Polluted water. Murky information. Public anger. Government promises of transparency and oversight to prevent a recurrence. And then, a short time later, it all happens again.

Watching the 840 square km oil slick now polluting China's Bohai Sea and listening to the excuses of the companies and officials involved, it is hard to avoid a sense of deja-vu.

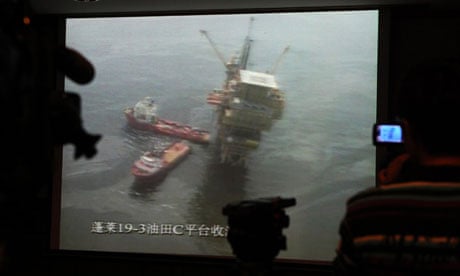

It has taken a month for news to emerge about the leak from a well in the Penglai 19-3 field operated by the US energy company ConocoPhillips in partnership with the China National Offshore Oil Corporation and .

The companies detected the problem on 4 June, but it only came to light on 21 June thanks to a microblog leak rather than an official release. After initially downplaying the accident, the authorities finally revealed this week that it covers an area half the size of Greater London.

The State Oceanic Administration (SOA) said on Tuesday that the seabed leak is the first of its kind in China and the water quality in the affected area has fallen to the lowest of its four categories.

Information remains sketchy. Neither company has responded to The Guardian's request for details. Despite vague reassurances from CNOOC on Wednesday that problem is "basically under control", there has been no estimate of the amount of oil discharged or the potential impact on marine life and coastlines. The government also revealed that the maximum penalty for such incidents is 200,000 yuan (£19,000). Compensation is likely to be considerably higher.

Xinhua, the state newswire, has blamed the US oil company for the leak and quoted officials who claimed the slow release of official information was due to "technical limits".

But the English language Global Times, which appeals to an international audience, boldly asked whether relations between government regulators and industry were too close.

"We cannot help but wonder: Is the SOA a serious watchdog that exists to prevent bigger incidents from happening, or a loving parent who is over-protective of his own child?...It is not acceptable that the SOA, which had learned about the incident in early June, held the news until a month later.

The Economic Observer, one of China's feistiest publications, accused China National Offshore Oil Corporation of hiding the accident in an act of "savage public relations".

Bloggers and environmental groups have been up in arms. Li Yan of Greenpeace said the authorities have failed to leans the lessons of pipeline explosion in Dalian last July.

Then as now, the environmental impact of the accident was initially downplayed by the authorities, but it was later recognised as China's worst known oil spill. Greenpeace claimed the scale of the leak was 60 times greater than reported.

The deja-vu is global. Industrial accidents and cover-ups happen all over the world. As my colleagues reported this week, there were more than 100 unpublicised oil and gas spills from European and American wells in the North Sea between 2009 and 2010.

China also has a dark history in this regard. I am particularly reminded of the botched cover up of the 2005 benzene spill into the Songhua river by the China National Petroleum Corporation.

Company executives and local government officials insisted at the time that water supplies were contaminated. As the toxic slick flowed towards Harbin, millions of residents were initially told their water supplies needed to be cut for several days for "routine pipe maintainance".

This was exposed as an outrageous lie, provoking a short-lived media outcry and promises of regulatory reform. Six-years on, not much seems to have changed. The authorities and state-owned oil industry are just as close, and their first instinct still seems to be to plug the news before the pollution.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion