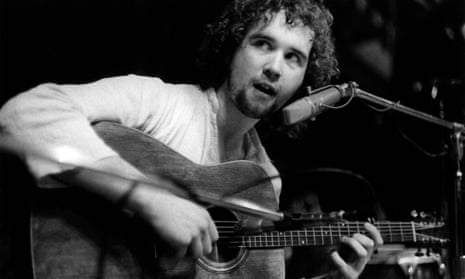

To many of those familiar with his work, John Martyn exists in the memory as the angel-haired, soulful-eyed hippie whose honeyed slur of a voice turned his ballad “May You Never” into one of the anthems of the 1970s singer-songwriter generation. Others will recall his innovative guitar playing, which evolved from standard folk-style fingerpicking into electronic storms of ecstatic improvisation. A seductive sweetness and a blazing creativity in his music reflected genuine aspects of his character. Yet, as virtually everyone who knew him could attest, he was also a dangerous presence whose propensity to inflict mental and physical cruelty brought tragedy to the lives of his women and children. The last but one of his long-term partners had an answer not available to all of them: “He could be quite violent, but it didn’t affect me because I used to do kickboxing before I met him. He never landed a punch on me.”

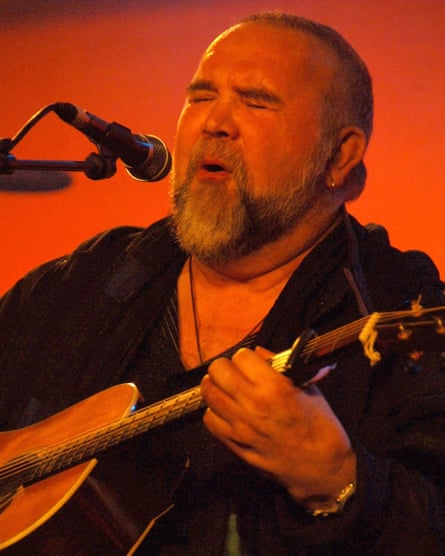

Martyn died in 2009, aged 60, six years after an untreated infection led to the amputation of his right leg. His body weight rose to more than 20 stone from the long-term effects of the alcohol and drug abuse that ran alongside and effectively derailed his career. Had he died in 1975, already with his best work behind him, he would have been welcomed alongside his friend Nick Drake into the “27 club”, reserved for musicians of that age and generation – others were Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison – who fell victim to the same arc of success and drug-taking. Instead he survived long enough to be cherished by a hard core of admirers and to become the subject of attempted career revivals that usually foundered on his own unswerving gift for self-destruction. It is the job of Graeme Thomson, the author of this excellent and necessary biography, to make sense of a tangled and often distressing story, in which the scales are balanced between pristine beauty and damage both primary and collateral.

Born Ian McGeachy in Surrey to a pair of light-opera singers, the boy who became John Martyn was brought up in Glasgow by his Scottish father and grandmother after his English mother left the family when he was two. It is not hard to imagine the “big dark hurt” that his sometime friend Ralph McTell identified in Serena Cross’s 2004 BBC documentary, Johnny Too Bad, beginning right there. Throughout his life Martyn would slip between conversational voices: Clydeside brawler, East End hard nut, Jamaican rude boy and caricatured RP, never inhabiting one of them for long enough to have his escape route blocked.

At 18 he was in London, leaving behind a fiancee as he started to make a reputation in the folk clubs, learning from Davy Graham and rivalling the likes of Bert Jansch and John Renbourn. A long-haired folk singer named Beverley Kutner, already tipped for a promising career, became his first wife. He travelled with her to Woodstock, where she was to make her first album, and hijacked the project: the LP was released under their joint names. She already had one child; soon she would have two more with him, finding herself relegated to the kitchen while he forged ahead.

Developing a highly personal musical language after adding amplification and a variety of effects to his guitar, he enjoyed the early patronage of two influential men: the record producer Joe Boyd, who soon left, and the boss of Island Records, Chris Blackwell, who gave him years of backing while making allowances for his waywardness. Many other admirers within the music business shied away, alienated by a nature that could switch from rogueish charm to outright threat in the time it took to drain a pint glass. “He was almost like a bomb that was going to go off,” the singer Claire Hamill, his lover in the 70s, says.

In pieces such as “Solid Air”, “Glistening Glyndebourne” and the extraordinary “Small Hours” (layering his guitar over the dawn sounds of the wind and the birds on the lake outside the Berkshire farm where he was recording), Martyn showed himself to be both an innovator and a poet. The looseness and spontaneity of jazz and country blues were perfectly blended with strong echoes of English pastoralism. Thomson correctly identifies his sublime 1974 recording of the traditional song “Spencer the Rover” as a pinnacle of his career, not least because its narrative of a rambling man dreaming of home and heart corresponded so exactly with the singer’s own fantasies. Efforts to turn him into a shiny rock star in the 80s and 90s were an insult to such work.

An encounter with Martyn in his final years gives the book a dramatic opening sequence. As well as displaying a love and understanding of his subject’s finest music, the author is clear-eyed about the regular bouts of “loud, stupid behaviour, intimidating and graceless”, the chaotic tours, the vast amounts of drink and drugs, the selfishness and the emotional cowardice. Yet amid the despairing shrugs of the surviving witnesses, including his abandoned partners and children, a love of the roaring boy shines through.