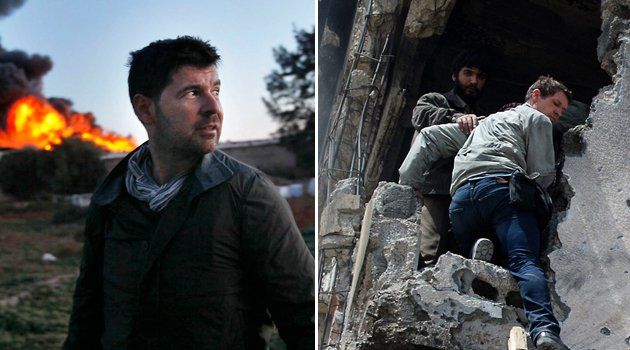

The news bludgeoned me on a sunny Australian morning. Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros had been killed on a rebel front, in a besieged city, bearing witness.

I last saw Tim in Brooklyn. In what was the worst and darkest of all years for me, 2009, Tim lived a few doors down the hallway in a Williamsburg warehouse converted to a warren of lofts. For me, it was the first time since 9/11 that I'd attempted to live outside of war, and I hit New York like a meteor plunging to earth. Each day, I vanished a little bit more on that black living-room couch until I was transparent, if not invisible altogether. Writhing with a pain I couldn't understand, I caused nothing but pain to those around me. And yet there was Tim.

Though Tim and I hadn't known each other in war but in Brooklyn, we easily recognized the war within each other. In a quiet moment, one of all too few I was lucky to have with him, I remember him telling of the trial it was merely venturing outside and shopping at the store on our corner barely a block away.

That tore at me, for it was something I struggled with too, though far less stoically than he did. While I spent that year inanely trying to dull my pain, leaving the apartment rarely save for CNN live shots or visiting more war, Tim, it seemed to me, persevered. And did so with a quiet, elegant grace, distinguishing him from the white noise that was anyone else I met at that time. He was a man I hoped to be, but now know I shall never become.

Chris I remember well from far too many war zones. Seeing him was always a pleasure, his presence never failing to offer respite from whatever mayhem surrounded us. I search now in the bowels of my computer for our correspondence, long since truncated by the isolation of my own selfish retreat into personal horrors. Way down here in Brisbane, I howl with fury into the night for archives I didn't save or which were lost with the demise of each of my computers battered in Iraq. I just felt him slip tremendously away, a sense of my betrayal at failing him further souring me.

In the field, where, as the soldiers say, "the meat meets the metal," I've found that I gravitate to photographers, the ones who come the closest to revealing the truth, even if we never get to the entire truth. In war, everyone lies; their government, our government, the rebels—even civilians lie through exaggeration or confusion. But what we can get is the shards of truth, like Tim's photo of a wretchedly filthy, dog-tired American grunt in the Korengal Valley, holding his face in his hand, or Chris's picture of a little girl with her parents' blood splattered over her dress, after American soldiers killed them at a Tal Afar checkpoint. (See previous spread.)

War photographers and reporters, of course, are not immune to this pain. But when you're in a conflict, you can't afford to think about how you're feeling. You're trying to capture the tremendous hurt of the war, but at the same time, you can't afford to feel it yourself. And unlike the soldiers, who live in an environment conditioned to deal with these things, war journalists often find themselves alone in the newsroom, with no one to share the experience with.

People ask, "Why do it?" At first, it was exciting to witness these forces of history colliding, and I found it hard to stand idly by. Eventually, I became so inured to the violence, the war became my normal.

I remember talking to a Marine in Iraq during a breather between firefights in Ramadi. I told him, "When I go home, people ask, 'What's the worst thing you've seen?' " "What do you tell them?" he asked. "I say, 'You haven't earned the right to know.'" He went quiet for a while. "You know what they ask me when I go home?" he asked. " 'So how many people have you killed?'" "And what do you tell them?" I asked. "I tell them," he said, " 'That is between me and the dead.'"

It was a photographer, the great, lost love of my life, who finally saved me. Over six months of long, late-night phone calls to Baghdad, it was she who told me it was OK to come home. Though the war eventually defeated our relationship, this photographer's wisdom continues to guide me.

And then there is my son, Jack, a George W. Bush war baby, conceived after Operation Anaconda in Afghanistan in March 2002, and born in January 2003. I left him when he was 21 days old to cover the invasion of Iraq, and for his entire life his dad was at war. It was only when I left CNN last year, and came to be with him here in Australia, that I started healing. Were it not for my son, I shudder to think what would have happened.

Coming home, though, was the hardest. I realized I was in trouble one evening when I was driving along the road, and the car in front of me set off the speed-camera flash. I didn't see a speed camera; I saw the explosion of an IED.

Those who have seen war are never the same again. We see the world through different eyes, and I consider that a privilege. I am the custodian of all these stories, and I belong to a fortunate tribe. I walk with ghosts.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.