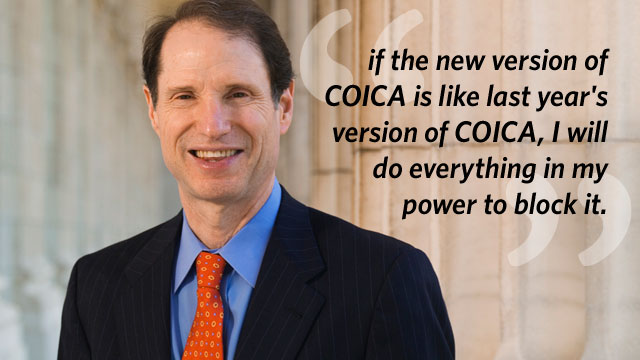

Start talking about the Web censorship legislation currently being drafted in both chambers of Congress, and Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) becomes an instant quote machine. This isn't just another of the many political issues Wyden has to juggle; the man cares about the Internet. And in his passion to defend it, he's not afraid to ruin his chances of becoming the next ex-senator to head the Motion Picture Association of America.

"You get a lot of folks expressing increasing concern that essentially one part of the American economy, the content industry, is trying to use government as a club to beat up on one of the most promising parts but the economy of the future—the Internet," Wyden told me last week when we talked about the issue. "These major content lobbyists shouldn't be provided the authority to cluster bomb on the 'Net."

The cluster bomb in question here is COICA, the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act, first introduced in the Senate late last year. It passed unanimously out of committee, though it did not get a full vote before the end of the Congressional term. This year, both chambers are drafting tweaked versions of COICA, due to be rolled out separately in the next few weeks, and the House recently held two hearings on the issue.

COICA allows the government to block sites at the domain name (DNS) level, and it would require online ad networks and credit card companies to stop working with blocked sites. The goal is to target foreign piracy and counterfeiting sites that can't be easily reached through US courts. The blocks would require judicial sign-off, but most hearings would feature only the government's point of view, and rightsholders would largely supply the target list to government investigators.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...