In the mid-1970s I worked in one of the first Sam Goody record stores. Back then Sam actually owned the places and we carried a lot of obscure, off-label classical content. One day someone phoned in to ask if we had a particularly rare item. We talked about what she wanted for a moment, and I complemented her on her taste.

"Thanks, but please, could you hurry?" she anxiously interrupted. "This is a long distance call!"

I put her on hold, rushed through the shop to find the item, then jotted her name down and put the 33 rpm record at the front desk. She hung up without saying thanks or goodbye. I took no offense. In 1974 a residential long distance call through AT&T's monopoly network was an act of economic courage for most middle-class people. The first three minutes could run as high as $12, $4 more per each additional 60 seconds. If you wished your mother happy birthday too many times, you could end up in the hole for $20—the price of a night in a decent disco era hotel.

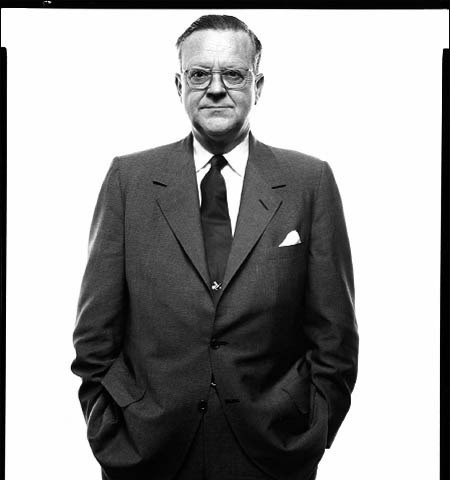

But help was on the way. The knight-in-shining-armor was Bill McGowan, brash son of a Pennsylvania railroad engineer and now Chair of an obscure company called MCI Communications Corporation. A venture capitalist, McGowan saw gold in cheaper long distance calling through microwave radio stations. Only one problem—MCI needed Federal Communications Commission permission for the operation, something that AT&T fiercely opposed.

MCI's case against AT&T quickly wound up in court. The Department of Justice had joined the foray by the same year that I took that classical call. The huge affair eventually turned MCI into "a law firm with an antenna on the roof," as its staff joked. But by 1984 Ma Bell agreed to divest into regional parts, and McGowan became the closest thing America has ever seen to a telecommunications hero.

The David-versus-Goliath version of the story is nicely told in a new documentary, Bill McGowan: Long Distance Warrior, which will air on public television stations on September 13 at 8pm EDT.

No business as usual

Some background: In 1969, the FCC ordered AT&T to allow MCI to stream through AT&T's basic phone network. MCI started out as a St. Louis-to-Chicago microwave operation for trucking companies. A St. Louis based MCI client would first use an AT&T phone to link to Chicago. The conversation would go through various AT&T lines, stations, and big switching offices, but then sign off AT&T's network just before it got to one of Ma Bell's "Long Lines." Instead, the call would hop onto an MCI microwave tower and fly the friendly skies to Chicago. Once there, it would again hitch rides with AT&T to its final local destination.

MCI distinguished this from long distance by calling it "private" or "business" service, a strange AT&T monopoly-era technical distinction that the FCC accepted. But the man who wears the black hat in Long Distance Warrior hated it anyway. AT&T Chair John deButts bitterly called the practice "creamskimming." To be fair, he was right. Under this arrangement, MCI got to market the priciest product that phone service offered, without having to share any of the costs of the dozens of local phone networks that it would depend upon to complete calls.

But to be fair to McGowan as well, since AT&T had pretty much wiped out any competition in local phone service, it had only itself to blame for this condition. That wasn't the way deButts saw it, of course. He truly viewed AT&T as a "natural monopoly," the concept enshrined in AT&T visionary Theodore Vail's Progressive Era motto: "One system, one policy, universal service."

More expensive long distance calls subsidized local connectivity, deButts claimed. This was the formula that supposedly made universal service universal. MCI represented a threat to that delicate balance, AT&T's wise men proclaimed.

Both ways

And so McGowan was informed by AT&T attorneys that in exchange for access to the Bell network, MCI would have to comply with a "capital contribution" plan to help with upkeep. 'How much would it be?' McGowan asked. deButts and his staff took their sweet time coming up with the details of the arrangement.

Finally McGowan's limited patience wore thin. Already plotting his antitrust suit, he met with the great man in 1973 at AT&T's New York City HQ. The exchange is recorded in Steve Coll's classic account, Deal of the Century: The Breakup of AT&T. By then, on top of the capital contribution demand, AT&T had also strategically dropped its long distance/local "Hi/Lo" service prices for customers along anticipated MCI routes.

"You can't have it both ways," deButts lectured McGowan. "You can't have competition and expect the existing rate structure to continue."

"But if you're trying to beat competition with Hi/Lo, the rate filing is premature," McGowan protested. "We haven't even started."

"We can't wait until competition has taken our business away," deButts retorted.

As McGowan described how MCI planned to expand its private line operations, deButts showed his hand. "In no way to do we think it's fair for MCI to compete in the switched telephone business," he insisted. "That's just wrong."

McGowan began to shout at deButts. "I have plenty of money," he warned—all of it borrowed from banks, of course. "I can spend it on litigation, or I can spend it on construction. I would prefer to spend it on construction."

"I've heard threats like that before," deButts furiously replied. "I won't be coerced... We will do what we have to, but you will find that we won't be coerced by threats of lawsuits."

As McGowan stormed out and the elevator doors closed, AT&T's Chairman turned to his attorneys. "Nothing about MCI can be treated as business as usual," deButts ordered.

24/7

Shortly after that standoff, a court issued the first opinion in favor of MCI's bid for access to AT&T's local phone system, which the latter telco appealed. But Long Distance Warrior's strong points are its portrayal of McGowan's chain-smoking, workaholic personality, and his successful assault not just on AT&T's monopoly status, but its public image as the quintessential benevolent corporation.

McGowan lived in a hotel just a few blocks from MCI's main Washington, DC digs. His staff had to beg him to buy some decent suits when he testified before Congress. When he finally married, it was to another entrepreneur, who lived in another city. Theirs was a happy commuter marriage.

MCI's boss also went out of his way to create a very different culture than AT&T's cradle-to-grave loyalty ethos. The company sported an unstructured, entrepreneurial atmosphere which favored new ideas over established procedures. Employees came and left the firm on a regular basis—anathema at AT&T, whose handbook went to so far as to instruct workers how to sit in their chairs.

In 1975, MCI unleashed its atomic bomb: Execunet, which McGowan told the FCC and Congress was just a more involved version of its "private" or "business" offerings. Although an Execunet call began by dialing a special MCI number, the innovation more aggressively exploited AT&T's local lines and switched exchanges. Execunet sounded like a exotic business service, but was really a long-distance product, poised to enter the residential market.

AT&T frantically warned that Execunet would destroy its subsidized relationship between long distance and local rates. When the FCC realized that McGowan had sold the agency a story, it declared MCI's new innovation an unlawful tariff. "Latent in the FCC's response was the anger of its staff and commissioners that MCI had deceived and betrayed them," writes the telecommunications historian Alan Stone.

The documentary doesn't get this deep into the legal weeds, but MCI went to court again and convinced a federal judge to overturn the FCC's move. Now AT&T found itself at the mercy of its greatest fear—a capitalized, technologically savvy competitor offering cheaper long distance telephone rates. In the public relations war that ensued, deButts insisted that MCI's service would ultimately hurt consumers via "degradation of service and higher costs."

Just paying too much

Not surprisingly, consumers found this line of reasoning unbelievable, but were still intimidated by AT&T. MCI sought to overcome this fear with a sophisticated advertising campaign that tapped into the lingering feeling of guilt that subscribers felt spending money on long distance calls.

"There was this great guilt on the part of the public," recalls advertising executive Tom Messner in the film. "'Oh this phone bill is so high.' 'You shouldn't talk to your mother.' 'You shouldn't talk to your brother.' 'Why did you call that guy?' And they would go over the bill and they would assume that they were just... bad."

So Messner came up with a brilliant TV spot that showed a woman making the same call via AT&T and MCI on a split screen—the cheaper MCI call tracked by the second. "You haven't been talking too much," the advertisement gently counseled while displaying MCI's telephone number. "You've just been paying too much."

As everybody familiar with this era knows, eventually AT&T realized that the deButts model was finished. The corporation settled with Uncle Sam, keeping its long-distance network and gaining the right to go into the computer business. MCI grew into a $9.5 billion telecommunications contender. It offered the first early commercial e-mail service, and pioneered in mobile and fiber optic technology.

But neither deButts, McGowan, nor his creation lasted a lot longer than AT&T's January 1, 1984 divestiture. deButts died in 1986. By then, McGowan's 24/7 lifestyle had caught up with him. When someone asked whether the new MCI building would include a gym, McGowen thought he was kidding. "If you want some exercise, go climb a microwave tower!" he scoffed.

"I don't think Bill ever exercised," his nephew recalls in the documentary. "I don't think he ate very well. I think he worked all the time and he pushed himself really hard." Two years after the Bell breakup, McGowan suffered a massive heart attack. A heart transplant kept him going for five more years, until a second failure. He died in 1992 at age 64.

As for MCI, it had 30,000 employees when it fatefully merged with WorldCom in 1998. "It was the end of Bill McGowan's company," the documentary acknowledges. WorldCom's CEO Bernard Ebbers was eventually sentenced to 25 years in prison for accounting fraud, and the merged entity filed for bankruptcy. In 2006 the MCI network was bought by Verizon.

But McGowan appears to have concluded his life with no regrets about his driven personae.

"You have to have stamina," he told a public television interviewer in the 1980s. "Otherwise you give up. Otherwise you get turned. Otherwise you listen to people tell you things where, if you follow their advice, you won't do it. What you are listening to are those people's ideas about what they can do, not your ideas about what you can do."

Listing image by Image from a video still of WTTW Presents Long Distance Warrior

reader comments

38