The Future of Media Bias

Context can affect bias, and on the Web -- if I can riff on Lessig -- code is context. So why not design media that accounts for the user's biases and helps him overcome them?

I have a good friend who writes for a very conservative political website, and whose views on politics I respect. Though I strongly disagree with him, he frequently challenges me to think harder about my own politics, so I try to read his writing as much as I can.

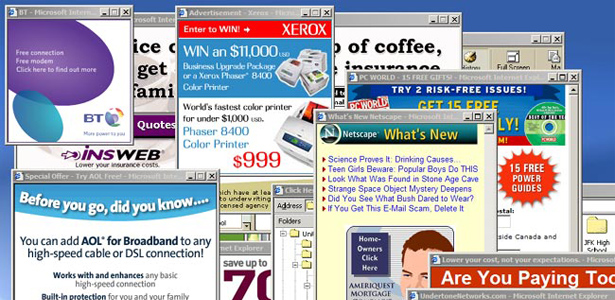

But there's a problem. When I visit the site to read his posts I'm hit with pop-up ads trying to sell me red-meat conservative titles like The Roots of Obama's Rage (Dinesh D'Souza) or Demonic: How the Liberal Mob is Endangering America (Ann Coulter). As a liberal, these ridiculous titles are enough to get under my skin, and so by the time I've bypassed the pop-up and made it to my friend's post, I'm all riled up and that much less likely to give his arguments a fair shake.

While I hate to admit that something as silly as a pop-up can alter my tolerance for opposing arguments, this case is instructive. It points to shortcomings in how we reason, and suggests how we might design media to help us reason better.

First off, this example is a reminder of just how hard it is to overcome our own political biases. As hard as we try, we are a far cry from our ideal of rationality, forming beliefs based on facts and figures. Instead, our rational faculties are frequently put to use finding reasons to confirm our existing prejudices. When we confront new evidence, our emotions play a central role in how we react. This tendency, known as "motivated reasoning," has been well documented by psychologists, and was recently explained in an excellent and accessible essay in Mother Jones by writer Chris Mooney. As Mooney aptly describes it:

The theory of motivated reasoning builds on a key insight of modern neuroscience [7] (PDF): Reasoning is actually suffused with emotion (or what researchers often call "affect"). Not only are the two inseparable, but our positive or negative feelings about people, things, and ideas arise much more rapidly than our conscious thoughts, in a matter of milliseconds -- fast enough to detect with an EEG device, but long before we're aware of it.

But my pop-up ad example illustrates another critical point: our susceptibility to bias is not static. We may be systematically biased, but we are also fickle. Our political behavior is surprisingly susceptible to context and framing. To some extent this should seem intuitive; our openness to new ideas can depend on our mood, on who is presenting the idea, etc. It has also been documented by numerous academic studies.

There is some evidence, for instance, that the location of the polling place has an impact on voting behavior, with those voting in schools more likely to support a tax hike to fund increased spending on education. A follow-up study confirmed that experiment participants shown pictures of schools were more likely to favor a proposed education initiative. Mooney cites another study that found that participants' acceptance of evidence for global warming differed depending on what sort of policy was presented as a solution. Personally, my favorite example of our susceptibility to priming is a study (admittedly with a small sample size) that found that the act of physically leaning left or right made participants more likely to agree with Democratic or Republican positions, respectively.

So we are biased, but fickle; What of it? This brings me back to the final lesson from my encounter with the pop-ups. Context can affect bias, and on the Web -- if I can riff on Lessig -- code is context. So why not design media that accounts for the user's biases and helps him or her overcome them?

There is some evidence, for instance, that "self-affirmation" exercises can limit our susceptibility to motivated reasoning. Our political beliefs reflect our conception of who we are and what we stand for. Therefore, information that runs counter to those beliefs threatens our perceived self-worth. Multiple studies have shown that having participants reaffirm their self-worth outside of politics reduces their vulnerability to motivated reasoning. (The exercises took the form of writing about a personal value unrelated to politics.)

How might I react if the pop-up at my friend's site prompted me to write a few sentences reaffirming my value outside of politics? Would I be more likely to read his posts with an open mind? Critiques of this example aside, my point is this: as we design ever richer media experiences for the Web, we should pay attention to this kind of research and consider how we might create media that draws on it to counter our political biases. Our ability to reason is flawed in predictable ways. And as we increasingly link our social graph into our media experience, there is plenty of relevant data to mine for hints of bias. Why not improve our reasoning using cognitively sophisticated media?

There are a couple of obvious criticisms that I'd like to note in closing. This research is relatively young and little is certain. But experimentation by media organizations could potentially help advance it by offering new data sets to further academics' understanding.

I imagine many people will dislike what they perceive as media organizations structuring content to manipulate them. But this already happens. As one young Silicon Valley guru recently put it, "The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads." And organizations like Fox News blatantly prey on viewers' biases to stoke fear and unrest. Plenty of time and money already goes into attempts to manipulate your beliefs and behavior; why not let responsible media organizations fight back?

Transparency is clearly essential to this kind of endeavor, and users should certainly have the right to opt out at any time. But isn't it worth a try? If I can watch a music video that takes place on the street I grew up on, why can't I read an article that adjusts to my biases?

Image: Wikimedia Commons.