regions could trade with each other in food stuff sustainably if transportation was very cheap (e.g., intracoastal water ways) AND they exchanged the same amounts of food so that composting the imports would yield the same returns as composting the traded local production.

Port locations have advantages, I concur. But you are arguing that because something has gone on for a long time it can continue to do so, which I know you don't actually believe.

Yeah, but how much does this need to bother us in practice? Even the universe itself can not continue forever, according to currently known physics. To exaggerate a little for clarity, you almost seem to be arguing that right now, you can't see a way for it (the port, the food supply, whatever) to go on absolutely unchanged for a million years, and right now, you decide somehow that the manner in which it now goes on can never change or adapt, and so it somehow follows that it urgently requires attention lest it stop or crash Real Soon Now.

In a more down-to-earth sense, it seems a bit like arguing that the food co-op down the street must close tonight because (like most retail stores) it's got far too little in the way of accounts-receivable dated tomorrow or later to sustain it. But in fact customers will arrive tomorrow, without the slightest need for a Soviet-style pre-planned roadmap-for-eternity to get them there; indeed many such businesses have operated that way for decades upon decades.

A discussion of forever may be an entertaining abstract meme to chew over, but to what extent is it a real problem for real people in any time-frame sanely of interest? To what extent does it merely reflect instead the perennial Soviet-style urge to plan what cannot be planned and compel what will not be compelled? And to what extent does it reflect extraneous philosophical quasi-religious attitudes and romantic maunderings of various sorts about food, farmers, agriculture, money, and perhaps a mythical past where everyone had abundant time to fritter away singing kumbayah around the campfire?

If peak oil and peak phosphorus are here or coming this century then it matters dearly I'd say. Nobody really knows when, exactly, but I don't find this a compelling reason not to bother. And I do much more than talk about this. My livelihood is in it.

Actually, I do see a way for it theoretically, but it is sociologically very daunting.

I agree with Alan that you will continue to see trading via our intracoastal waters, and I've posted before that here in Seattle, we're getting ready to wrap up the first year of operations for Sail Transport Company, a CSA that delivers produce petroleum-free and is informally partnered with the larger regional network of SCALLOPS (Sustainable Communities ALL Over Puget Sound). We've also had a couple business meetings with the Port of Seattle, and they've been supportive.

The crews are serious sailors and trips are done via sail, tidal currents, and home-crafted sculling oars only. No engines :-) Which did once lead to a near-cliffhanger situation when they docked at 9 AM on a Saturday morning and customer pick-up was due to start at 10 AM!

We also partner with local restaurants for their creative recipes based on some of the produce box's contents, and give them one side of the flyer to talk up their sustainability story: every single one sources their food from local farmers as much as possible. In an innovative example of what restaurants can do, when Jill Richardson, the author of Recipe for America: Why America's Food System is Broken and What We Can Do to Fix It, recently visited Seattle over Labor Day, we took her to the lovely French restaurant Bastille for brunch, which resulted in a nice write-up and pictures of their rooftop gardens (yes, they source their salads and herbs from here).

On The Other Coast note, when I went home for Christmas, I met with the Community and Government Affairs Manager for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey for their critique of this program. They thought STC was viable (we had a great discussion about the rejuvenation of the Erie Canal) and in fact, they already have the Port Inland Distribution Network (PIDN) in place: "...an extensive network of rail and barge services at our terminals to efficiently facilitate the flow of international cargo to points beyond our port."

I think you will see a great rebirth of sail and our waterways for transport. :-)

Just wanted to comment on the colorful logo at the top of this story... it is the North Dakota Department of Agriculture's local foods initiative and the people are interested in food systems can be found at www.goinglocalnd.ning.com. We'd love to hear from you.

Thanks for your work! I was thrilled to find an example from North Dakota, and not just from a food activist group, but from a government agency.

You have hit very close to why I believe some Bio-fuels are bad ideas. Grass for hay/biofuels requires Phosphorus and Potassium to grow. The Potassium is depleted rapidly when the grass is harvested. And yields per acre drop dramitically if not replaced. The plant nutrients must be replaced some how and I have yet to see how it can be economically or pratically. I do have a question though are the major plant nutrients phosphorus and potassium usable after the grass or other plant residue is burned as a fuel.

You make a good point. It seems like biofuels should not be considered sustainable because of this.

With some biofuels it is possible to close the loop for nutrients, except for nitrogen.

But this raises another point. Can anything be considered "sustainable"? What's the use even of using "sustainable" in a sentence, when the only possible sensible sentence, for any x, is said to be "x is not sustainable"?

Natural forests have sustained themselves for millions of years. As have coral reefs, wetlands, grasslands, deserts, swamps, etc. Permaculture methods that mimic nature are sustainable.

The problem is that industrial economies and consumer culture are not sustainable. You are only looking at the X’s that seek to continue these inherently unsustainable ways of living.

Most plants can't use elemental phosphourus, there are parasitic fungi that can though and trade phosphate ions for carbohydrates.

Arbuscular mycorrhiza

Switchgrass is a perennial crop which tests have shown takes

30# per acre of phosphorous and 45# per acre of potassium to establish.

So annually you need to replace .83# per ton of biomass

of phosphorous and 18.9# per ton of biomass of potassium, so a 10 ton per acre crop (producing 800 gallons of ethanol) would require 8.3# of phosphorus and 189# of potasium per year plus

100# of ammonia.

Compare this that corn ethanol where 800 gallons would require

110# of phosphorous and 130# of potassium and 300# of ammonia.

So cellulosic ethanol would require 8% of the phosphorous of corn, 145% of the potassium and 33% of the ammonia.

A 100 billion gallons of ethanol energy crop of switchgrass would take 518,750 tons of phosphorous and 1,181,250 tons of potassium.

The world resource in potash is 250 billion tons(7 billion US resource) and annual world production is 26 million tons( US 1.2 million tons).

The world reserve base in phosphate rock is 47 billion tons(3.4 billion US) and world production is 167 million tons/yr(30.9 million tons/yr US).

http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/phosphate_rock/mcs-2009...

When biomass is burnt or distilled into ethanol most of the minerals are removed as ash and are not lost but are recycled.

There is no looming shortage of potash whatsoever.

If you are worried about phosphate switch from corn to switchgrass for ethanol, reduce water runoff from fields and recycle ash back to the fields.

Stop worrying or at least give a quantitative reason why you are worrying.

When biomass is burnt or distilled into ethanol most of the minerals are removed as ash and are not lost but are recycled.

Unless the material is processed on the place where it is grown, the 'waste' will move with the same flow of money that shipped the switchgrass to the processing plant.

And even on a farm, the waste will end up in the farmers garden. (That is what a grazing animal does - move elements from the field to a more central location for processing) If they have a market garden, the S,P,K and other elements will be shipped off the farm to go into a sewer somewhere.

As an active gardner, composter and bird dog owner I never have and never will put dog**** in my compost pile.

Is this because of potentially harmful parasites?

And, as far as biosolids from wastewater treatment plants. They just started injecting that stuff into the soil around here, Mandan, ND. Someone suggested we use it at our new community garden site, but I said it was not considered safe for food crops because of the residual hormones, etc. from all the drugs people take? Anyone know anything about that aspect of this?

Critters with a flagellum may be more of a concern than drug residues. Antibiotics given to farm animals is an issue with methane digesters, the antibiotics kill the microbes that do the digestion.

This series of articles on sludge from last summer suggests you'd better watch out.

http://www.thestar.com/article/459345

Farmers split over safety

Free biosolids tempting at a time when prices of commercial fertilizer are skyrocketing

Jul 13, 2008 04:30 AM

Carola Vyhnak

Urban Affairs Reporter

The price is right. With savings of more than $100 an acre for fertilizer, the offer of free stuff is tempting for farmers struggling to make a living in the face of rising costs and diminishing returns.

Video: Sludge plant tour

http://www.thestar.com/fpLarge/video/458580

Slideshow: How sludge is made

http://www.thestar.com/fpLarge/photo/458680

SOILED LAND

Part I: Is sewage fertilizer safe?

http://healthzone.ca/health/article/459085

Where your waste goes

http://www.thestar.com/News/Ontario/article/459086

Part II: Farmers split over safety

http://www.thestar.com/News/Ontario/article/459345

Ill when wells contaminated

http://www.thestar.com/News/Ontario/article/459344

Oakville family sues

http://www.thestar.com/News/Ontario/article/459349

Part III: When rules are broken

http://healthzone.ca/health/article/459606

Sludge disease recognized

http://healthzone.ca/health/article/459607

Part IV: Food firms shun sludge use

http://www.thestar.com/News/Ontario/article/460264

Keeping sewage off fields a burning issue

http://www.thestar.com/News/Ontario/article/460263

Parasites and other pathogens are a problem with poop that comes from a dog or cat (i.e. carnivores). The other reason is that a carnivore leaves almost no organic matter because their diet consits primarily of protein & fat/oil, whereas a herbivore leaves a useable amount of organic matter because their diet consits primarily of cellulose/carbohydrates.

I am not saying that's a good idea. In general though, dog waste being treated as a landfill product is not sustainable. The question I pose is what are the alternatives?

Thermophilic anaerobic digestion or thermophilic aerobic composting?

I'm all for fewer drugs and more healthy eating.... I'm still trying to convince my spouse to pee near the garden in an attempt to keep the deer at bay?????

never will put dog**** in my compost pile.

What if you had some kind of cooker that heated it to 160+ degrees?