Here at Ars we're big fans of Creative Commons, both the idea behind it and the work that gets produced. As publishers, we benefit from Creative Commons in a number of ways—we look things up in Creative Commons-licensed Wikipedia (used with caution, of course), the Creative Commons-related policy issues that we cover give us a steady stream of great news content, and we make use of Creative Commons-licensed images in our news stories.

This last piece—the use of Creative Commons images—has historically been one of the trickiest issues for us to navigate as a publisher, given the number of different Creative Commons license types. Each Creative Commons license has its own set of restrictions, and, despite the fact that the license clauses seem fairly clear on the surface, it's not always obvious to us as end users what can be used where and for what purposes.

Note that this isn't solely a problem for sites like Ars and large publishing houses like Condé Nast. There are tens of millions of blogs out there, many of which derive some amount of revenue from popular sources like Google ads or Amazon's affiliate program, thereby blurring the line between commercial and noncommercial publications. These bloggers routinely dip into the giant Creative Commons image bucket that is Flickr, but it's a safe bet that few of them are rigorous about checking the licenses before posting.

If the blogging revolution has turned many of us into micropublishers, ad platforms like Facebook and Google, and e-commerce platforms like Etsy and eBay, have turned many of us into advertisers with something to sell. Creating Facebook or Google ads with images in them is easy and cheap, to the point that anyone with something to hawk online can become an advertiser. As is the case with blogging, anyone who wants to use Creative Commons-licensed images in their ads needs to be aware of the licensing terms and understand what's legit and what isn't.

Most of the guides out there for working with Creative Commons content, especially images, are for image makers who want to pick a license for making their own work available. Even the Creative Commons site itself is geared toward Creative Commons license users, and not Creative Commons-licensed content users. So as a small Public Service Announcement, we've put together this brief intro to Creative Commons image usage.

This guide is aimed at two types of users: 1) publishers big and small who want a high-level overview of Creative Commons licensing and the issues involved in sorting out what can be used where, and 2) advertisers big and small, who want to make use of Creative Commons-licensed images while staying in the good graces of content makers and end-users.

Creative Commons license basics

The first thing you should realize about either publishing images under Creative Commons or using Creative Commons-licensed images is that there isn't actually a special license category for images under Creative Commons. Rather, Creative Commons licenses are divided up into six main license types, and each one can be tweaked to cover text, images, video, and other types of works.

In order to understand the Creative Commons license types, it's best to take a look at them in terms of their clauses. Creative Commons licenses are defined by the presence or absence of four main clauses, detailed below. These clauses are mixed and matched to produce the four main types of creative commons licenses.

Attribution

All of the Creative Commons licenses have an Attribution requirement, which is simply a requirement that anyone who uses the work give proper credit to the work's original creator. For images, this usually means the name or handle of the author and a link back to the original site where the image was hosted (e.g., Flickr).

The Creative Commons wiki stipulates that, in general, proper attribution involves the following (emphasis added):

- If the work itself contains any copyright notices placed there by the copyright holder, you must leave those notices intact, or reproduce them in a way that is reasonable to the medium in which you are republishing the work.

- Cite the author's name, screen name, user identification, etc. If you are publishing on the Internet, it is nice to link that name to the person's profile page, if such a page exists.

- Cite the work's title or name, if such a thing exists. If you are publishing on the Internet, it is nice to link the name or title directly to the original work.

- Cite the specific Creative Commons license the work is under. If you are publishing on the Internet, it is nice if the license citation links to the license on the Creative Commons website.

- If you are making a derivative work or adaptation, in addition to the above, you need to identify that your work is a derivative work i.e., "This is a Finnish translation of the [original work] by [author]." or "Screenplay based on [original work] by [author]."

Most Creative Commons images come from Flickr, and if you find yourself using a lot of Creative Commons-licensed images from that site then you'll definitely want to know about ImageCodr. With ImageCodr, you paste in the URL of the image on Flickr, and it spits out a nice overview of that image's license along with some HTML for using in fully crediting the photo.

No Derivatives

A license with the No Derivatives option prohibits users from altering, building upon, or transforming the work. If you're going to use a Creative Commons-licensed work with this option, you must use it exactly as-is.

Of course, the No Derivatives option does not interfere with Fair Use rights, so you're free to do the usual parodies, excerpts, and the like. More subtle alterations, like cropping an image to make it fit your page width, might seem to be a gray area, but as long as you don't make enough changes so that your version, when taken as a whole, qualifies as an original, copyrightable work in its own right, then you should be safe.

If you're looking for a more in-depth discussion of how to safely use works that have the No Derivatives clause, librarian Molly Kleinman has a really excellent how-to on the subject.

Noncommercial

Many Creative Commons images have a noncommercial clause that restricts them to "noncommercial use." But despite Creative Commons' seemingly straightforward definition of noncommercial use as any use that is not "primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or private monetary compensation," there is a ton of confusion out there as to which specific uses are commercial and which ones aren't. Indeed, the definition of "noncommercial use" is so widely debated that in 2008, Creative Commons commissioned a 255-page report on how the online public understands and misunderstands the meaning of the terms "commercial use" and "noncommercial use."

There are any number of reasons why this particular clause has caused such a headache for Creative Commons users, not the least of which is the fact that the Copyright Act itself doesn't really make a distinction between these usage types (though they are important for some laws). And then there are the infinite number of vaguely commercial or noncommercial situations that a Creative Commons-licensed image could find itself in, from a corporate intranet to a non-profit fundraiser invitation to a personal blog that runs AdSense.

Given the amount of confusion about this term, there's no way we're going to try to cut through it, here. Instead, we'll give a few simple rules of thumb, depending on who you are.

1. For advertisers: You're probably not going to be able to get away with using a noncommercial Creative Commons image in an ad. If you have lawyers, you should definitely ask them for an opinion, because they may advise you otherwise, depending on the specifics of your particular case. If you don't have ready access to a lawyer, (e.g., you're an amateur throwing together something for a Google or Facebook campaign), then it's best to stay away from noncommercial images.

2. For editors: You really need to check with your publisher's legal department on this question, because putting noncommercial Creative Commons images in your articles is a real gray area. Some IP lawyers consider this to fall under Fair Use, while others do not. Which way a particular lawyer parses this question often depends on whether they're representing a big publisher, or an outraged Flickr user who's sending the aforementioned publisher a takedown notice.

3. For everyone else: In any given usage situation—regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or a nonprofit organization—the question you should ask yourself before using a noncommercial Creative Commons licensed image is "am I using this image to coax money out of someone else's pocket and into my own?" If the answer is "yes" (e.g., the aforementioned charity fundraiser invitation), then it's best to go with a noncommercial image.

Kleinman also has a solid intro to noncommercial use of Creative Commons works, although it's much more geared for the folks in category 3 than those in the first two groups.

Share Alike

The "Share Alike" attribute is intended to mimic the function of the GNU Public Licence's "copyleft" provision, and it stipulates that anyone who creates a derivative work has to license that work under the same Creative Commons license that you used for your original work.

Because this particular clause matters only to those who plan to make new, derivative works based on Creative Commons-licensed content, it's generally not that important for publishers, advertisers, and most end-users.

Mixing and matching

The six Creative Commons licenses are all combinations of the above four clauses. Each license has the Attribution clause, and then there are one or more other clauses added on to make a complete license.

At the least restrictive end of the spectrum is the Attribution license, which uses only the attribution clause. If a work has the Attribution license, then it can be freely altered and used commercially, and any derivative works can use any license; the only requirement is proper attribution. At the most restrictive end is the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license, which disallows both commercial use and derivative works.

Here's a full list of the license types, with basic descriptions adapted from the Creative Commons text:

Attribution: This license lets you distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon a Creative Commons work, even commercially, as long as you credit the maker of the original creation. This is the most accommodating of licenses offered.

Attribution-ShareAlike: This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon a Creative Commons work even for commercial purposes, as long as you credit the original maker and you license any new creations under identical terms. This license is often compared to “copyleft” free and open source software licenses. All new works based on your own derivative work will, of course, carry this same license, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use. This is the license used by Wikipedia.

Attribution-NoDerivs : This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to the original maker.

Attribution-NonCommercial: This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon a Creative Commons work non-commercially, and although any new works must also acknowledge the original maker and be non-commercial, you don’t have to license the derivative works on the same terms.

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike: This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon a Creative Commons work non-commercially, as long as you credit the original maker and license any new creations under the identical terms.

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs: This license is the most restrictive of the six main licenses, only allowing you to download the work and share it with others as long as you give proper credit, but you can’t change the work in any way or use it commercially.

All of the specific Creative Commons licenses that you'll encounter will fall into one of the above six categories. As you can probably tell from reading the descriptions, the licenses are constructed by starting out with complete freedom to use the work as a baseline, and then restrictions are added on via clauses. (Contrast this with normal content licenses, which start with the presumption of exclusivity and then add exceptions.) So if a license is silent on an issue, like commercial vs. noncommercial use, then you can assume that you're not restricted with respect to that issue.

Because of the way that the licenses begin with freedom and add restrictions, the Attribution-only license is the least restrictive, because its only requirement is that the licensee give proper credit to the original author of the work; otherwise, you're free to do what you like with the work. The last license on the list, the Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivs, is the most restrictive, since it includes the most clauses.

Finding Creative Commons images

After all of this talk of licensing, now comes the easy part: finding Creative Commons-licensed images that you can use in blog post, ads, news articles, and the like.

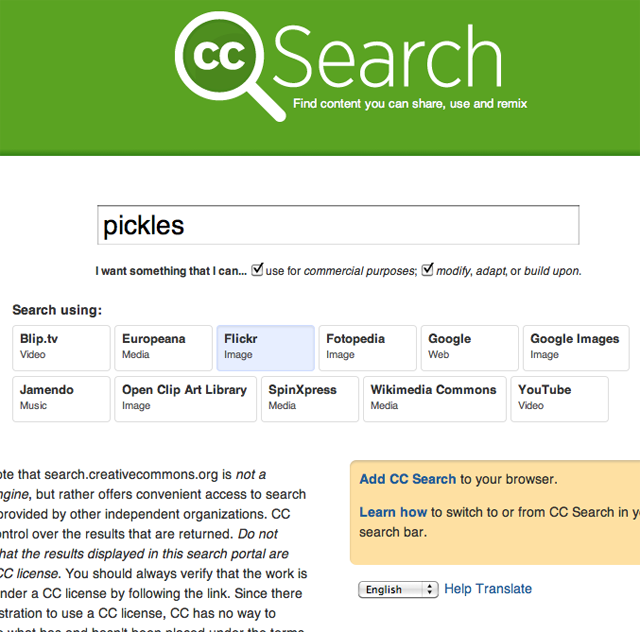

The first stop for any Creative Commons image search should be organization's own search engine. We recommend the beta search interface, which we've linked here.

You can select a source for images, click two filter options, and then get results from the aforementioned source.

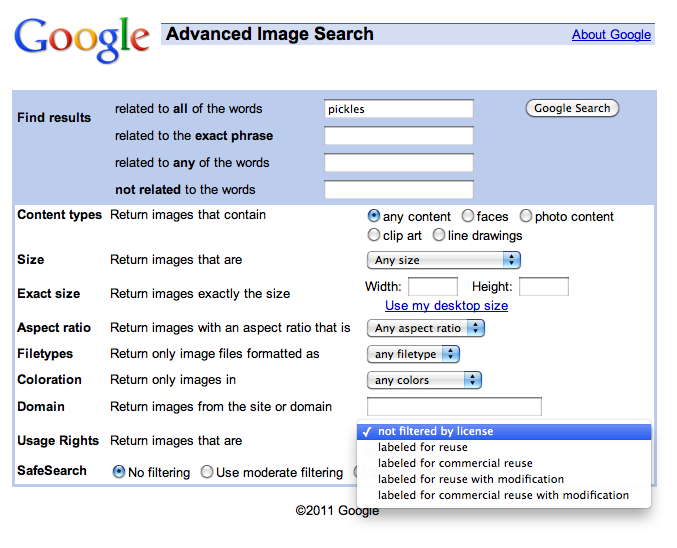

If you'd rather do things the old-fashioned way, both Google Images and Flickr have options for searching specifically for Creative Commons images.

With Google Images, you can go to the Advanced Search tab and filter results by license type:

On Flickr, you can either browse Creative Commons images organized by license type, or you can search within a license type for specific images.

With the tips and tools listed here, you should be well on your way to finding and using Creative Commons-licensed images in a way that keeps everyone happy—content makers, readers, and ad-viewing eyeballs.

reader comments

20