Los Alfaques, a bucolic campground near the Spanish town of Tarragona, isn't happy with Google. That's because searches for "camping Alfaques" bring up horrific images of charred human flesh—not good for business when you're trying to sell people on the idea of relaxation. The campground believes it has the right to demand that Google stop showing "negative" links, even though the links aren't mistakes at all.

Are such lawsuits an aberration, or the future of Europe's Internet experience in the wake of its new "right to be forgotten" proposals?

Fireball

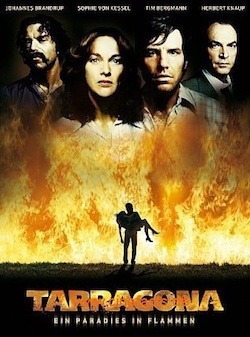

In 1978, Los Alfaques was the site of a horrific accident. A tanker truck carrying 23 tons of fuel left a refinery that morning and was driving to Barcelona in the summer heat. The truck apparently sprang a leak. As it passed the campground, a white cloud of vapor drifted from the road toward hundreds of curious campers. The cloud ignited without warning—carrying the fire all the way back to the truck, which exploded into a massive fireball. More than 200 people were instantly incinerated. (The episode became a 2007 movie called Tarragona: Ein Paradies in Flammen; many of the tourists at the camp were Germans.)

The tragedy happened through no fault of Los Alfaques, but it continues to dog the campground three decades later. A Google search for the camp brings up images from the aftermath, a Wikipedia article on the disaster, YouTube clips showing Spanish news accounts from the time, and more.

Last year, the owner of Los Alfaques, Mario Gianni, sued Google's Spanish subsidiary over the search results. As Spanish newspaper El País put it, this was because "potential users might lose interest in going to the campsite." A Spanish blog covering the case expands on the complaint. The search results "violate the plaintiff’s right to honor and damages its reputation. The complaint sought moral damages, as well as an injunction to stop showing those results."

The right to be forgotten

Spain has a tough set of policies regarding the "right to be forgotten," under which people can go to the courts or the country's data protection authority to demand companies delete various records about them. (For instance, Facebook might have to remove a person's photos from the Web if the person later wants them down). But this raises all sorts of thorny questions once it goes beyond a demand that some marketer remove your dossier from its database. What happens when you want to remove information from news accounts?

A rash of cases in Spain are now testing the law's limits, though few have been ruled on yet. Peter Fleischer, a privacy lawyer at Google writing in his personal capacity, noted last year that he understands some of the issues, but doesn't believe search engines should be forced to adjudicate them:

People who feel that information about them was wrongly published by these web sites can always ask them to correct or delete it. But newspapers and government websites usually have published this information legally, or indeed may even be legally obligated to publish it, or may be exercising their rights of freedom of expression. As search engine intermediaries, Google and other search engines play no role in what these web sites publish, or in deciding whether they should revise or remove content based on someone's privacy claim against them.

That's why I think it's wrong that the Spanish Data Protection Authority has launched over a hundred different privacy suits against Google, demanding that Google delete web sites from its index, even though the original websites that published the information (including Spanish newspapers and Spanish official government journals) published that information legally and continue to offer it. The legal question is important: should search engines like Google be responsible for the content of the web sites that they index?

The debate in Spain occurs against an unfolding legal backdrop. The EU introduced its own privacy update that includes a limited "right to be forgotten" last month. EU Commissioner Viviane Reding noted at the time:

"The right to be forgotten is of course not an absolute right. There are cases where there is a legitimate and legally justified interest to keep data in a data base. The archives of a newspaper are a good example. It is clear that the right to be forgotten cannot amount to a right of the total erasure of history. Neither must the right to be forgotten take precedence over freedom of expression or freedom of the media."

Legal scholars like Jeffrey Rosen remain skeptical that such a right won't lead to all sorts of problems for free expression. But in Spain, the debate continues. Last week, Los Alfaques lost its case—but only because it needed to sue (US-based) Google directly. Gianni is currently deciding whether such a suit is worth pursuing.

Listing image by Photograph by Daniel Garcia

reader comments

97