The news that Apple was opening the iOS app-store to ad blockers for mobile devices created a storm in publishing circles, which meant that we heard a lot about them, because publishers publish things that are important to publishing.

Whatever happens with ad-blocking for iOS, the reality is that ad blocking has grown more prevalent, year after year, since the web’s beginning, and shows no sign of slowing. It’s only a matter of time until a major browser ships with ad blocking turned on by default. It’s also only a matter of time until one of the big-data brokerages fed by the advertising ecosystem has its own privacy Valdez and leaks toxic, immortal, compromising information all over the web at unimaginable scale, making the Ashley Madison dump and the Office of Personnel Management breach look minor by comparison.

At root is an intrinsically toxic relationship between the three parties to the advertising ecosystem: advertisers, publishers and readers. Advertisers buy publishers’ inventory to sell things to readers, but publishers sell inventory to advertisers because they want money, not because they want to help sell products. Readers want to read what the publishers are publishing. A tiny fraction of readers want to buy what the advertisers are selling, and this microscopic minority subsidises the whole operation.

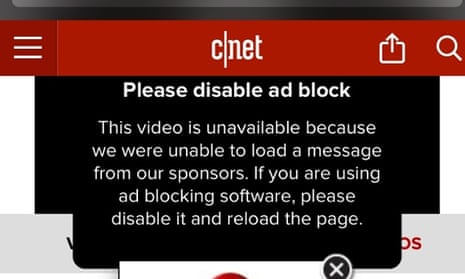

It’s easy to see the way this plays out for the worse. Unscrupulous publishers have made a practice of defrauding advertisers, spoofing the number of times their ads are shown in order to make more money from the same amount of readers. Advertisers have leaned on publishers to make ads more obtrusive – first with pop-up ads, then, after blockers became standard, with roll-downs, interrupters, pop-unders, ads that scroll with the page (eating your CPU in the process), and the whole parade of mutated attention-economy market-failures that fill your browser every day. Readers respond by installing ad-blockers, meaning that fewer readers are counted by the advertisers, meaning that the publishers get paid less and have to allow advertisers to serve more obtrustive ads in order to keep the money flowing.

The mistrust between advertisers and publishers has given rise to a fourth entity in this ecosystem: ad counters. These are companies that generously offer to independently count the number of times the publishers serve the advertisers’ ads – all the advertiser needs to do is tell the publisher to put the ad-counters’ “beacons” on their pages. Of course, ad counters aren’t charitable operations: they give away this independent counting function because it lets them gather titanic amounts of information about browsing habits. When you use Ghostery or Privacy Badger to examine a page and discover that a dozen (or dozens!) of companies are tracking your visit there, that’s this dynamic at play.

Ad counters are really data brokers and they’re incredibly profitable. The data is sold to marketers, to governments, and to consumer-research institutions. The only reason that data can be economically captured and aggregated is because advertisers don’t trust publishers, and insist on allowing ad counters/data brokers to act as trusted third parties to count ad-views.

The boom in ad-blocking technology is driven by three factors: annoyance at the content of ads; annoyance at the effect of ads in slowing computers to a crawl and worries about privacy. Advertisers and publishers can do something about the first two. In the early history of the web, pop-up ads climbed to a kind of terrible apogee before collapsing catastrophically because of audience pushback. Given enough pushback, advertisers will figure out ways to make their ads less obnoxious and less processor-intensive.

But the privacy concerns – always a minority issue, now a growing worry – are not so easy to address. Ashley Madison and the Office of Personnel Management weren’t the big leak-quake: they were the tremors that warned of the coming tsunami. Every day, every week, every month, there will be a mounting drumbeat of privacy disasters. By this time next year, it’s very likely that someone you know will have suffered real, catastrophic harm due to privacy breaches. Maybe it’ll be you.

Privacy-minded ad-blocking is only going to increase from here on in, because we have already shot past peak indifference to surveillance.

Here’s the dirty secret of ad blocking: it only works because advertisers don’t trust publishers. If stickyeyeballcontent.com serves ads from its own server, from stickyeyeball.com/images/, then any blocker that prevents those images from loading will also prevent the images that accompany the stories you want to read from loading, too. It’s not hard for publishers to serve their own ads, it’s just hard to get advertisers to believe that those ads have been counted accurately.

The answer isn’t complicated, it’s just hard. Arrive at a technical, economic and/or legal means by which publishers can be trusted to serve ads themselves, without the ad counters interposing themselves in the mix.

One possible solution that gets us most of the way there: a foundation-funded charitable trust, subject to reliable third party audits, that will count ads for anyone, anywhere, without collecting or retaining any personal information. Rather than having ad blockers review advertisers’ practices to decide which ads to block and which ones to pass, they could simply pass any ad that was counted by this “fair trade” trusted third party. Some advertisers won’t pay as much to reach audiences that can only be targeted by which sites they read (or possibly where they are physically located), but in a privacy-conscious future, it’s not a choice between targeting or not targeting ads. It’s a choice between reaching readers or not reaching readers, full stop.

A more elegant solution would be to find a way for publishers and advertisers to deal with one another directly, without any need for a trusted third party. That’s a much harder problem, though: if you don’t trust someone, you also shouldn’t trust anything that their computer tells you. Random audits and secret shoppers get you some assurance, but they’re clunky and inelegant.

A single, trusted third party is much more attainable. It has its own pitfalls; a hacker for a government or criminal enterprise could learn a lot about the whole world by comprimising such an entity. It would also be a litigation target –anyone who disliked any ad-supported website would militate to have his adversary struck from the list of trackable publishers, depriving the enemy of income to fight back with.

If it were a matter of business-as-usual or something as weird as a charitable web-tracker, I’d bet on business-as-usual. But the one thing I’m sure of is that business-as-usual isn’t an option, and it never will be again.