Story highlights

Satellites used to certify organic crops in Europe in pilot project

Partnership with organic certification company and European Space Agency

Satellites being used by farmers to water crops, protect environment

It’s not as futuristic as greenhouses on Mars, but farmers on terra firma are using space-based technology to certify organic crops.

Satellites have been used to prove that crops were fertilizer-free in a year-long project by Ecocert, one of Europe’s leading organic certification agencies, and the European Space Agency.

Instead of just detailed overhead photos, infra-red and thermal images and other data was collected and deciphered to gain a “spectral signature” of the crops and soil. From that Ecocert say they can determine if a plant is organically-grown or not.

The trials proved over 80% successful, according to Dr Pierre Ott of Ecocert ,and compared to physically going to fields to collect, test and certify them, much more time effective.

While the technology for organic certification needs to be improved – the Ecocert test only worked on wheat and corn grown in large fields – satellites are already sweeping huge swathes of the world’s arable land.

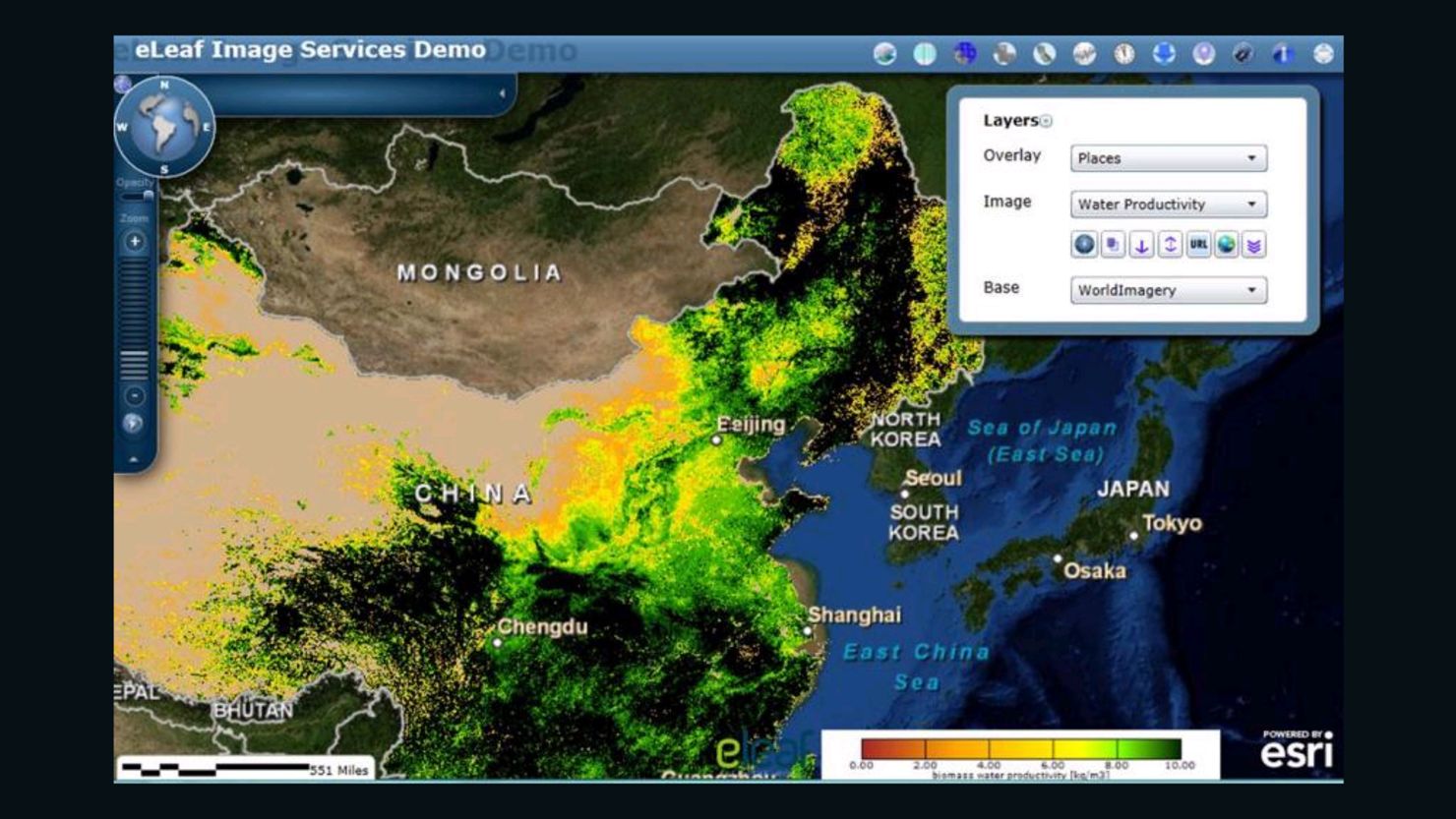

From Californian vineyards and Chinese rice fields to Colombian coffee plantations and Kenyan crops, satellites imagery is being used to monitor land and water use and promote environmental protection.

“Satellites have become commonplace in agriculture,” says Geoff Wade, director of natural resource industries for global information software company ESRI.

Originally used to calculate subsidies owed to farmers in the European Union, the technology has developed at a rapid pace.

“They are so good now,” says Wade “In the last few years six-inch imagery is commonplace. The level of detail of six-inch imagery on a field is incredible. People can genuinely use satellite imagery to fertilize correctly, or manage water stress.”

Through software developed by ESRI and applied by eLeaf, a company that supplies data on water use and vegetation, individual farmers and small-holders are able to get the benefit of the precise information about the state of their crops.

In an ongoing eLeaf project, funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development, farmers in Ethiopia, Sudan and Kenya are sent a text message on when to irrigate or fertilize crops.

Another project to promote environmental protection in South Africa measured the water consumption of natural vegetation compared to invasive species and agriculture for food production.

While the satellites and information technology are hugely expensive the cost of the information to the end users and farmers is not.

“Depending on the resolution of the images, it can be anything from a few cents to a few euros per hectare,” says Patrick Sheridan of eLeaf

There is still some way to go before satellites can take the place of farmers and be used to totally manage crops, water supplies and tell the difference between organic and non-organic crops.

The main obstacles to better and cheaper data are improving the resolution of images so more crops in smaller spaces can be analyzed, plus the revisit times of the satellites.

“But it’s still really good,” enthuses Wade. “You’d need lots of people to visit crops every week to do what a satellite can do.”

For Sheridan the biggest role satellite geo-information will have in the future is in providing data on water conservation and management.

“In a few years, we’ll have nine billion people living on this earth and in a lot of regions water is already scarce, but in about 50% of these people will live in water stress positions. We can tell governments ‘Are you doing ok?’ (in water management) or is there room for improvement, and that is really in quite high demand.”