A newly announced partnership between the world’s biggest private coal mining company and coal-burning country cuts against recent efforts to paint China green because of its push on manufacturing wind

turbines and solar panels. All of its efforts on renewable energy come atop ongoing expansion of its use of coal.

In a news release issued today, the coal company, Peabody Energy, gushingly describes the

company’s partnership with the government of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region and Communist Party on a plan to develop a surface coal mine that will produced 50 million tons of coal a year “over

multiple decades.” The news is summarized well by James Areddy and Simon Hall in The Wall Street Journal.

I sent the release to a few experts on coal and carbon dioxide for their reactions. David Victor, the University of California, San Diego, political science professor and author of “Global Warming Gridlock,”

noted some subtler aspects of the announcement that point to ever more efficient coal use in China, but also unrelenting growth in coal use — and carbon dioxide emissions. Here’s Victor’s

reaction:

I think the really big story here — from the perspective of the industry — is that China is in the midst of a massive consolidation of its coal industry and a bunch of other efforts, including a larger role for best practice foreign operators

like Peabody, that are designed to maximize output of coal and lower the costs, which have skyrocketed. All that points in the direction of making coal more competitive than it has been in the past.

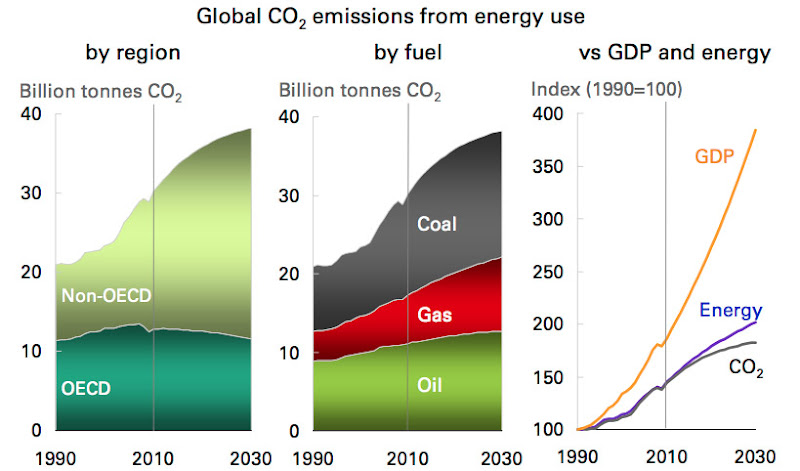

Barring a big change in technology and regulation on CO2, that trend is hard to square with widely discussed goals for stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations. If it is any consolation, the average

efficiency of coal plants in China has been rising decisively—that doesn’t bend down the emissions curve, but it slows the growth.

Here are a couple of descriptions of the pace of growth in coal use from the Peabody release:

The Xinjiang Region is China’s largest administrative region with vast reserves of coal estimated to account for approximately 40 percent of China’s reserves. The government expects Xinjiang’s coal output will increase from approximately

100 million tonnes in 2010 to more than 1 billion tonnes.

China is the world’s fastest-growing economy and the world’s largest energy user. The nation is expected to bring online 600 gigawatts of coal-fueled electricity generation by 2035 according

to the International Energy Agency, which would require more than 2 billion tons of coal each year. This year alone, China is expected to increase its coal-fueled power capacity by 50 gigawatts, representing

several hundred million tons of additional annual coal use.

Here’s the reaction from Raymond T. Pierrehumbert, a climate scientist at the University of Chicago who has weighed in on Dot Earth on questions raised

by

the ever growing flow of coal exports to China from industrialized countries — notably the United States and Australia:

We have no control over the coal China mines on its own land, but there’s no reason we (and Australia) ought to be bending over backwards to sell them coal we do have control of. Obama has authorized expanded coal mining in Montana, and there will

be a push to expand coal export terminals for exports to Asia.

Bigger things are already happening in Australia. We in the developed world can decide to leave this coal in the ground, if only we had the courage to do so. Every tonne of coal left in the ground is one

less tonne in the atmosphere/ocean contributing to long term climate change. It’s pointless to pearl-clutch (oh golly) over China’s mining and say there’s nothing we can do in the

face of a big bad thing like THAT.

Every tonne counts, and any tonne of carbon we keep out of the atmosphere is an improvement, whether or not it offsets China’s coal mining. For that matter, even in China one has to look at the fact

that their substantial investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency means that at least their emissions are increasing at a much lower rate than they might be.

So, the fact that China is expanding coal mining has zero relevance to the climate benefits to be had by reducing our own emissions. A tonne saved is still a tonne saved. What IS gruesome, though, is that

the first world sends coal to China to burn to make the junk we buy from them, and then we hand-wring about how China is burning so much coal it’s hopeless for little old us do do anything about

CO2 emissions.

Here’s more on these issues:

The Coal Age Continues

Big Coal Booming on Earth Day

From Green-Weiskel et al, “

From Green-Weiskel et al, “