J. I. Packer: Catechetical Theologian

July 23rd, 2020 | 12 min read

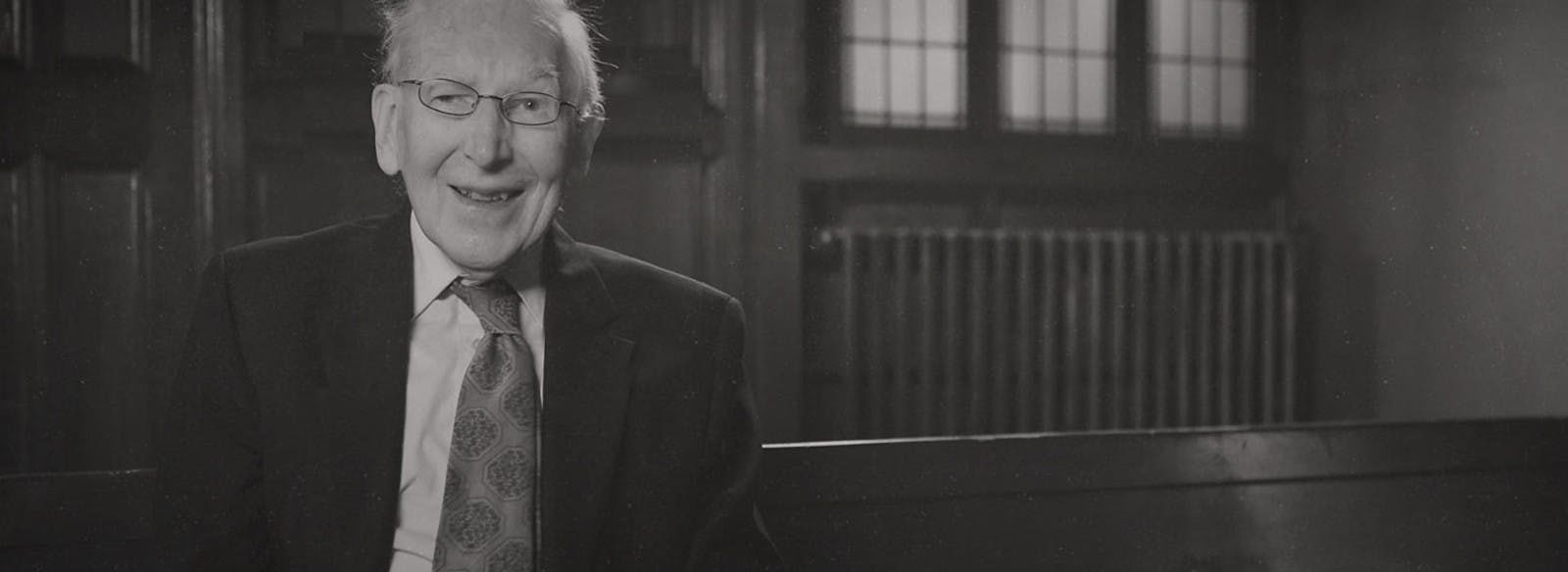

Funny how it hits you when a beloved teacher dies. Almost unbidden, a passel of images, emotions, and memories of moments spent together remind you of the enduring impact that person’s words, deeds, and character had upon you. The effect of a good teacher endures well beyond the last day of class. And if that person spent 65 years teaching and writing, and, in this case, is regarded as one of the most influential Evangelical writers of the 20th century, you can be fairly certain that you are sharing that experience with thousands of people around the globe.

The number of obituaries and memorials that I have seen in the past few days—from his friends, students, colleagues, far-flung readers, and even the Archbishop of Canterbury—testifies to that fact. And no doubt the public remembrances are dwarfed by private ones like the half-dozen messages of gratitude I exchanged with other former students when we learned that J. I. Packer, always “Dr. Packer” to us, had finally been carried through the thin scrim of mortality on his 66th wedding anniversary just shy of his 94th birthday.

What to say? This man touched lives. His words nurtured faith. His example encouraged piety. His wit spread smiles. His gentle humility and steadfast service prompted grateful affection. But despite his widely acknowledged impact upon the global church, the sales of books like Knowing God, being Senior Editor of Christianity Today and the English Standard Version, or being written up in biographies by Alister McGrath (1998) and Leland Ryken (2015), Dr. Packer regarded himself as a simple servant set with a task who tried to do his work well. And last Friday, July 17, 2020 this good and faithful servant entered into the eternal joy of his master, leaving those of us who knew or read him to reflect on the work and example he left behind.

That work was largely the work of a Theologian, but one who took his vocational cues from the Reformation theologians who were ordained for the church rather than the academy. Like them, Dr. Packer was an ecclesial or catechetical theologian. In the 1999 introduction to his Collected Shorter Writings, Packer recalls the vocational wisdom he learned from Martin Luther who, in the introduction to his own collected works, discovered the theologian’s rhythm in the pattern of Psalm 119: oratio, meditatio, and tentatio, that is, sustained prayer for light and understanding, thoughtful meditation upon Scripture, and struggle to remain faithful to the truth in the face of whatever temptation, adversity, or opposition may come. Packer’s conscious attempt “to hew to Luther’s line” is evident in the three manifestations of his vocation as a catechetical theologian: teacher, author, and churchman.

Unlike many others, I knew him as teacher before I knew him as author or churchman. I had read books by his Regent College colleagues, Eugene Peterson and Gordon Fee, and by his friends, John Stott and F. F. Bruce, but before I arrived at Regent in the mid-90s, I hadn’t cracked a single book of Packer’s. Of the 47 he eventually published—roughly one every other year since the day he was born—I have since read several. But to many of us, he was a teacher first. And the first of a dozen courses I took with him could not have been a better introduction to the breadth of his mind and the depth of his heart. It was “Systematic Theology B: Christology, Soteriology, and Anthropology,” a course centered on the embodiment of God’s love in the person and work of Christ on behalf of humanity.

Packer once described the Holy Spirit’s work as shining a spotlight on Christ, but that was Packer’s lifelong work, as well, to carefully, clearly, and coherently explain who Christ was and what he did so that his students and readers might come to love Christ, be grateful their sins were forgiven, and confidently enjoy their reconciliation with God and God’s people. That approach is how a later seminar with him on John Calvin’s Institutes could be one of the most “devotional” experiences of my life. Calvin’s personal seal of his hand offering his heart to God could have been Packer’s. And so Packer began each of his classes with a robust (and brisk) singing of the Doxology, because as he constantly reminded us, doxology is where good theology begins and ends.

Packer didn’t separate his head and heart, or hold himself aloof from his students, as anyone who spent time with him knows. Twice, I saw him tear up describing the 1940 “miracle of Dunkirk” as an act of God’s grace. He shared how listening to “Fats” Waller play piano on the radio as a boy provoked in him the Sehnsucht that C. S. Lewis would later describe as an aching longing for the beauty and Joy of heaven. He was moved that God providentially prompted his parents to give him an old typewriter for his 11th birthday instead of the bicycle he wanted, but which a near-fatal childhood accident had left him too vulnerable to ride. And as he grew older and his body wore out, he openly embraced weakness as the way God’s love and mercy had always been manifested in his life.

Though I never shared his uniquely British love of trains (his father was a railway clerk), and only gradually came to share his love of jazz, we did share a love of literature and Classics (his first degree at Oxford was in “Greats”), and both had families through adoption, which we talked about at length one long afternoon in his front room just as my wife and I were beginning the process. When Dr. Packer finally met our one-year-old daughter, he told her, with eyes twinkling, “You can call me ‘Uncle Jim’.” Many others have similar stories of Dr. Packer’s open warmth and generous spirit.

I eventually became Dr. Packer’s Teaching Assistant after his first choice turned him down (can you imagine?), and spent the next several years typing his notes, researching articles, tutoring students, listening to hundreds of hours of lectures, and occasionally accompanying him to the symphony or house-sitting for him and his gracious Welsh wife, Kit. Thankfully, I only once lost their dog, Cloud, and, even more thankfully, found her again before they returned. One thing I never did, though, was tidy his less-than-tidy office with its stacks of books, papers, letters, and stray royalty checks. A Teaching Assistant before me had made that mistake, and it was made clear to me that such a thing was not part of my job description. If his famously ordered mind did not see fit to order his office, I thought, neither would I.

And though, by both nature and training, his mind was orderly and systematic, in class Dr. Packer never offered textbook surveys of all the available theological positions on a topic and left it to his students to pick one. Instead, he persuasively articulated the view that he thought most true to Scripture and most coherent with the orthodox traditions of the church, usually filtered through the historic Reformational tradition of Calvin, Owen, Baxter, Bunyan, Ryle, and the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. And he didn’t speak in sentences, even extemporaneously, at least not like most of us do.

Instead, he spoke at length in finely crafted paragraphs and essays. That is not to say he was especially long-winded (not usually), but that he spoke until he thought he had sufficiently explained a topic, and would not break for questions until he had done so. When he did pause, he would look around the class and inquire, “Do you see it, too?” And more than once we sat in his office while I fumbled about with some theological question, only to have him very graciously say, “Brian, I think the question you’re trying to ask is this,” after which he would perfectly articulate my question, then ask, “Is that it?”, to which I would usually nod in agreement, and we would begin.

I once asked him directly when he planned to retire from teaching, and he shrugged his shoulders and replied, “what else would I do?” That is the answer of a catechetical theologian who knows he has been called and equipped to serve God’s church and God’s people as long as God allows, whether in the classroom or on the printed page.

And as an author on the printed page is how most people came to know Dr. Packer and benefit from his sustained practice of oratio, meditatio, and tentatio. Because the way his mind worked, there was often little difference between the finely crafted words we heard in class and the finely crafted words his readers read on the page. So the Dr. Packer his students knew in his office, class, or front room was the Packer his readers know from books like Knowing God; Concise Theology; A Quest for Godliness: The Puritan Vision of the Christian Life; Christianity: The True Humanism; Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God; “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God; Weakness is the Way; The Heritage of Anglican Theology (coming in 2021); and so many others. Readers who know these and other works well could, of course, identify a handful of recurring Packer themes:

- Scripture as the totally true and entirely trustworthy Word of God, “profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness;

- The person and work of Christ as entirely sufficient for the forgiveness of sins and reconciliation with God, because “if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him”;

- The lifelong pursuit of sanctification through piety, holiness, and biblical spirituality so that we can “keep in step with the Spirit”;

- Worship as the due response of rational and respons-ible creatures to the self-revelation of their Creator, “for he is our God and we are the people of his pasture”;

- The centrality of the Church, “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets,” to the work of God and the life of the individual Christian.

But though a reader will find echoes of these across the whole of his corpus, the point of reading Packer’s works is not, of course, to know Packer, but to know the God Packer knows and loves.

Finally, Packer’s vocation as a catechetical theologian manifested itself in his life-long dedication to the Church. He was ordained an Anglican priest in 1953, served a three-year curacy outside Birmingham (UK), and regarded himself as a minister of Word and sacrament to the end, regularly leading services, preaching, and teaching in his home church, St. John’s Anglican, where twice I preached while he led the liturgy. But his direct work on behalf of the bride of Christ went well beyond his local parish. After his DPhil at Oxford, he worked at Tyndale House, Latimer House, and Tyndale Hall in the 1960s and 70s with the express intent of strengthening the church through sound theological education. Even his teaching at Regent College, where he arrived in 1979, was oriented toward equipping the church with a theologically sound laity. He explained that Regent’s calling was not to train professional ministers or theologians. That’s God’s business, he would say, not ours. Regent simply offered the best theological education it could and left to God how God would use its students once they graduated.

Packer was also involved in several national and international attempts to strengthen the life and practice of the church, including the 1970 document “Growing Into Union,” arguing for a united Church in England; helping write the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy; writing for the 1990’s Essentials Movement in the Anglican Church of Canada; in the 2000’s supporting the newly formed Anglican Network in Canada (ANiC) and eventually the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA); serving as general editor for the English Standard Version translation of Scripture, and most recently, helping compose To Be a Christian: An Anglican Catechism.

He also worked beyond the Anglican Communion and Protestant church as a central figure, with Richard John Neuhaus and Chuck Colson, in the 1990’s project “Evangelicals and Catholics Together,” and in jointly taught courses with Bradley Nassif on “Eastern Orthodoxy & Evangelicalism in Dialogue,” and with his friend Thomas Howard on “Evangelicalism & Catholicism in Dialogue,” both of which are still available on audio from the Regent College bookstore. More than once during the class on Evangelicalism and Catholicism, Thomas Howard turned to the room of students and exclaimed: “Why don’t you Protestants just get yourselves organized and make J. I. Packer your pope! You’d be a lot better off!” Dr. Packer would just laugh and get on with the much more humble task God had actually set before him: to be a simple catechetical theologian of the church.

Packer’s commitment to Scripture, historically orthodox theology, and the witness of a faithful church did not always please either his opponents or his friends, but whenever he was drawn into controversy, it was always by necessity rather than preference, and always with a sense of “here I stand, I can do no other,” or better, “here is where I think the Bible has taken me, and here is where I must remain.” And though he never sought controversy, when it came, he accepted it as part of the tentatio to which the theologian was called, faithfully and persuasively witnessing to the truth as best he saw it.

When asked in 2015 to reflect on his own legacy, Packer replied, “I ask you to thank God with me for the way that he has led me, and I wish, hope, pray that you will enjoy the same clear leading from him—and the same help in doing the tasks that he sets you—that I have enjoyed. And if your joy matches my joy as we continue in our Christian lives, well . . . you will be blessed indeed.” Whether you encountered him as teacher, author, or churchman, I suggest we follow his lead one more time and thank our gracious God for the ways he used this humble, erudite, and faithful catechetical theologian, James Innell Packer. Requiescat in pace.

Enjoy the article? Pay the writer.

Topics: