Great white place

![]()

Etosha offers that iconic image of Africa: a waterhole surrounded by animals, the very epitome of an oasis teeming with life beneath the merciless sun. Thousands of hooves of every shape and size scrabble over the rocky ground as their owners seek out the life-giving water, while opportunistic predators eye the crowds in anticipation. Long-limbed giraffes assume their awkward straddle, reflected in the shimmering pan, and the imposing figure of a statuesque white elephant looms large, dwarfing the slight springbok in comparison. It is a wildlife photographer’s dream – a scene shimmering in the heat where Africa’s quintessential creatures assemble in numbers that boggle the mind.

Namibia’s Etosha National Park offers this visual overload in abundance, a special kind of wildlife opulence where visitors are spoilt by the opportunity to wait for the animals to come to them.

The Park

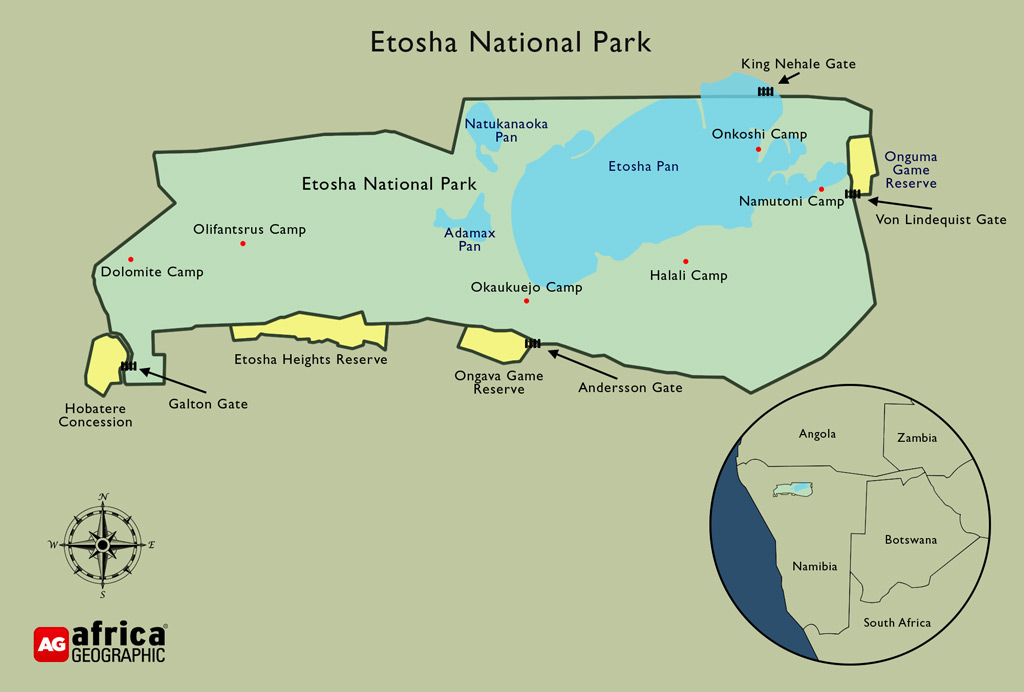

Situated in northern Namibia, Etosha National Park is a fenced reserve that is one of the country’s most popular safari destinations, with the stark otherworldly scenery and spectacular wildlife viewing being the park’s two major drawcards. Proclaimed as a protected area in 1907, Etosha was once the largest game reserve in the world and estimated to cover around 80,000km² (8 million hectares), four times the size of South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Significant boundary changes throughout the 20th century eventually reduced the park to its current size of just over 22,000km² (2,2 million hectares). The park’s eastern side is dominated by the enormous Etosha Pan, while dolomite hills are the main geographical feature of the western half of the park. This western region has only recently been opened to all visitors – it was previously only accessible by local tour operators or guests at Dolomite Camp.

There are six main camps within the park:

- Okaukuejo Camp – the oldest of the camps in Etosha, Okaukeujo (‘the woman who has a child every year’) is famous for spectacular sightings at the floodlit waterhole, particularly of black rhino. This is the busiest of all the camps, both in terms of functioning as the administrative centre of the park, as well as attracting the most visitors.

- Halali Camp – situated halfway between Okaukuejo and Namutoni, Halali offers both chalet accommodation and camping. The floodlit waterhole is the central feature of the camp.

- Namutoni Camp – situated in the eastern half of Etosha, this camp offers chalet accommodation and camping, and there is a raised walkway around its waterhole. However, it is the white crenulations of Fort Namutoni that give the camp a unique and historical character. The Fort was constructed in 1897 as a German military outpost to help control the spread of rinderpest, foot-and-mouth, and other cattle-related diseases. The fort was razed to the ground by an attacking Ovambo force in 1904 but later rebuilt.

- Dolomite Camp – located in the western half of the park, this is an unfenced camp with chalets dotted in the rocks of the dolomite hills. No camping is allowed.

- Onkoshi Camp – along with Dolomite Camp, Onkoshi is the second of Etosha’s more luxurious accommodation options and is entirely solar-powered. The camp is situated on the edge of Etosha Pan itself, and there are no campsites or self-catered accommodation options.

- Olifantsrus Camp – a dedicated campsite without chalet accommodation, Olifantsrus is the newest of all Etosha’s camps and located in the north-western section of the park. The campsite sports a double-story, glass-fronted hide that looks over its manmade waterhole. The elephant information centre bears testament to its history as an elephant abattoir during the 1980s, when elephants were culled by managers concerned about the destruction of biodiversity. Hence the name Olifantsrus translates as ‘elephant’s rest’.

Outside of the park, there are several private game reserves where visitors can enjoy a range of accommodation from luxury, fully catered lodges to budget self-catering and camping options.

The Pan

The park is named for Etosha Pan – an enormous 4,760km² salt pan – visible from space – which makes up nearly a quarter of the national park. The desiccated and bleached soils of the pan are dry for most, if not all, of the year. The word ‘Etosha’ is said to have originated from the Ndonga word for “great white place”, an accurate description of the chalky and desolate landscape.

The original human inhabitants of Etosha were the Hai//om Bushmen people, and they have their own legend as to the history of the pan. According to their mythology, there was once a small village at the centre of the pan that was raided by a rival tribe. All of the village inhabitants were slaughtered but for one woman, who was so grief-stricken that her tears created an enormous, salty lake. The lake dried eventually, but the salt of her tears remained. The likely scientific explanation for the formation of the endorheic basin is that tectonic shifts redirected the flow of the Kunene River and the lake dried up over time – probably around the same time as the formation of the Okavango Delta.

Now, only the Ekuma and Oshigambo Rivers feed the pan with seasonal water and in years of high rainfall, parts of the pan fill to a depth of around 10cm. The pan becomes a breeding ground for thousands of flamingos, and great white pelicans – a spectacle of pink that varies depending on rainfall and reaches its zenith around January and February.

Magic pools and a fairy-tale forest

Life in arid Etosha revolves around the waterholes dotted throughout the park. Many of these are fed by natural artesian springs, but others are manmade, and it is for good reason that the road network in the park is centred around these pivotal features. Apart from the height of the rainy season during the summer months, these waterholes offer the only available water for the park’s multitudinous animal species. As a result, remarkable sightings at the water’s edge are inevitable. For eager photographers and predators alike, the waterholes guarantee a gathering of animals unlike any other.

Regular visitors to the park naturally develop a preference for certain waterholes, and each has something unique to recommend it – whether it is the surrounding scenery, positioning for the best morning or afternoon light, or even the repeated visits of a ‘resident’ leopard. It goes without saying that a good lens (and a familiarity with camera settings) will do wonders to enhance the experience. Still, it’s always important to remember to set the camera aside for a brief period, to soak up the atmosphere. It is also well worth investigating the etymology of the waterhole names, which provide a fascinating insight into the area’s history. For example, Natukanaoka Pan translates roughly as “you need to take long strides to walk here”, or Gobaub which comes from the Hai//om word for a loincloth, supposedly after a man who lost his while beating a hasty retreat from an angry elephant.

Sprokieswoud, meaning “fairy-tale forest”, is also appropriately named for its unearthly scenery. Here thickset Moringa trees (Moringa ovalifolia), usually found on rocky hillsides, dot the landscape and their strange bulbous shapes in the otherwise barren scenery create a dreamlike and surreal atmosphere.

A white elephant

As is so often the case in Africa’s treasured protected areas, Etosha’s animals are a testament to natural resilience. By the late 19th century, the region’s large mammal species, including elephant, rhino and lion had been all but exterminated. Still, mammal life has bounced back over the last century. There are two near-endemic antelope – the black-faced impala (a subspecies) and the minuscule Damara dik-dik with its piercing whistle alarm – not to mention an assortment of other antelope species. Black-backed jackals haunt the waterholes, exploding into action whenever the delicately coloured flocks of sandgrouse arrive to drink, while larger predators like lions and spotted hyena follow similar tactics with bigger prey in mind. Endangered mountain zebra can be found on the slopes of the dolomite hills of Ondundozonananandana (try saying that five times fast – or even once slowly).

The looming figures of the elephants at the waterholes look enormous, and this is not just due to a trick of perspective – Etosha is home to some of the largest elephants in the world. When covered in the white clay soils from around the waterholes, they look like giant grey ghosts, which only adds to their gravitas. While physically enormous, their tusks are generally far smaller than other elephants in different parts of Africa, which may be due to genetics or the mineral balance in their diet, or a combination of both.

Yet is the black rhino that truly steals the show in Etosha. Famously myopic and short-tempered, the park is a stronghold of the world’s black rhino population. Though there are no official published numbers, Namibia is home to around half of the world’s black rhino, and many of these are found in Etosha. Their nocturnal social gatherings around certain waterholes have become almost legendary, turning the myth about black rhino being cantankerous and solitary on its head.

The experience

The Etosha National Park experience is unlike any other safari experience in the world – nothing quite compares to the vast abundance of animals of every shape and size, gathered together in one place at one time. For those for whom a trip will be a once-off treat, it is essential to visit during the dry season, when the waterholes are critical to the life of the park and wildlife viewing is at its best. That said, this is also when the park is at its busiest, and it may well be worth seeking private accommodation in a private reserve outside of the park if large crowds are an unattractive prospect. For those fortunate to return regularly, the park has something to offer all year round, with the added advantage of quieter periods and lower rates during the rainy season.

For camps & lodges at the best prices and our famous ready-made safari packages, log into our app. If you do not yet have our app see the instructions below this story.

Regardless, Etosha National Park is guaranteed to furnish her fortunate visitors with something spectacular – from prime wildlife viewing, to entirely unexpected animal behaviour or, just simply, an insight into Africa’s inimitable seasons and how life adapts.

Further reading: ‘Exploring Etosha’ and ‘Etosha Through My Eyes’

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC:

- Travel with us. Travel in Africa is about knowing when and where to go, and with whom. A few weeks too early / late and a few kilometres off course and you could miss the greatest show on Earth. And wouldn’t that be a pity? Browse our ready-made packages or answer a few questions to start planning your dream safari.

- Subscribe to our FREE newsletter / download our FREE app to enjoy the following benefits.

- Plan your safaris in remote parks protected by African Parks via our sister company https://ukuri.travel/ - safari camps for responsible travellers