The Pringle as Technology

Company officials may not be sure, but I'm confident that the company copped their name from noted potato-related device inventor, Mark Pringle of New York

I didn't know it until today, but I have a very strong position on the age-old mystery of where the Pringles brand name originated.

In a New York Times story today about Proctor & Gamble's sale of the Pringles brand to Diamond Foods, the author noted this mystery: "Company officials still aren't sure how the chips got their name, but one theory holds that two Procter advertising employees lived on Pringle Drive in Cincinnati and the name paired well with potato."

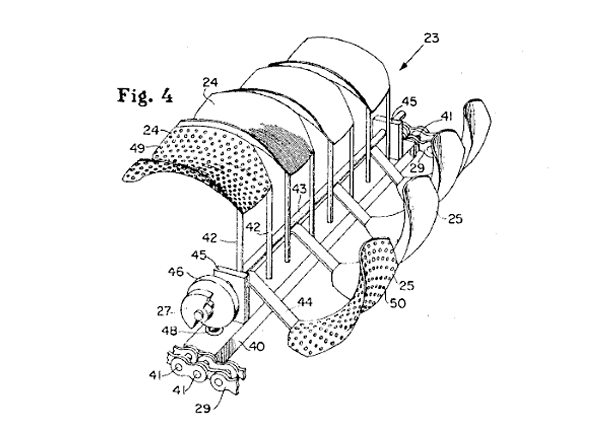

Company officials may not be sure, but I'm fairly confident that the company copped the name from noted potato-related device inventor, Mark Pringle of Amsterdam, New York. Pringle co-patented a "method and apparatus for processing potatoes" in 1942 that bears a striking resemblance to later methods of potato chip manufacture. He was, actually, trying to solve the same problem that Pringles later did. Namely, actually frying regular potatoes leads to irregularly-shaped chips of varying crunchiness that don't last on the shelf for very long.

Pringle's invention aimed to create chips that were "uniform in size, shape, color, color, and in all other characteristics" and that were of such uniformity that they could be "economically packaged in a very compact manner as to exclude any appreciate quantity of air." He didn't patent anything that was exactly a Pringle; that is to say, he had not quite gotten to the idea of chopping up all the potatoes, drying them into flakes, and then making a dough out of them, which is cooked into a saddle-shaped, potato chip-like food.

But it seems reasonable to me that the creators of Pringles may have named the chips after their fellow inventor as a kind of homage. The patent was actually cited by one of the Pringles' several corporate inventors, and by many others in the snack chip technology world. At the very least, it would be a most remarkable coincidence that a key patent-holder's name in their field happened to find its way onto a product.

Or it may have been that the syllables of Pringles were simply floating in the air surrounding the snack food world. After all, P&G had to pay off General Foods, which also named a snack food Pringles.

In any case, it is appropriate that the answer to Pringles' naming mystery would be found in the patent literature, as they were a harbinger of massive technological change in the food world. "Pringles, the stackable potato chip ... created a revolution," wrote Vince Staten in Can You Trust a Tomato? "No, not because you could stack them. A revolution in the potato chip delivery system." By creating a stackable chip that could be sealed in a container and shipped, P&G was able to get to sell the chips nationally, benefiting from economies of scale. It's actually like Ikea's flat-packed furniture model.

But first, they had to try to convince Americans that they even wanted such a chip. And in 1973, it seemed like the way to do it was to sell Pringles as a marker of technological progress. Better living through chemistry! Take a look at this most-excellent advertisement.

Three ladies are chatting at "Tuesday bridge club" when their host brings in the new type of potato chip. They stop talking, their mouths agape. In case you don't understand that they are shocked and awed, one lady pulls her reading glasses down her nose and we hear a dddooiiinnnggg sound. "Seems the Tuesday bridge club is simply amazed by Pringles newfangled potato chips," the voiceover man says. Newfangled is even written on the container! As the host pops open the can (so like a fresh three-pack of tennis balls), she says, "Now you girls really have something to talk about." The commercial's dialogue continues with Mamet-like speed and timing (emphasis added).

"Are there really potato chips in there?"

"I don't believe this."

"They're made a new way."

Then, the host slides out all of the Pringles in a line. Her guests cheer and say, "Ooooh!" One exclaims, "Beautiful!"

You might think from the commercial that people were impressed by the newfangled chips, but they weren't. The Times' story notes that Pringles were actually a flop until the 1980s when P&G came out with new flavoring and a fresh marketing campaign. I wouldn't be surprised if there was a more subtle dynamic playing out, too, in which Americans acceptance of ultraprocessed foods made it easier for these bizarrely uniform chips to find consumers willing to eat them.

UPDATE. As commenter JPeckJr notes about the commercial: "The unspoken question is 'Are those things food?'" People had to be trained into eating something that they did not immediately recognize as like the other foods they had eaten for their whole lives.

And as I argued before in my essay, SunChips and Supercapitalism, the convolutions of the food and food-like object industry lead us to some weird places.

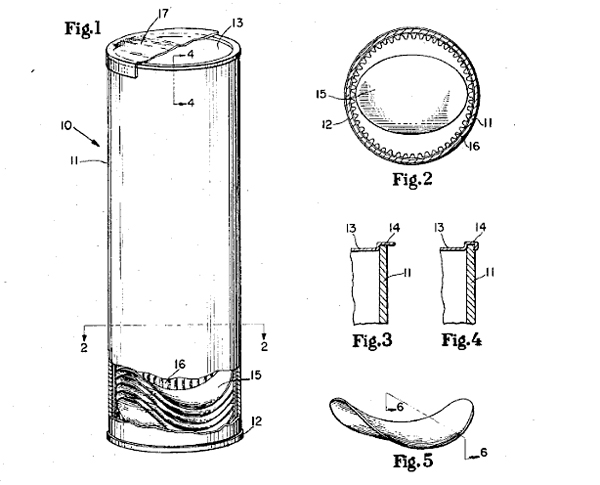

Images: 1. From Fredric Baur's can patent; 2. From Alexander Liepa's chip-making patent.