When the Wikileaks releases exploded onto the news agenda last year, they changed many things - international diplomacy, the conduct of war and national secrecy. Perhaps lesser-realised is how they changed journalism. Wikileaks didn't invent data journalism. But it did give newsrooms a reason to adopt it. There was just too much data for it to happen any other way. As the Guardian publishes the definitive account of how we covered Wikileaks, this is the Datablog guide to what we did with the numbers.

This is about how we handled that data, how we extracted stories from it. We've had to handle major datasets before, such as the release of the treasury's huge spending database (Coins) earlier last year. With the WikiLeaks files we had the same criteria of success: help our journalists access the information, break down and analyse the data – and make it available for our users.

Click on a headline to read more. Or click here to see all our Wikileaks data journalism.

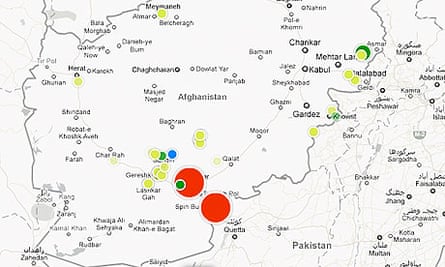

Afghanistan, July 2010

This is some spreadsheet: 92,201 rows of data, each one containing a detailed breakdown of a military event in Afghanistan. This was the WikiLeaks war logs. Part one, that is. There were to be two more episodes to follow: Iraq and the cables. The official term was SIGACTS: the US military significant actions database. Recorded by soldiers in the field, this was war as it as fought, complete with military jargon and incredible detail.

It was central to what we would do quite early on that we would not publish the full database. Wikileaks was already going to do that and we wanted to make sure that we didn't reveal the names of informants or unnecessarily endanger Nato troops. At the same time, we needed to make the data easier to use for our team of investigative reporters led by David Leigh and Nick Davies (who had negotiated releasing the data with Julian Assange). We also wanted to make it simpler to access key information for you, out there in the real world – as clear and open as we could make it.

The data came to us as a huge excel file – 92,201 rows of data, some with nothing in at all or poorly formated. We also started filtering the data to help us tell one of the key stories of the war: the rise in IED (improvised explosive device) attacks – home-made roadside bombs which are unpredictable and difficult to fight. This dataset was still massive – but easier to manage. There were around 7,500 IED explosions or ambushes (an ambush is where the attack is combined with, for example, small arms fire or rocket grenades) between 2004 and 2009. There were another 8,000 IEDs which were found and cleared. We wanted to see how they changed over time – and how they compared. This data allowed us to see that the south, where British and Canadian troops are was the worst-hit area - which backed-up what our reporters who had covered the war knew.

The casualties data brought its own challenges, repeated again when we dealt with the Iraq data. It was often inaccurately compiled and incomplete – we compared Nato-recorded casualties too, to test the veracity of the data, and the results varied.

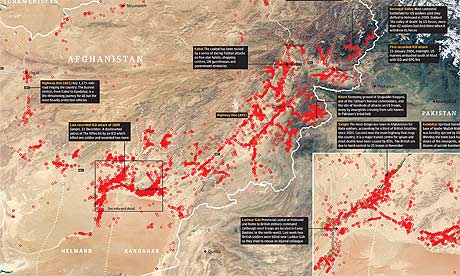

Iraq, October 2010

This article includes content provided by Spotify. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

The Iraq war logs release dumped another 391,000 records of the Iraq war into the public arena. This was in a different league to the Afghanistan leak - there's a good case for saying this made the war the most documented in history. Every minor detail was now there for us to analyse and break down. But one factor stood out: the sheer volume of deaths, most of which are civilians.

We also took all these incidents where someone had died and put it on the map above. It was not perfect, but a start in trying to map the patterns of destruction which had ravaged Iraq.

But the release raised questions over the quality of the data. Academic Jacob Shapiro at Princeton had worked with SIGACTS and pointed out that there is under-reporting in the data because:

there was no Coalition or Iraqi unit around to record the death; the Coalition and Iraqi units in the area were engaged in such high levels of combat that did not have time to track down every casualty on all sides; or the outcome of the incident was ambiguous

So, although the data painted a grim picture, the facts were likely to be much, much worse, because of underreporting.

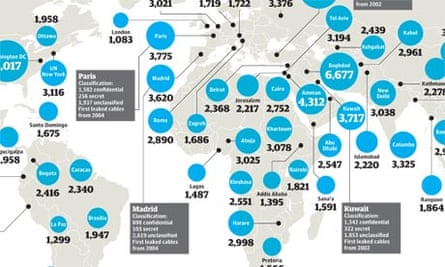

US embassy cables, December 2010

This was in another league altogether, a huge dataset of official documents: 251,287 dispatches, from more than 250 worldwide US embassies and consulates. A unique picture of US diplomatic language - including over 50,000 documents covering the current Obama administration.

The cables themselves came via the huge Secret Internet Protocol Router Network, or SIPRNet. SIPRNet is the worldwide US military internet system, kept separate from the ordinary civilian internet and run by the Department of Defense in Washington. An increasing number of US embassies have become linked to SIPRNet over the past decade, so that military and diplomatic information can be shared. By 2002, 125 embassies were on SIPRNet: by 2005, the number had risen to 180, and by now the vast majority of US missions worldwide are linked to the system - which is why the bulk of these cables are from 2008 and 2009.

There were

• 251,287 dispatches

• The state department sent the most cables in this set, followed by Ankara in Turkey, then Baghdad and Tokyo

• 97,070 of the documents were classified as 'Confidential'

• 28,760 of them were given the tag 'PTER' which stands for prevention of terrorism

• The earliest of the cables is from 1966 - with most, 56,813, from 2009

But, the data being what it was our reporters ended up with the enormous task of actually going through each cable, reading it and seeing what stories were there. It's an enormous task, which is still going on, and we've enlisted the help of our readers to come up with ideas they want to see investigated. It's a task which may never be entirely finished - until the next huge data release which again changes the way journalism works.

What happens next?

Sometimes people talk about the internet killing journalism. The Wikileaks story was a combination of the two: traditional journalistic skills and the power of the technology, harnessed to tell an amazing story. In future, data journalism may not seem amazing and new; for now it is. The world has changed and it is data that has changed it.

More data

Data journalism and data visualisations from the Guardian

World government data

Search the world's government data with our gateway

Development and aid data

Search the world's global development data with our gateway

Can you do something with this data?

Flickr Please post your visualisations and mash-ups on our Flickr group

Contact us at data@guardian.co.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion