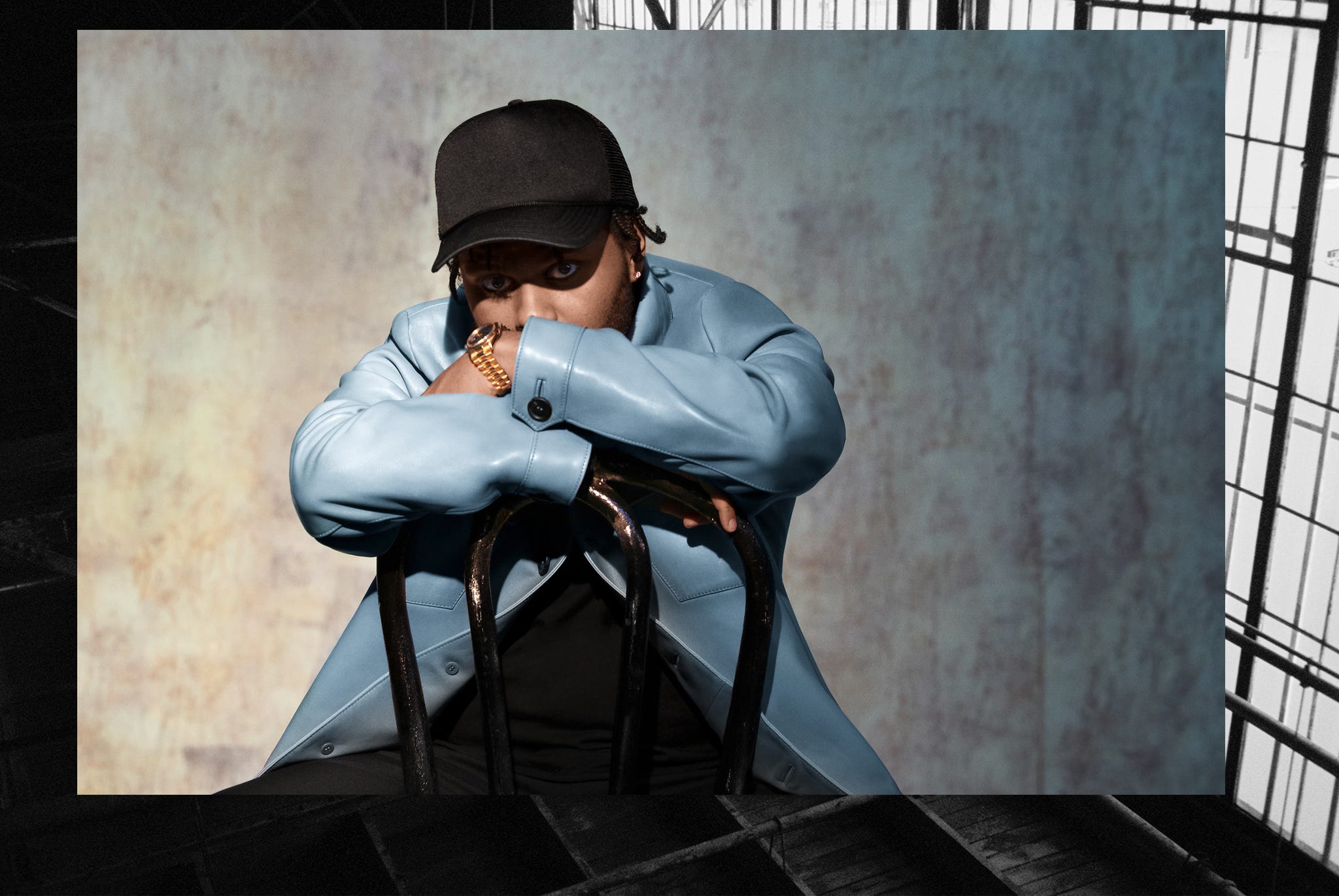

Abel Tesfaye, aka the Weeknd, is doing something few people are letting themselves do right now. Something we’ve been avoiding for the past four or so months. It’s thrilling, but a little dangerous even, considering how quickly the slippery slope could give way to an existential spiral. He’s sitting alone in the Westwood condo where he’s been holed up since March, imagining what he’d be doing right now, on a typical summer night on tour, in an alternate timeline. One that doesn’t include a pandemic and varying degrees of lockdown and social isolation. He really shouldn’t, but he’s letting himself be seduced by the hypothetical.

It’s 7:00 p.m. in L. A., where he is, but 10:00 p.m. on the East Coast, where, if it were normal times, he’d be making a stop on the tour for After Hours, his new album—which happened to drop on March 20, the same week the gates of hell fully swung open here on earth. If that hadn’t happened, he’d be backstage, getting ready to perform before a twenty-thousand-person crowd at Boston’s TD Garden. He’d have warmed up the band, and maybe now he’d be taking a preshow shot, or just swapping jokes with his crew right up until the moment the lights dimmed and he could hear the crowd, feel that little surge of energy he always gets right before he launches into the first song. He can’t really describe it, but he’s feeling it right now, like the tingle of a phantom limb. “I feel like my body was programmed and clocked to be onstage,” he says with the wistfulness of someone describing mislaid plans with an ex. The show—the whole tour—was going to be bigger, grander, more ambitious than what he’s done before. He and his team had imagined a theatrical experience, like a three-act play or a rock opera telling the story of the character from the “Blinding Lights” video, a bloodied, beat-up man in a sharp red jacket, desperately trying to fuck, drink, drug (maybe murder?) his way out of heartbreak and into emotional maturity. It would be a new iteration of the Weeknd, one that would take him into the second decade of his career. If the concept for Starboy, his last major tour, was all about interaction with the audience—as he puts it, “getting them to play along and sing along and jumping with them, you know, mosh pitting”—then this tour would be about distanced storytelling. Not intimacy with the crowd or letting the fans get close to him but letting them witness an experience he’s created. Less symbiotic, more parasitic. “The audience wouldn’t really exist to me,” he says. “I’d be in my own world.”

At least some part of Tesfaye’s plan came to fruition. He’s in his own world, just in an inherently disappointing expectations-versus-reality version of it. With nowhere to go tonight, he’s hanging out on Zoom with me. He signals his entry with a tentative “hello” that floats up from behind all of the open tabs I have blocking the window (an aspirational shopping cart from the Need Supply sale, several articles about safe sex in the pandemic, Twitter, Billboard charts, Wikipedia pages, etc.).

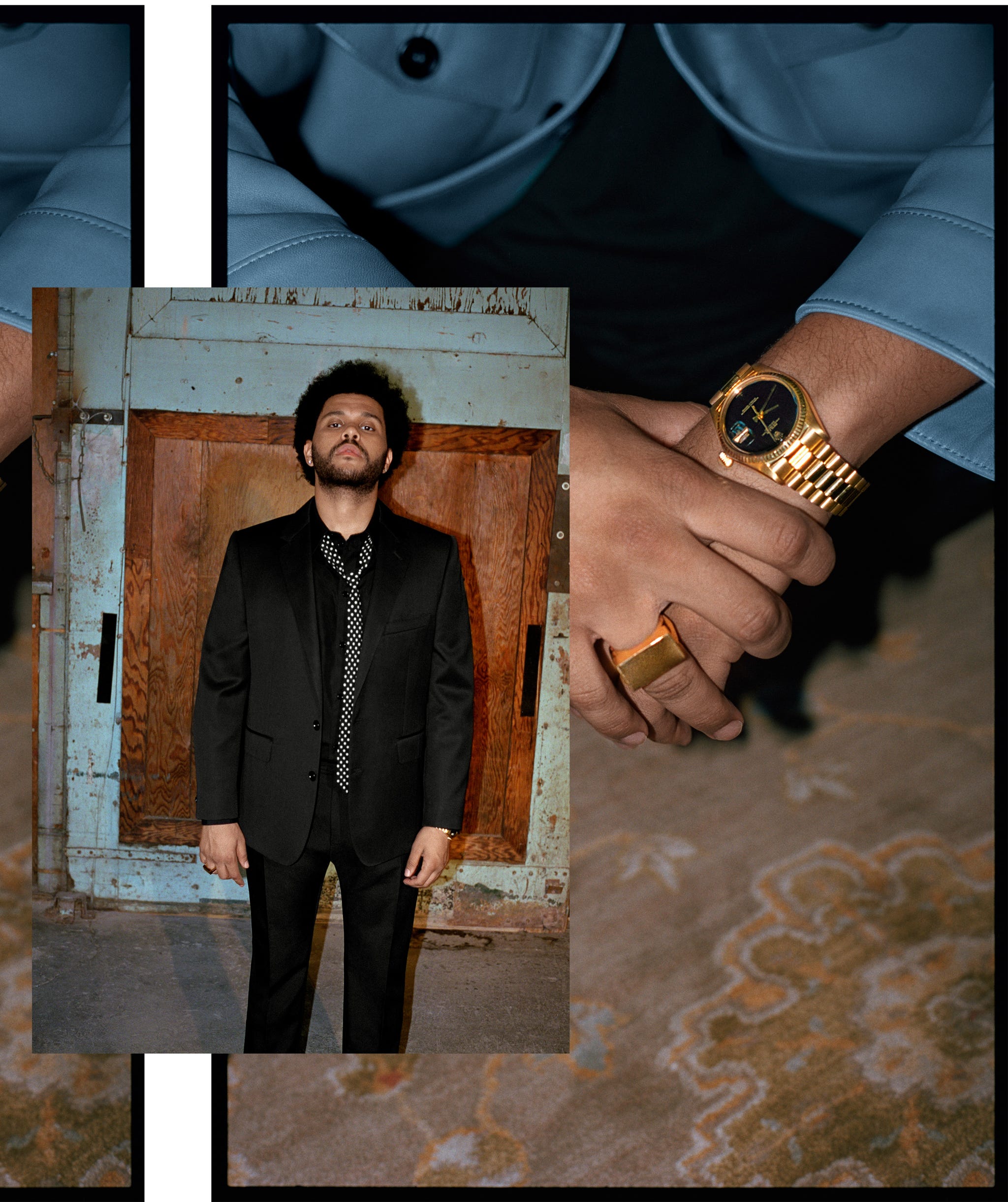

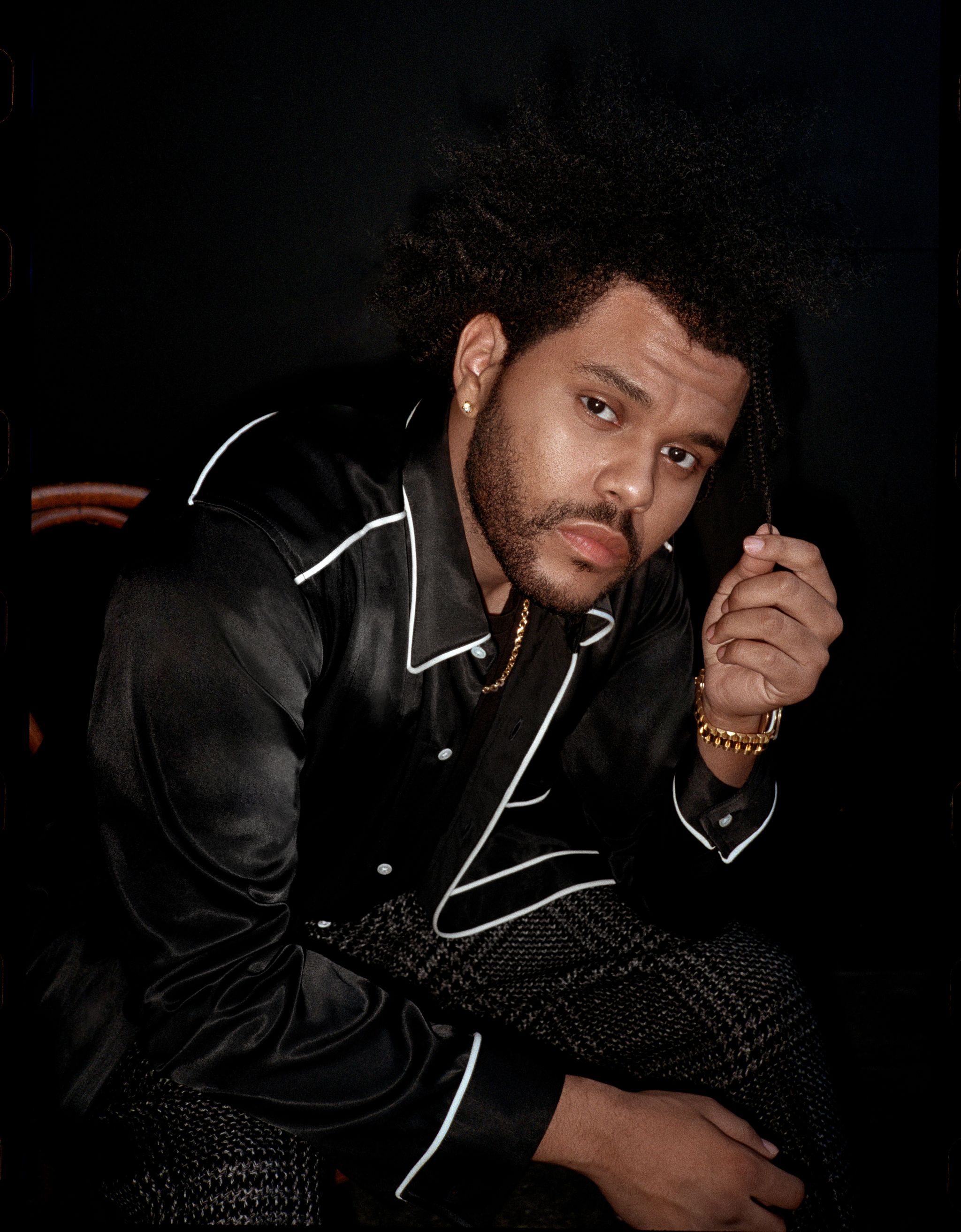

A few clicks and there he is, just a black-T-shirted torso at a desk, his Afro still shaped up like he hasn’t missed a barber appointment, a diamond stud glinting in each ear. (He’s long since cut off the hair writers used to spend paragraphs breathlessly describing.) He’s in early-evening L. A., and I’m in New York, a fact he apologizes for by making sure to close the blinds so I don’t get jealous of the sunlight still streaming through his windows.

“I’ve been trying to figure this out for the last ten minutes,” he says by way of greeting.

Hasn’t he been living on Zoom like everyone else?

“Yes,” he responds sheepishly, “but I usually have somebody just, like, set it up for me and I just come in. Today, I’m solo dolo.”

All incoming information about Tesfaye, from his publicist, from every profile of him ever written, indicates that he is incredibly shy. (This is always revealed as though it’s something that’s never before been said about a famous person.) He emerged on the music scene as a shadowy figure, so good at obfuscation that people didn’t know if the Weeknd was a solo artist, a group, or a computer projection. The debate over whether he really is just this shy or is committed to a bit and is actually some goofy, loudmouthed extrovert has been fodder for magazine profiles since he became famous—like really, really famous—sometime in 2015. Five years later, he’s won Grammys and American Music Awards, he’s headlined Coachella, he tours constantly. He goes to fashion-week parties and has had two high-profile, blog-analyzed romances, with a supermodel and a mega pop star. He’s worth tens of millions of dollars. The Weeknd has taken on a life of its own; it’s a character separate from the man who inhabits it. But the expectation is still a shy, taciturn Tesfaye. As his persona as a performer evolves, there’s a growing disconnect between who he is onstage and in his music and what he lets fans see of his personal life. It’s hard to tell if he’s trapped himself in a creative prison or if he’s created a handy line of defense for himself.

In an attempt to meet him where he’s at, we’ve agreed to start off discussing the five songs that he thinks define him, like we’re historians studying the past to provide insight into the clusterfuck of modern times.

He prepared his choices before our interview, dispatching his publicist to send the list over a day early, like a dutiful student. And when the getting-to-know-you talk—in which I am, disappointingly, not invited to tour the condo—leads to the specifics of the songs, he perks up, his round face and cheerful, dark eyes a jarring contrast to the lyrics his publicist sent me, full of “ooooh yeah”s, models, and pussies.

The first song is “What You Need,” from his debut mixtape, House of Balloons, a narcoleptic dream dirge on which he asserts, over and over again, that he might not be what you want, but he is what you need. The song came out in 2011, when his hair was growing into his famous Tim Burton-esque locks and he was folding shirts at a Toronto American Apparel. “Would you identify as a blipster?” I joke (I’m trying here), using a term that no Black person would use about themselves unless they were a masochist or a profound dweeb. He laughs and keeps going with the story. It’s one he likes to tell about himself: He had dropped out of high school, had moved out of his mother’s house in the Scarborough area of Toronto, and was living in a house with his friends in Parkdale, a grimy, cool neighborhood where he could throw parties, fuck around, take a cocktail of drugs, whatever. He was also composing songs, at first writing what he thought would be hits for pop artists to sing. But though he would soon help write songs for Drake’s 2011 album, Take Care, he couldn’t help but notice that he sang his songs better than other people.

Tesfaye says he was writing the music he wanted to listen to at the time. He was sick of sped-up EDM and figured if he wanted to hear slowed-down music from a sadboy who fucks, others probably wanted—no, needed—to as well. He takes his due for propelling that shift in the music landscape.

In a recent Variety interview, he pointed out how similar Usher’s 2012 single “Climax” is to his own early music, recalling the first time he heard it and sensing that it was directly inspired by his unique sound. He mentioned he found it flattering but also got “angry.” (“Climax” producer Diplo later confirmed that he was indeed influenced by Tesfaye’s early stuff.) The comment got an indirect response from Usher—a video of him performing the falsetto acrobatics the song requires—and launched #ClimaxChallenge on Instagram, which entertained people for a few days, as did the whisperings of a feud between the two performers.

But it wasn’t a feud, Tesfaye says, annoyed that anyone thought otherwise. “I hit him up to apologize and tell him that it was misconstrued. He’s one of the reasons why I make music. Definitely. No, no, I have nothing bad to say about Usher. The sweetest, most down-to-earth guy ever.”

Sometimes he played his own music on American Apparel’s stereo system. Everyone was feeling it, he says, but nobody knew that they were folding stretchy miniskirts and tube tops right alongside the guy who was on the store’s speakers. In time, House of Balloons, along with his subsequent 2011releases, Thursday and Echoes of Silence, became cult favorites. Fans responded to his indie-R&B Jordan Catalano vibe, and the recalcitrance became part of the allure.

It wasn’t an act, he says, or a gimmick. He just didn’t like the limelight. “I wasn’t too confident with how I looked. I didn’t think that I could sell the music looking like me,” he explains. He didn’t put his unobscured face on his album covers and wouldn’t talk to reporters. “I was very hardheaded. To this day, I don’t think I’ve ever done a radio interview. I just feel like I would give a horrible interview.”

He had no doubts that the music itself was good, however. Like, good enough to sell out amphitheaters and stadiums, so that’s where he set his sights as an artist. Could it be that his veneer of bashfulness was in service of that grand ambition? In a 2015 Rolling Stone interview that doubles as his oracle, Tesfaye told the reporter, “I think that’s why my career is going to be so long: Because I haven’t given people everything.”

So “What You Need”—what does this song mean to him? Is it about hiding in plain sight? The fear of owning his full power as an artist? What’s the meaning of need when it comes to artistry?

“No real meaning. Just a sexy R&B song.”

The sound he introduced on his first three mixtapes, which were later repackaged and rereleased as Trilogy, earned him a record deal and his first studio album, 2013’s Kiss Land, along with that cult following. It’s from Kiss Land that he chose the second song in his five-tune biography, “Wanderlust.”

I ask him what it felt like to experience a new rush of fame. What was going on emotionally back then? He doesn’t remember the exact emotions he was feeling.

At the time, he told Complex the song was about touring, and about not quite knowing who he was as a person, and about an honest-to-God fear he was having (it was inspired by horror-movie makers like John Carpenter) regarding fame. “Wanderlust” has the feel of a transition song: We hear hints of the poppy, synth-heavy anthems to come, but it clings to that House of Balloons sound. It didn’t not work, but it didn’t quite work, either. He realized a few things after that: He wasn’t much of a performer and needed to tour more, and if he wanted to sell out twenty-thousand-seat arenas, he needed some help engineering a pop song.

He asked the studio for guidance. The next three songs he chose as defining songs (a cheat; he tried to sell them as one choice by using slashes)—“Love Me Harder,” the duet he performed with Ariana Grande in 2014; “Often,” from his second album, 2015’s Beauty Behind the Madness; and “Earned It,” from 2015’s Fifty Shades of Grey soundtrack—were the result. The difference between “Often” (a platonic Weeknd track) and the other two (one a pop anthem helmed by the legendary Swedish hitmaker Max Martin and the other a radio-friendly track for moms who love softcore) shows how he was studying. How he was trying to take what worked from his stuff (i.e., endless synonyms for the way the female anatomy responds to his sex appeal and complicated feelings around disrespectful hookups) and make a hit. He did: It was the first time he’d ever heard multiple songs of his on the radio in rotation at the same time.

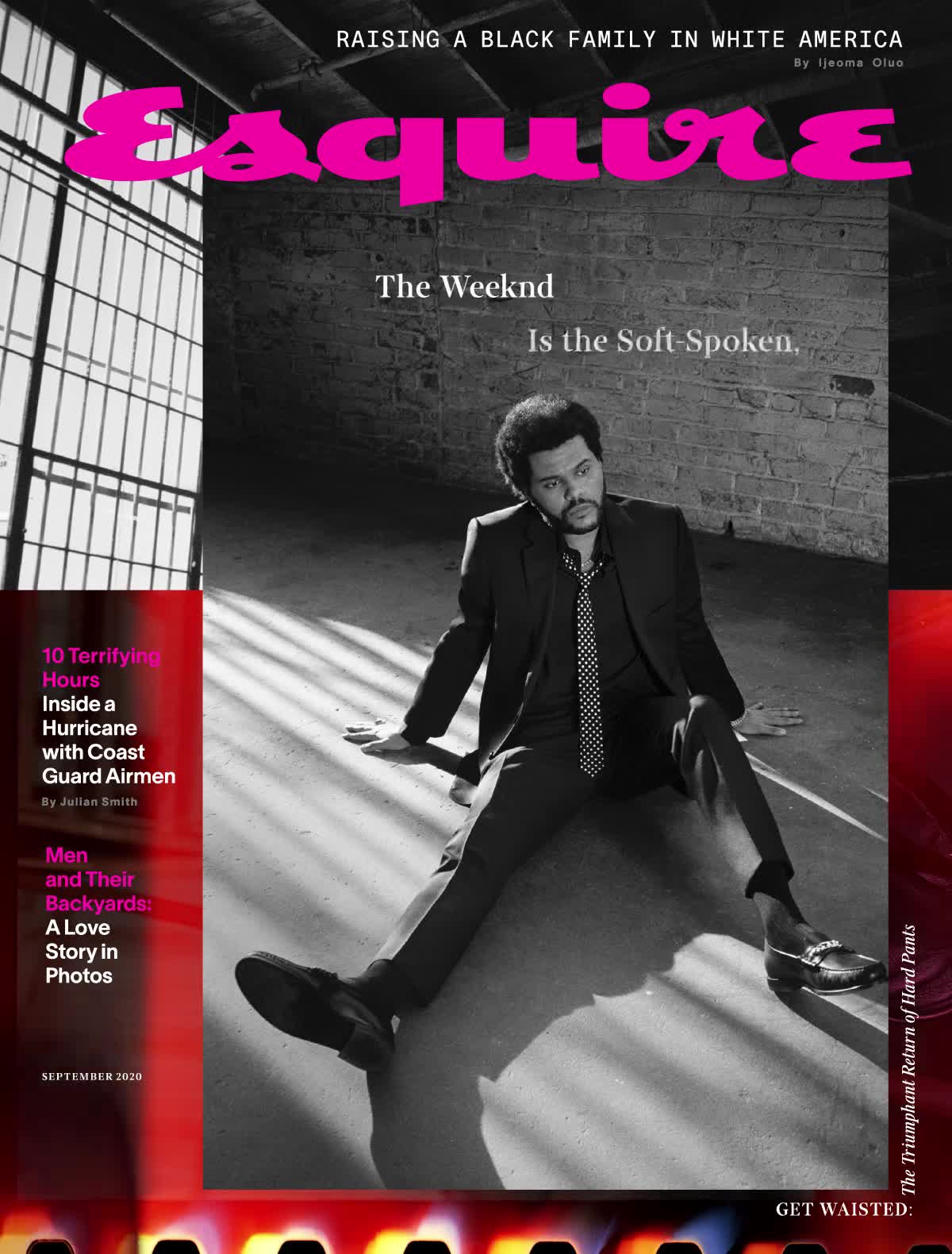

This article appears in the September 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

This was perhaps the moment his personalities split, or at least came to a fork in the road—if his discography allows for some role-playing as armchair psychologist here. He could remain a cult favorite andgo down the path of Beauty Behind the Madness, or he could take the route that would lead him to stadium tours, with 2016’s “Starboy,” his final choice in the little biography we’re constructing together.

The song was an immediate earworm, a Daft Punk/R&B-electropop hybrid all about the extravagances of a lifestyle that Tesfaye was certainly enjoying, fully, at the time. He had shed a certain trademark vocal quality—the one that made him sound like he was singing through a cocaine-fueled postnasal drip. This new voice was polished till it gleamed. His lyrics were a calculated sort of raw—a version of sentiments that had been on songs like “The Hills,” sanded down for mass consumption. The song indicated a total, and necessary, evolution from an old version of himself to a new one (Tesfaye’s Ziggy Stardust or Sasha Fierce). It wasn’t a subtle transition to what the media dubbed his “Michael Jackson phase,” a comparison that didn’t sit well. “There was like a backhanded thing [to the comment] that didn’t feel genuine. It felt like they were setting me up for disaster,” Tesfaye says. “I wanted to transcend. I wanted the music to transcend.”

I’m surprised that he ended his five-song biography there, with a song that came out in 2016, when—

“Well, you only gave me five songs,” he counters when I point this out.

Whether he wanted to include it in his biography or not, After Hours has the song that feels more intentionally autobiographical than anything he’s ever released before: “Snowchild,” a softer track about his Toronto years, his come-up from House of Balloons to Hollywood, and the things that make him uncomfortable about fame.

He calls the song “a period piece”: “I just wanted to make my Dark Knight Returns.” The comic-book reference (and the Easter-egg-filled video, a collaboration with the first Black-owned animation studio in Japan, D’ART Shtajio, featuring an animated Tesfaye) gives it the emotional distance of a superhero-character origin story. It’s almost personal—almost.

True to his core, he still demonstrates astonishingly inventive ways to describe sex (he “give[s] her Philip K. Dick”), but he sings with a new earnestness about everything he wants to leave behind: a $20 million mansion in Hidden Hills, for example. He put his famed nine-bedroom estate on the market, the oft-mentioned manifestation of his reluctance to be in the public eye. (It’s the type of place you live in if you’re rich and don’t want to be seen. You have a pool, and a spa, and a basketball court, and enough rooms for the homies if you never intend to mingle in the real world.)

“All that house, it was never really me,” he says now. He’s swapped the manse in favor of the Westwood condo. “Well, the whole floor of a condo,” he says. These days, mostly it’s just him and his dog, Caesar, a big Doberman who thinks he’s people. “He’s a sweetheart, but he’s super protective. He’ll warn me if somebody’s nearby.”

IN JANUARY, HE PUT ON THE RED JACKET THAT WAS MEANT TO BE THE trademark costume for After Hours and performed the most popular single, “Blinding Lights,” on Kimmel. March 7 was the last time he’d perform it before a live audience, at a taping of SNL.

The album came out when cities were on lockdown. Spring was a chum bucket of collective anxiety, overwhelm, isolation, and heartache followed by a summer of continued uneasiness, plus necessary explosive social and racial uprising. Ambulance sirens seemed to be the only fitting soundtrack. Tesfaye considered, for a nanosecond, postponing the album but ultimately decided to release it. He figured his fans needed a distraction in these weird times, and he ended up with an album that is preternaturally appropriate for being stuck in the house, sweating, panicking, masturbating, and despairing.

Sonically, who is better suited, really? He’s got this seraphic voice that lulls you into songs about the faded late nights and underworlds where all of our deviant impulses propagate and turn us into demon versions of ourselves. Overall, critics have called After Hours his best album yet, though some complained that it was too Max Martin slick when we could have used moody and hushed, too produced when we needed raw, too fast when we needed slow (though that’s not really the Weeknd’s fault; pop music of all moods has been speeding up). But even at his most moms-can-hum-it-too, his lodestars have always been unrest, loneliness, and angsty horniness. Those who listen to the Weeknd fervently or even ambiently weren’t surprised that the album contained a track poppy enough to be the song of the summer and psychotic enough to be the song of this summer. Even when he’s entering a new phase of who the Weeknd is, he remains the modern bard of our most fucked-up times. For the first time in a decade, he feels like he’s accomplished what he set out to do after Kiss Land. He conquered the mercurial synth-wave sounds he’s been experimenting with his whole career. He has finally, at least musically, blended the two parts of himself together: the ambitious, shined-up arena-tour pop star and the narcoleptic fuckboy (both still equally profane). His falsetto soars to high notes that threaten to crack, much like our psyche on a day-to-day basis. “Blinding Lights,” he says, is about “how you want to see someone at night, and you’re intoxicated, and you’re driving to this person and you’re just blinded by streetlights, but nothing could stop you from trying to go see that person, because you’re so lonely. I don’t want to ever promote drunk driving, but that’s what the dark undertone is.”

Three days before the song dropped, Tesfaye broke a five-month Instagram silence to announce that more new music was coming. “TONIGHT WE START A BRAIN MELTING PSYCHOTIC CHAPTER LET’S GOOOO,” he also tweeted. (This was in November, but an evergreen tweet, really.) By June, the song was Spotify’s most streamed song in the world, surpassing 1 billion plays.

“It’s eerie. It’s a little . . .” he says when I mention that the song, the tweet, made him seem like a psychic. “It makes me feel like there’s always, like, a higher being or some powerful beyond being that’s kind of, you know, walking me through life. So yeah, I mean, it is eerie. It’s weird.”

He’s got whiplash right now if he’s being honest, because even with everything that’s been happening, he has to admit that he’s happier than ever. “I can stop worrying, aside from what’s going on in the world, which sucks that I can’t really enjoy my happiness, you know?”

There’s a natural if morbid curiosity about what celebrities are doing in their homes when they can’t leave them. Tesfaye’s interior life doesn’t have the same dog-walking-on-its-hind-legs quality to it that Drake’s Toosie Sliding around his louche mansion has; or Henry Cavill’s uploading videos of himself in a tank top, delts on full display, building a computer, has; or Martha Stewart’s thirst-trapping from a pool in the Hamptons has. Any fantasy about Tesfaye ordering women or drugs or both to a mansion during the pandemic is (disappointingly?) just fanfic.

He’s been working, he says. Really. Writing and recording new music by himself and for other artists. He plays video games, but mostly for research. He’s a film nerd—he makes references to movies on every album—so naturally, he’s watching a lot of them. (He just saw the Korean thriller Burning after so many people recommended it to him.) He’s working on two screenplays, but his ambitions for them are modest. He wants to make small, independent films and maybe write roles for himself to play—maybe.

But it’s not like he’s just sitting alone in a condo with Caesar, writing music and ignoring real life and its consequences. Recently, Tesfaye made a very public gesture in the form of major donations. He gave $1 million to various relief efforts to assist with the pandemic and $500,000 to various Black Lives Matter groups. It wasn’t his first time doing so, but he released a statement about artist responsibility, and about the debt the music industry owes to Black creators. What about his own experiences as a Black man in the industry, and in America? Has he experienced racism?

“I probably have, you know? I probably have for sure. But I try to focus on making it about the music and trying to succeed,” he says evasively. Yet he does admit that while Canada has its own issues with race, they really are nothing like America’s, which are more overt. He has an incredibly tight crew that seems to offer him some protection. “We just don’t rely on others to get us where we need to be,” he says.

Tesfaye just had his first IRL hang the week before we spoke. He reunited with a few of the crew he mentioned, including La Mar Taylor, his longtime friend turned creative director. He hadn’t seen them since the SNL taping. “There was absolutely no fighting it,” he says suddenly, surprisingly earnest. “We hugged each other.” It wasn’t even a very extravagant hang. They simply sat together talking, basically re-creating their group chat in person.

He’s embracing the time, the simplicity, that comes with a life reduced to grocery-store runs and not much else. He also turned thirty earlier this year, and he reports feeling what most people feel at that age: He’s content. He’s got friends and family he appreciates. He’s learning to let go of things that don’t serve him. Perhaps he’s not ignoring the real world, really; it’s just that he’s tightened his ranks, and his existence, so that he controls what comes in and out of his world.

What about his reclusiveness? Is that worth abandoning? Does he still need it? Tesfaye thinks for a moment. “The older you get, the longer in your career . . . you know, I let go of it a lot. Sometimes I go back to it, because I miss it.”

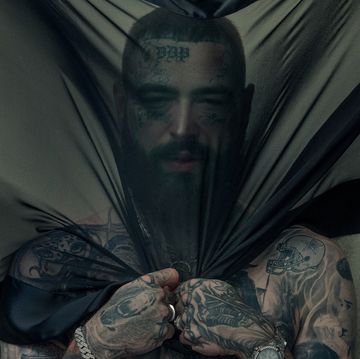

The light has shifted, the sun that was streaming in has disappeared, and he’s been sitting half in darkness for a while, his face shrouded like on one of his old album covers. It’s very dramatic.

But then he stands to turn on a light, fully revealing his bedroom, which sort of looks like a hotel room—flat-screen TV on the wall, white bedding. Reflexively adjusting to the flood of light exposing everything, he lets me know he has only a few minutes left, quickly wrapping up the call.

Maybe it’s the given situation, in a pandemic that is making Intimacy with a capital I a concept worth a second glance. Is it odd to demand intimacy from anyone? Especially a celebrity? Yes and no. Before Tesfaye was this, he was a hushed presence singing the most deviant, secretive feelings and thoughts—his own and other people’s. He sang about millennial sexual discontent the way Taylor Swift sang her diaries—building an expectation from fans that they now can’t shake: that the songs are for them, that the music videos and lyrics are riddled with Easter eggs for them. Maybe he is just a guy who wants to play video games and write screenplays and be left alone, but the experience of him is intimate. His secrecy promises expansiveness and sparks a desire to figure out what’s behind it—is it something that needs to be protected or nothing more than a justified, quotidian quest for privacy?

So, a few days later, we’re talking on the phone and I finally ask him about his reluctance to elucidate things that are so well discussed in the press. Isn’t it better just to clear them up in his own words? He pauses and seems uncertain about how to respond.

“I don’t know, maybe. Maybe it could be that if I feel like I’m reiterating or answering the same question, but I feel like, to me, it’s like, Oh, okay, well, let’s talk about something else. Yeah. Give them something else to talk about, you know? Let’s not keep going back and giving them the same headlines. I mean, I know there’s so much more to me, and there’s so much more to the music, and there’s so much more to everything.”

At this point, if he’s going to address his past, Tesfaye seems to want to do it through parody. He’s even gone so far as to guest-star in an episode of American Dad!, playing himself, but animated and . . . a virgin. It’s a joke that lands best if you’ve, well, experienced his magnetism firsthand. I, for example, once saw Tesfaye perform live at a MoMA garden party and was shocked to find myself blown away by the force of his sexual power onstage. I surprised myself and my date by screaming until my throat was raw. Rather than let others ridicule him as a guy who once said straight-faced in a Rolling Stone interview, “I’ve had a lot of sex,” he’s purposefully holding his past self up for mockery—it’s one way to move past selves that don’t suit us or define us anymore.

He did it again by gamely playing a caricature of his earlier self in the 2019 Safdie brothers movie Uncut Gems. In the film, he dons a wig of his old hairstyle (“It was so hot all the time”), goes to 1 OAK, and has a bathroom hookup with Julia Fox (a good friend of his). I ask him if he could ever go back to any version of that person. “No. I mean, I didn’t really say anything outlandish. I mean, we were all eighteen-year-old blip-blip kids, as you call it.” (He means blipster.) “I’m just growing up now, maturing, learning.”

Playing the Weeknd as a character feels like the equivalent of the mansion in Hidden Hills—another way to stay guarded, distant, to put miles between himself and the rest of the world. He stops to consider why he’s let the Weeknd take on a separate life of its own. He seems stumped.

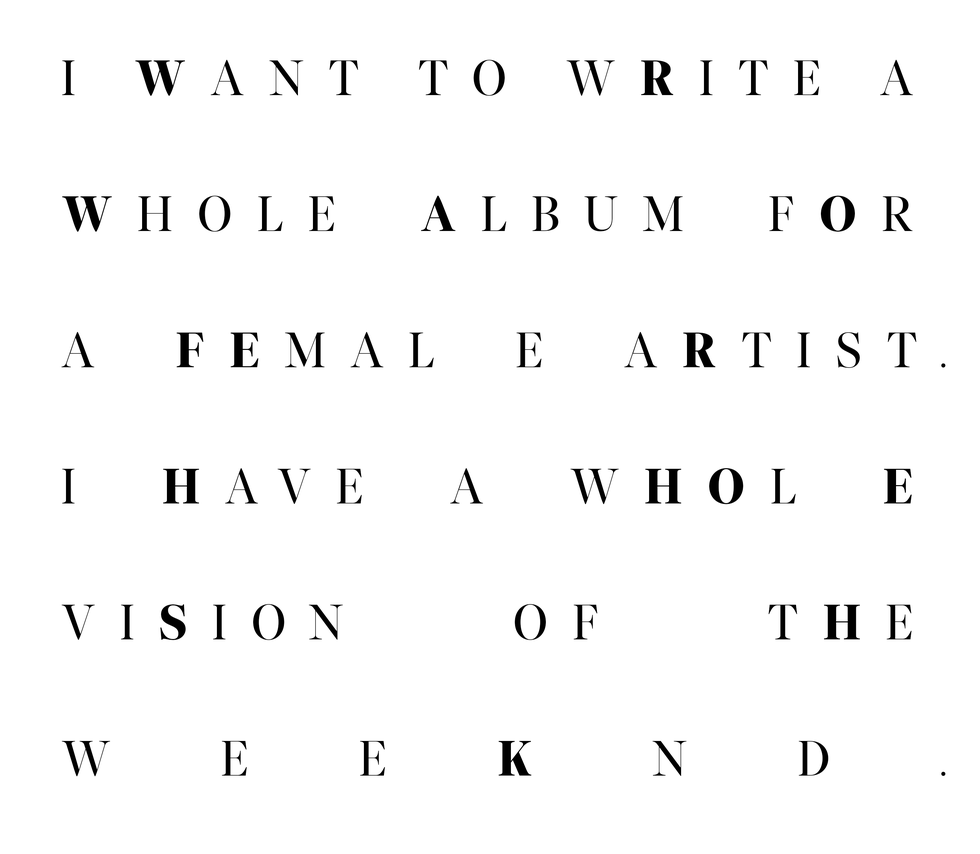

“I’m a writer. Sometimes I write a song and it’s not in my head. I’m writing it for someone else, but then I end up singing it. I want to write a whole album for a female artist. I have a whole vision of the Weeknd. But I guess it’s like . . . it’s the same reason why I want to write for someone else?”

But come on: People have to wonder if this lyric is about that or if this song is about this; was this line, three minutes, twenty-four seconds in, about that Met Gala appearance? When he sang, “I just fucked two bitches ’fore I saw you” on “The Hills,” fans are going to want to know: Does he call women bitches? Did he really just fuck two of them on the way to fucking another (which seems like the sexual equivalent of eating a Double-Double before going to a steakhouse)!? How does he reconcile some of the more misogynistic things he says, like calling women bitches, all the time?

Tesfaye asks me to repeat myself in a way that makes me think the surprise of hearing his own lyrics read out loud to him may have forced him into something he’s never considered—but my video has just frozen. So I ask again: “What of the ‘bitch’?”

“It’s definitely a character. When you hear some of the drastic stuff, you can tell. I mean, that’s why it’s tricky, because it is me singing the words; it is my writing. It’s like you want people to feel a certain way. You want them to feel angry. You want them to feel sad. You want them to feel. It’s never, like, my intent to offend anybody.”

This brings us to an album he definitely didn’t mention in his five-song bio, 2018’s My Dear Melancholy. It was a surprise drop between album cycles that felt more like House of Balloons than ever. Fans declared, “The old Weeknd’s back.” The album cover, with his face obscured, red, emerging from a shadow, felt familiar. Sonically, it was a throwback: twenty-two minutes of concentrated, raw pain; dark and sexually aggressive deep beats that hovered at the RPM of very stoned sex, not dancing in a club; lyrics sung like the feeling was so urgent he’d explode if he didn’t get it out. (It took him about two and a half weeks to write, record, and release the whole thing from scratch.) A perfect breakup album.

It was also peak “Let’s speculate about what’s going on here,” because the album exists in a world where an assumed timeline of Tesfaye’s high-profile relationships has taken shape, where he stopped dating Bella Hadid and was romantically involved with pop star Selena Gomez, who then went back to her ex Justin Bieber. There are multiple blogs dedicated to which lyrics are assumed to be about Hadid (“I hope you know this dick is still an option. . . . You were an equestrian, so ride it like a champion”), which are about Gomez (“I almost cut a piece of myself for your life”), and which are about himself (“Ima fuck the pain away, and I know I’ll be okay”).

He dances away from questions about what was going on at the time, or even what he was feeling, in nonspecific terms, but he calls the album cathartic. “The reason why it was so short is like, I think I just had nothing else to say on this . . . whatever . . . . It was just like this cathartic piece of art. And yeah, it was short, because that’s all I had to say on this situation,” he says, widening his eyes.

Did it make him feel better?

“Yeah, of course. I mean, that would have sucked if I didn’t.”

I bring up the fact that he scrapped a whole “upbeat” album in favor of My Dear Melancholy. What made him do that?

“It’s not my first time. I’ve scrapped so many records!” he responds.

Tesfaye becomes comically taciturn around this kind of thing, never combative, sometimes contrite, mostly just demonstrating that he understands that this is a game, and he’s refusing to play, with commendable stubbornness. I choose to be direct and ask who, if anyone, this album was about. I receive the rarely enacted, truly disconcerting “No comment.” He says it sweetly, almost apologetically, but with the finality of a steel gate dropping over the window of a store.