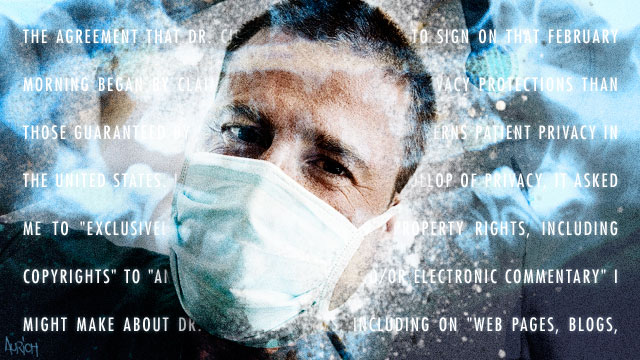

When I walked into the offices of Dr. Ken Cirka, I was looking for cleaner teeth, not material for an Ars Technica story. I needed a new dentist, and Yelp says Dr. Cirka is one of the best in the Philadelphia area. The receptionist handed me a clipboard with forms to fill out. After the usual patient information form, there was a "mutual privacy agreement" that asked me to transfer ownership of any public commentary I might write in the future to Dr. Cirka. Surprised and a little outraged by this, I got into a lengthy discussion with Dr. Cirka's office manager that ended in me refusing to sign and her showing me the door.

The agreement is based on a template supplied by an organization called Medical Justice, and similar agreements have been popping up in doctors' offices across the country. And although Medical Justice and Dr. Cirka both claim otherwise, it seems pretty obvious that the agreements are designed to help medical professionals censor their patients' reviews.

The legal experts we talked to said that the copyright provisions of these agreements are probably toothless. But the growing use of these agreements is still cause for concern. Patients who sign the agreements may engage in self-censorship in the erroneous belief that the agreements bar them from speaking out. And in any event, the fact that a doctor would try to gag his patients raises serious questions about his judgment.

As we dug into the story, we began to wonder if Medical Justice was taking advantage of medical professionals' lack of sophistication about the law. Doctors and dentists are understandably worried about damage to their reputations from negative reviews, and medical privacy laws do make it tricky for them to respond when their work is unfairly maligned. Although Dr. Cirka declined repeated requests for an interview, his emailed statements (and the statements of his staff) suggest he doesn't understand the terms of the agreement he asks his patients to sign.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...