In a request made on October 10 to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, Verisign outlined a new “anti-abuse” policy that would allow the company to terminate, lock, or transfer any domain under its registration jurisdiction under a number of circumstances. And one of those circumstances listed was “requests of law enforcement.”

The request, submitted through ICANN's Registry Services Evaluation Process on October 10, proposed a new malware scanning service for domains as well as a new Verisign Anti-Abuse Domain Use Policy. In the request letter, Verisign stated that its policy would help the registrar align with requirements ICANN is placing on new generic top level domains. “All parts of the internet community are feeling the pressure to be more proactive in dealing with malicious activity,” Verisign explained. “ICANN has recognized this and the new gTLD Applicant Guidebook requires new gTLDs to adopt a clear definition of rapid takedown or suspension systems that will be implemented.”

In part, the proposed policy was aimed at empowering Verisign to act quickly to take down sites that are harboring malware, launching phishing attacks, or otherwise being used to launch attacks across the Internet. The scanning service, which registrars would opt into voluntarily, would scan sites on all .com, .net and .name sites for “known malware,” and inform the registrar and the site owner when malware is detected. Verisign has been soliciting domain registrars to participate in a pilot of the program, derived from the company's Verisign Trust Seal program, since March.

But the request also asked for authority to take down sites quickly for a number of reasons beyond malware, including “to protect the integrity, security and stability of the DNS; to comply with any applicable court orders, laws, government rules or requirements, requests of law enforcement or other governmental or quasi-governmental agency, or any dispute resolution process; (and) to avoid any liability, civil or criminal, on the part of Verisign, as well as its affiliates, subsidiaries, officers, directors, and employees... Verisign also reserves the right to place upon registry lock, hold or similar status a domain name during resolution of a dispute.”

Verisign said it has been piloting takedown procedures with US law enforcement agencies, cybersecurity experts, US government Computer Emergeny Readiness Teams, and domain registrars to establish baseline procedures, and has begun planning pilots with European government agencies and registrars. Just what those baseline procedures are—and what recourse domain holders who run afoul of them have—wasn't spelled out. Verisign said it "will be offering a protest procedure to support restoring a domain name to the zone."

Aden Fine, senior attorney with the ACLU, said in an interview with Ars Technica that the "protest procedure" is cause for concern. "The default shouldn't be 'take down first'," he said. "Any time the government is involved in seizing websites, that raises serious First Amendment issues. It doesn't matter if it's a private company pushing the button."

Electronic Frontier Foundation media relations director and digital rights analyst Rebecca Jeschke told Ars Technica that Verisign's proposal is "an extraordinarily bad idea." "We've already seen how problematic domain seizures are through the ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) shutdowns," she said. "It's similar to things the US government is trying to get through congress with the Protect IP Act, though there's a little more oversight in Protect IP. The key is if you're going to do something as drastic as taking a whole site offline, you at least need some meaningful court review. "

Update: Verisign quietly withdrew the request on October 13.

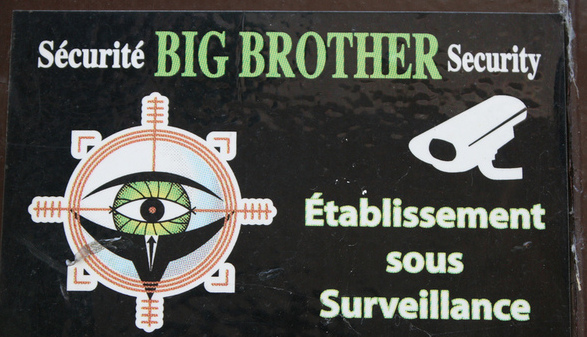

Listing image by Photograph by Quinn Dombrowski

reader comments

55