When the Internet Nearly Fractured, and How It Could Happen Again

When the entire country of Egypt was forced offline by its government last month, it served as a global wake-up call that the Internet is a more fragile medium than we imagine it to be. What happened in Egypt was particularly striking, but other, subtler tests of the Internet's resilience abound.

Turn your eye to the domain name system, for example. Commonly referred to as DNS, the domain name system is the obscure but almost unimaginably important process whereby memorable names like "TheAtlantic.com" get translated into the numbers that actually pinpoint The Atlantic's place on the Internet. There, in the innards of the Internet, there's controversy brewing. The Department of Homeland Security's Immigrations and Customs Enforcement division and the Department of Justice have been targeting domain names for takedowns, and the United States Senate is considering a bill that would empower the Attorney General to blacklist website names from the Internet's directories.

But this isn't the first time that DNS has been a contested space. In one particularly curious episode from the modern Internet's early days, a man named Eugene Kashpureff ignited a battle over the future of the global network that brought him face-to-face with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

* * *

It was the mid-1990s. The Internet was transitioning from the province of a limited pool of academics, engineers, researchers and enthusiasts into something bigger and more important. The White House was first beginning to really consider cyberspace as a place where the boom economic years of the early Clinton administration could be amplified and extended. While political history best knows Ira Magaziner as the point person on the eventually disastrous Clinton push to overhaul American health care as we knew it, he was also a central figure in the federal government's attempt to bump the Internet into its next stage of growth. Magaziner was the Clinton White House's Internet policy guru. (Magaziner would look back on his effort to corral and negotiate the strong personalities and strong interests at play in the early Internet into some sort of consensus as "every bit as daunting as creating national socialized medicine.")

A point of concern for the Clinton administration was that, somewhat amazingly, the Internet had gotten to the middle part of the decade running on a fairly ad hoc system for keeping track of numbers and names. In Virginia, a company called Network Solutions was contracted by the National Science Foundation to handle the bulk of domain name registrations on major top-level domains (.com, .org, etc.), through an entity called InterNIC. At the University of Southern California, a computer scientist named Jon Postel kept track of which Internet protocol address was tied to which computer server, under a contract with the Defense Department's R&D shop, DARPA. "It was a system," said Magaziner, in a 2006 interview with Internet archivist Carl Malamud, "that had been set up when the Internet was much smaller."

Clintonites were worried that the Internet was weak at a physical level. Business interests complained that the Internet wasn't nearly as secure and robust as it needed to be. Magaziner says he conducted an informal experiment. He visited the university basements housing some of the network's root servers. "I could have disconnected them [or] blown them up," said Magaziner, "and nobody would have noticed. So they had a point."

But perhaps more daunting, from the federal perspective, was how fragile and sometimes contentious the Internet's governance was. Network Solutions charged far too much for domain names, some critics argued, and it was getting rich off of providing a public service. There were those in Congress who said that the U.S. had a to keep a firm grasp on the Internet for it to be secure and stable. Others argued that the Internet would only really benefit the economy if it became a truly global network. DOD's role at the center of Internet governance weirded some people out. Commercial interests fretted about whether their trademarks would carry any weight when it came time to register domain names.

At the heart of the controversy, says Magaziner, was a culture clash. On the one hand, business interests were wary of the "quote-unquote hippies," as he puts it. Channeling the former, Magaziner said in his Malamud interview, "we can't commit our money based on their sort of anarchistic view of the world." As for the Internet people, including those self-appointed wise minds at the Internet Society, they held the flip side of that view. "These business types," said Magaziner, reflecting his take on what the early Internet community was thinking, "don't get the Internet [and] they're going to kill what's important about it."

In those mid-'90s years, said Magaziner in 2006, it wasn't at all clear that the Internet would turn out to be the global network where nearly any bit of information can be accessed and nearly any commercial transaction processed that we've come to take for granted. And in his sit-down with Malamud, Magaziner pointed out one example of why that future was in doubt: a now-forgotten service called AlterNIC run by one of those Internet-lovers, Eugene Kashpureff.

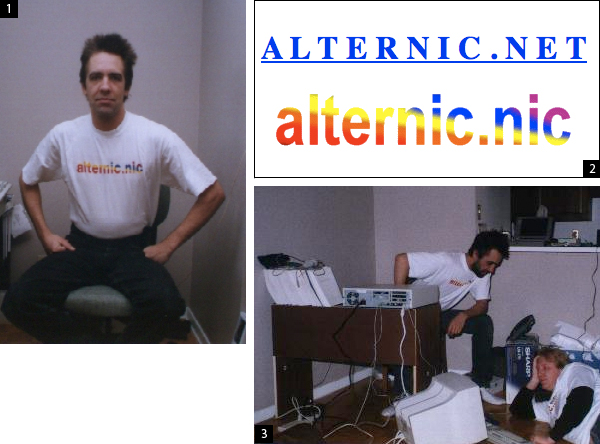

At the time, Kashpureff was an early-30s high-school dropout "doing computers and tow trucks," he said in a recent phone interview from San Jose. Perhaps he cut an unlikely figure to challenge to the global Internet, but he had the chutzpah and technical know-how to cause trouble. Kashpureff came to see that the Internet was coming increasingly under the control of a tiny "cabal" of academics, industry figures and government entities. And he wasn't going to just stand by and watch while the establishment took over.

Kashpureff chose DNS as his arena of protest. Every website, every e-mail, every embedded picture, every transaction--heck, nearly everything that happens on the Internet gets plugged into the domain name system, which went by the name InterNIC. At the time, thirteen root servers labeled "A" through "M" were scattered around the globe. Managed by small teams, they cascaded Internet traffic to an array of local registries. Together, those registries function as the global network's directory system. Without it, it would be nearly impossible to navigate a network of the Internet's complexity.

What Kashpureff did was launch something of a rogue registry, calling it AlterNIC. Kashpureff stayed away from registering websites on the big three "cabal"-run top-level domains: .com, .org and .net. Instead, for a small fee, anyone in the world could register a website on Kashpureff's alternative top-level domains, or TLD, like .alt., .biz., .news and .xxx. The new domains would be listed in Kashpureff's directory, and those of his allies on the Internet. It was a bid, he says, to boost the freedom of choice available to Internet users. "More names," he says when we talk, "just sounded like a good idea." And when you think about it: why should domain name registration be controlled by some random for-profit company appointed to do the holy work of maintaining one of the Internet's most basic functions?

In the summer of 1997, Kashpureff decided to ratchet things up. He opted to go a step beyond simply registering sites on alternative top-level domains, and hijacked traffic intended for InterNIC.net. He pointed the domain to his own site, where he lodged a note of protest over how the domain name space was being controlled, and then offered visitors the option of continuing on to Network Solution's site. This was, you'll recall, at about the same moment that the federal government was attempting to make the case to the business community, to the world, that this Internet thing was no digital Wild West. Did that give you pause?, I ask Kashpureff.

"Yeah, I thought twice about hitting that button," he says. "It was 4 o'clock in the morning on a Saturday, and I had probably been smoking all night long. Can you imagine it? I'm sitting in the middle of nowhere Washington [State] on a T1 line to the Internet, and I'm hitting that damn button?"

It might have been, in practice, the simple mashing of a button, but it had the effect of triggering a major moment in the evolution of both the Internet and Eugene Kashpureff. Kashpureff sat, he recalls now, and watched as the hit came in from the Virginia computer of the CEO of Network Solutions, who expected to turn up his own site and instead found AlterNIC's. Eventually, the Feds brought wire fraud charges against Kashpureff, holding that he diverted traffic from InterNIC to AlterNIC twice, once between July 10 and 14, and again between July 21 and 24.

Kashpureff had been spending time in Canada, and on Halloween of 1997, the Mounties came knocking. I asked Kashpureff why he thinks the might of law enforcement in both Canada and the U.S. came crashing down on him. "He was some yahoo," he says of himself, "who had the keys to the Holy Grail." That is, this random guy had the ability to manipulate the structure of the Internet's domain name system.

Network Solutions claimed hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost registration fees. Kashpureff spent months in Canadian prison fighting extradition. The March 1998 press release from the U.S. Attorney's Office announcing Kashpureff's eventual guilty plea noted almost gleefully that they'd punished the "self-described 'webslinger.'" Kashpureff apologized. He never, he says now, intended for his escapades to be turned into, well, a federal case. "Back then, everything was supposed to be a model. We were supposed to be having fun," he says with a wry laugh. "And people want to come arrest me for that?

Indeed they did. And more. AlterNIC earned Kashpureff some fans and many enemies. During the AlterNIC years, Paul Vixie ran the Berkeley Internet Domain Name software, a.k.a. Bind, the digital infrastructure that powered much of the DNS system. It was a weakness in BIND, it seems, that Kashpureff exploited to take over the InterNIC domain name. For decades, Vixie has been a major figure in the Internet numbering and naming world. AlterNIC drove Vixie mad in the '90s, and still does. As Kashpureff faced prosecution, a note went out on the mailing list of the North American Network Operators, asking for contributions for his legal defense fund. Vixie's response: "How much do I have to pay to keep him in jail forever?"

Vixie contends that it wasn't just Kashpureff's hijacking of the InterNIC domain that was offensive. It was the indulging in propagation of alternative domains outside the consensus of the Internet community itself. Splintering DNS forks the Internet so that Internet users might never know where to go to get domains, or what they might get. If they connected to some DNS directories, they might enter Coke.com and get Pepsi. Chaos could ensue. All for what Vixie sees as not a noble question to uphold the free spirit of the Internet but instead a self-serving marketing stunt intended to promote Kashpureff's own business. Some things, writes Vixie, should just work, and DNS is one of them. The domain name system can't be subject to "the law of the jungle or the survival of the richest," he wrote to me. Because an Internet with a fractured domain name system doesn't much resemble the global Internet anymore.

* * *

There are two funny things in this preview of our more contentious Internet age.

The first: the Eugene Kashpureff of today seems to agree, in large part, with the Paul Vixie of yesterday and today, at least as far as the necessity for stability and security on the Internet goes. Kashpureff says that the attacks of September 11, 2001, helped to trigger something of a change of heart. He now works widely in the Internet engineering field, often to build up secure online spaces. "People have no clue what debt we owe people like Paul Vixie," says Kashpureff. "Nowadays, I make sure that no one gets away with what I did ever again."

The second: the DNS threats of today don't seem to be coming as much from the Eugene Kashpureffs of the world--solo hackers and coders--as they seem to be coming from world governments, particularly the United States government.

This is a reversal for a country that did so much in the modern Internet's early days to unite constituencies around the importance of integrity when it comes to the Internet's domain name layer.

During and after Kashpureff's protest, slowly, and perhaps improbably, a U.S.-led working consensus about the management structure of the domain name system emerged. Eventually, the Clinton administration's Commerce Department would lay out what became known as the Green Paper, which, with feedback from a wide range of people and bodies in the U.S. and abroad, set out a plan for how the modern Internet would function. Central to the plan was the creation of something that came to be known as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, or ICANN. A California-based non-profit officially established in 1998, ICANN still today governs the Internet's technical operations, under an agreement with the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Closer to home, various parts of the United States government have, in recent days, shown an increased eagerness to enlist DNS in their political and legal battles. The Department of Homeland Security's ICE division and the Justice Department have been teaming up on DNS targeting initiatives called things like "Operation In Our Sites" and "Operation Protect Our Children." Sites thought to engage in offensive behaviors, from distributing child pornography to connecting people to downloads of music and movie files protected by copyright, have been shutdown at the domain name level, their normal contents replaced by a banner reading "This domain has been seized." Cyber Monday after this most recent Thanksgiving saw more than 80 domains thus disappeared. Last week, DHS and DOJ had to admit that they had inadvertently caused the pulling down of more than 80,000 "innocent" websites that had be co-located with sub-domains that were targeted in their operations. "A higher level domain name and linked sites were inadvertently seized for a period of time," read the joint release, though the feds assured that they quickly allowed the sites back up.

And then there's COICA, the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act introduced by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) at the behest of the music and movie industries. At least in its initial draft, the bill would empower the U.S. Attorney General to blacklist domains found to be offensive for "infringing activities." The Washington-based Center for Democracy and Technology argues that in its bid by the Senate to ensure that the Internet is safe for commerce, Washington threatens to signal to the world a reversal of years of American policy, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, that has worked to "reassure the global community that the United States would not abuse its position of oversight over the DNS."

If COICA is enacted, writes CDT in its analysis, the bill would mark "a significant step towards the balkanization of the Internet." What happens, suggests Vixie, when Bollywood decides that it wants the same power to demand domain takedowns as Hollywood seems to have?

With the U.S. government's recent domain name power grabs, ICANN's continued position at the heart of the Internet has become part of an ongoing global debate over whether the U.S. has far too much power over how the Internet works. There's been a considerable push to transfer power away from ICANN and towards an internationally accountable organization, like the International Telecommunications Union. At the World Summit on the Information Society in Tunisia in 2005, a last-minute agreement emerged that affirmed ICANN's central role, but it was and remains a shaky consensus.

The next year after the Tunis agreement, China, for example, began to make noises about setting up its own DNS registries for the .com domain, so that "Internet users don't have to surf the Web via the servers under the management of the ICANN of the United States," as the Communist Party's People's Daily put it. In March of last year, ISPs around the world reportedly began inadvertently using Chinese DNS servers that had been configured to enforce the so-call Great Firewall. Internet users in the United States and Chile suddenly found themselves unable to get to sites like Twitter, YouTube and Facebook.

The question for the short term is whether the federal government of the United States, so long the cultivator and protector of the Internet's domain name system, might turn out to be a greater threat to it than Eugene Kashpureff ever was. For his part, Paul Vixie is taking the long view. All we have to manage to do, writes Vixie, is to not completely screw up the Internet's domain name system for another fifty years or so. By that time, we'll likely have moved to the next world-changing way of doing things.

Kashpureff is less sanguine, casting his old work as a battle against precisely the kind of intrusions that we're seeing today.

"[AlterNIC] was about literal United States government control of the Internet, and that still exists today," he said. "It ain't never gonna change."

Images: Eugene Kashpureff.