Once upon a time, not so long ago, no one thought that there was a mind-body problem. No one thought consciousness was a special mystery and they were right. The sense of difficulty arose only about 400 years ago and for a very specific reason: people began to think they knew what matter was. They thought (very briefly) that matter consisted entirely of grainy particles with various shapes bumping into one another. This was classical contact mechanics, "the corpuscularian philosophy", and it gave rise to a conundrum. If this is all that matter is, how can it be the basis of or give rise to mind or consciousness? It seemed clear, as Shakespeare observed, that "when the brains were out, the man would die". But how could the wholly material brain be the seat of consciousness?

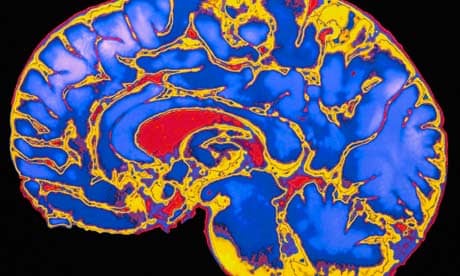

Leibniz put it well in 1686, in his famous image of the mill: consciousness, he said, "cannot be explained on mechanical principles, ie by shapes and movements…. imagine that there is a machine [eg a brain] whose structure makes it think, sense and have perception. Then we can conceive it enlarged, so that we can go inside it, as into a mill. Suppose that we do: then if we inspect the interior we shall find there nothing but parts which push one another, and never anything which could explain a conscious experience."

Conclusion: consciousness can't be physical, so we must have immaterial souls. Descartes went that way (albeit with secret doubts). So did many others. The mind-body problem came into existence.

Hobbes wasn't bothered, though, in 1651. He didn't see why consciousness couldn't be entirely physical. And that, presumably, is because he didn't make the Great Mistake: he didn't think that the corpuscularian philosophy told us the whole truth about the nature of matter. And he was right. Matter is "much odder than we thought", as Auden said in 1939, and it's got even odder since.

There is no mystery of consciousness as standardly presented, although book after book tells us that there is, including, now, Nick Humphrey's Soul Dust: The Magic of Consciousness. We know exactly what consciousness is; we know it in seeing, tasting, touching, smelling, hearing, in hunger, fever, nausea, joy, boredom, the shower, childbirth, walking down the road. If someone denies this or demands a definition of consciousness, there are two very good responses. The first is Louis Armstrong's, when he was asked what jazz is: "If you got to ask, you ain't never goin' to know." The second is gentler: "You know what it is from your own case." You know what consciousness is in general, you know the intrinsic nature of consciousness, just in being conscious at all.

"Yes, yes," say the proponents of magic, "but there's still a mystery: how can all this vivid conscious experience be physical, merely and wholly physical?" (I'm assuming, with them, that we're wholly physical beings.) This, though, is the 400-year-old mistake. In speaking of the "magical mystery show", Humphrey and many others make a colossal and crucial assumption: the assumption that we know something about the intrinsic nature of matter that gives us reason to think that it's surprising that it involves consciousness. We don't. Nor is this news. Locke knew it in 1689, as did Hume in 1739. Philosopher-chemist Joseph Priestley was extremely clear about it in the 1770s. So were Eddington, Russell and Whitehead in the 1920s.

One thing we do know about matter is that when you put some very common-or-garden elements (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sodium, potassium, etc) together in the way in which they're put together in brains, you get consciousness like ours – a wholly physical phenomenon. (It's happening to you right now.) And this means that we do, after all, know something about the intrinsic nature of matter, over and above everything we know in knowing the equations of physics. Why? Because we know the intrinsic nature of consciousness and consciousness is a form of matter.

This is still a difficult idea, in the present climate of thought. It takes hard thought to see it. The fact remains that we know what consciousness is; any mystery lies in the nature of matter in so far as it's not conscious. We can know for sure that we're quite hopelessly wrong about the nature of matter so long as our positive account of it creates any problem about how consciousness can be physical. Some philosophers, including Humphrey's long-time collaborator, Daniel Dennett, seem to think that the only way out of this problem is to deny the existence of consciousness, ie to make just about the craziest claim that has ever been made in the history of human thought. They do this by changing the meaning of the word "consciousness", so that their claim that it exists amounts to the claim that it doesn't. Dennett, for example, defines consciousness as "fame in the brain", where this means a certain kind of salience and connectedness that doesn't actually involve any subjective experience at all.

In Soul Dust, Humphrey seems to agree with Dennett, at least in general terms, for he begins by introducing a fictional protagonist, a consciousness-lacking alien scientist from Andromeda who arrives on Earth and finds that she needs to postulate consciousness in us to explain our behaviour. The trouble is that she's impossible, even as a fiction, if Humphrey means real consciousness. This is because she won't be able to have any conception of what consciousness is, let alone postulate it, if she's never experienced it, any more than someone who's never had visual experience can have any idea what colour experience is like (Humphrey says she'll need luck, but luck won't be enough).

Humphrey also talks in Dennettian style of "the consciousness illusion" and this triggers a familiar response: "You say that there seems to be consciousness, but that there isn't really any. But what can this experience of seeming to be conscious be, if not a conscious experience? How can one have a genuine illusion of having red-experience without genuinely having red-experience in having the supposed illusion?"

Later, Humphrey seems to be a realist about consciousness. When he comes to the question of how human consciousness evolved, his remarkable suggestion is that it is adaptive and has survival value principally because it allows for "self-esteem, coupled with self-entrancement". "Your Ego… this awesome treasure island… never ceases to amaze and fascinate you." And since this is tremendously pleasurable, you very much want to go on living. The gloomier among us may doubt this, finding Hamlet nearer the mark. The deeper problem with the self-entrancement theory is that natural selection can select implacably for an intense instinct of self-preservation without using consciousness at all.

It seems to me, then, that Humphrey's central contentions are hopeless. One doesn't solve the problem of consciousness (such as it is) by saying that consciousness is really a kind of illusion. Whatever difficulties there are in explaining the survival value of consciousness, it doesn't lie in the fact that it makes self-entrancement possible. There is initially something disarming about the rapturous self-confidence of Soul Dust, but it comes in time to seem mere vanity.

Galen Strawson is professor of philosophy at the University of Reading

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion