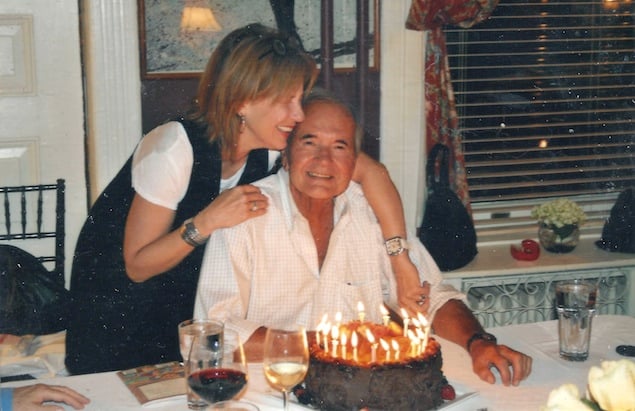

Nancy Doyle Palmer is a Washington-based journalist and screenwriter. Her work has appeared in Washingtonian, O: The Oprah Magazine, the Atlantic, and the Huffington Post. Her screenplay Sluglines is currently in development. John S. Palmer, a veteran news broadcaster for more than 40 years with NBC News, died in August, 2013, and his memoir, Newscatcher, was published this month. Here, Nancy shares their story.

I’m a new widow, so sometimes I’m oblivious. Like when Cat Stevens lyrics circle through my head—“And though you want things to last forever you know they never will…you know they never will”—all day long, and I don’t even realize it’s significant.

My husband of 31 years died a year ago last August, after a sudden 20-day stay in the hospital that, looking back, had all the elements of a slow-motion car accident. The immediacy of the transition was like having a baby—you go from being hugely pregnant to actual childbirth to being a new mother in the space of mere hours. But this time, like taking a series of photographs, I went from—flash!—high-alert nurse to—flash!—holding his face against mine as he quietly left us to—flash!—a widow.

So seamless that there is no pausing to be shocked. You just come out the other side.

The awkwardness came quickly, too. I spent the next week talking to pretty much everyone I had ever met—increasingly tall men and boys stooping over to hug me, me returning the embraces feeling hunched and clumsy. I find myself embarrassed when I am alone with men, a weird and adolescent humiliation. The crone feeling returns as I see myself, crying, in the mirror—hoping for a pretty tear-stained face, sweetly vulnerable, but greeted instead by a perfect rendering of Munch’s “The Scream.”

In my husband’s final days, the young man I married came back—he became thin again, his face unlined, an innocence of intent and heart restored as he became increasingly both less and more himself.

I find myself remembering all our lucky times, all the things that made us us, all the little ways we celebrated. We are the Palmers! We love the beach! We love Dalmatians and Jack Russell terriers! We have one, two, three little girls! We love their schools! We love Jeeps! We ski! We collect Limoges boxes to symbolize everything!

Moments of pure contentment come back in force: early autumn evenings, when I bring him a drink outside while he grills our dinner and we hug in quiet perfection as we listen to the hum of our children inside, the youngest belting out Disney songs up in her room.

That particular child, now 26, sat down next to me on my bed not long ago, half dressed for work, with her arm around me as I wept from the worst kind of dream, the kind that comes right before waking devastation—one where he was back and telling me it was all a mistake. She has his presence and her own grace as she sits quietly next to me.

I met him 35 years ago when he was in the midst of, yet seemingly oblivious to, his own grief. He’d lost his sister, his mother, and then his father, all while working overseas as a television news correspondent. He returned to the US to cover the White House; I was his production assistant. He invited me to be his guest at a luncheon hosted by President Carter for the King and Queen of Belgium. He later invited me to his home in Georgetown to watch 60 Minutes. He told me he loved me the first night we spent together. I chalked it up to so much loss, but worried when he stopped saying it so much. Then he proposed.

My gentle grief counselor advises meditation. We shut our eyes together, and she asks me to find him. He’s usually on a bench at the base of an improbably gorgeous tree, waiting for me. Something happens when I join him that I cannot yet describe or easily replicate, but something happens all the same. I don’t fear it or crave it; it’s elusive. Days or weeks pass before I even want to try to go there again.

My counselor tells me this kind of grief can be a beautiful journey. I accept the dare.

When I was little, I was afraid to spend the night out. My sole, disastrous venture into summer camp involved a daily visit to the director’s office to call home and beg my parents to come get me. The word homesick is one of the most apt in the English language. My long-dormant symptoms have all returned: the awakenings at dawn, the misty distractions that clear into hard truth, the sinking abdominal certainty that something is very wrong.

In the fall, I swim in our overheated neighborhood pool through November, escorted by my increasingly vigilant Jack Russell Terrier and her tennis ball. I start my laps in the warm water at dusk—earlier each day—pausing to look up at the tops of trees still shimmering in golden summer hues. Treetops are my heaven, and I know he is there. I know I will be going someday, too. Sometimes I wish it was soon.

I can’t count the times and places over the last 32 years that he sat by a pool while I swam laps, patiently waiting (okay, sometimes drinking and smoking) or throwing a ball for the dog over and over again. Now, though he’s not there when I check through my goggles, it’s still water where I find him. I swim in it. Can’t drink enough of it. It blurs my eyes.

In the last few years, he cried easily—often to the embarrassment of our daughters—talking about an act of decency or moment of applause, remembering Martin Luther King, President Kennedy, his father. His face would grow wet, and he’d use both fists to wipe his eyes. Sometimes I shared the girls’ impatience with this, but more often my heart welled as much as his eyes did.

Now mine are the tears that spring and sting, unbidden—at the craziest triggers, but most often because of my proximity to love, and love’s wonderful first cousin, kindness.

In the last week of my husband’s life, the doctors noted something called la belle indifference. It’s a phenomenon of naïve or inappropriate lack of concern about one’s illness or disability, also called a conversion disorder. I call it heaven.

In those final days, he was unaware he was terribly ill, that he had lost his sight, that he could barely breathe without machines, that he was dying. He was chatty, sociable, lively, and darling. His often-muted Southern accent was out in force. He was always holding someone’s hand. He knew all the news headlines. He put the chaplain at ease. When our oldest daughter had the idea to take turns reading aloud chapters from his unpublished memoir, he listened with his eyes fixed off in the distance, often finishing an anecdote or punchline along with us.

The night before he died, I drew a lounge chair close to his bed, and we recounted every beautiful hotel room we’d ever been in, deciding the Dolder Grand in Zurich was the very best. I’d drift off to sleep only to awaken to the alarm that signaled he’d removed his oxygen mask. It was like taking care of a restless child. He kept pulling off the mask as if to see something better—listening to someone’s call.

I don’t think his beautiful indifference was a hysteric reaction to the reality of his death so much as it was a choice. A dare.

My husband was a fine man—tender, kind, sincere, and very funny. The quality that always struck me the most was that he was brave. He demonstrated this often in his career as a war correspondent, in the face of danger, illness, career setbacks, but also as a fierce protector of his family and friends. He always went first.

The last day of his life, we gathered around him, and one of our favorite respiratory technicians, a young man named Taki, came in. He told us that while it might feel that we were losing him, we were, in fact, winners. Because we had so much love.

This is what I’ve learned: Love is an element as real and transformative as time and water, a force so powerful it is both the root of and the solution to grief. John’s graceful affect was his gift to us and our lesson to absorb.

The answer to understanding the loss of someone I loved wholeheartedly for most of my life came not in tears, trees, or memory but in simple math—an algebraic formula for my broken heart.

Nancy + John = Love

Nancy – John = Grief

Nancy + Grief = Love

Love is the answer. Love is all you need.

So when the refrain returns—the looping lyrics like Macy Gray’s “There is beauty everywhere” swirling in my head—I finally understand.

For more about Nancy and John, watch a clip of Nancy talking about her husband on the Today show this past Sunday.