Nepal's Earthquake: How Not to Rebuild a Nation

In an environment of poverty and corruption, rigorous building codes do more harm than good

The great tragedy of Saturday's earthquake in Nepal may have taken the rest of the world by surprise, but to many Nepalese, it was only a matter of time. All of the ingredients for a lethal, nationwide disaster in the land of Everest have been in place for ages: high population density, isolated mountain communities, extreme poverty, ramshackle development, political instability, state corruption, and a seismic fault line deep enough to cut through the Himalayas.

As the Nepalese know all too well, there's no easy or obvious fix for any of this. Nepal has spent centuries struggling to resolve its many problems, with results ranging from disappointing to tragic. Ke garne? as the old saying goes, meaning "What to do?" It's a quintessentially Nepalese expression born of perceived political helplessness, usually accompanied by a dim smile and fatalistic wave of the hands.

Far from the gloomy sentiments on the street, experts in the West think they know exactly what to do. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has an optimistic three-year plan to help Nepal develop a regional community of experts capable of establishing mandatory building standards that will minimize earthquake damage. CityLab and the United Nations agree, calling for Nepal to tighten its National Building Code to prevent future tragedies.

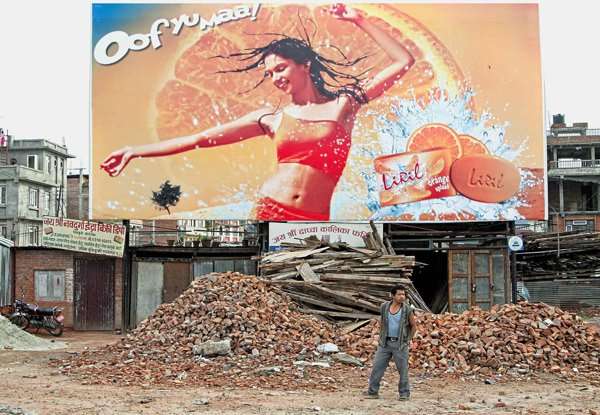

Although the Code has been on the books for twenty years, local builders have been free to ignore it with impunity. Today, most construction remains unregulated. To the everlasting disappointment of Shangri-La-seeking tourists, Kathmandu's slapdash sprawl gleams not with gold, but with corrugated tin rooftops and rusty, naked rebar jutting out of half-finished concrete columns. Even after a devastating earthquake in 1934 took over 10,000 lives, no comprehensive system of building regulations, planning, or enforcement was ever put into effect.

With so much at stake, why has Nepal stubbornly refused to modernize its urban landscape? Buildings designed, engineered, and constructed to withstand earthquakes survive disasters better than those slapped together with shoddy materials and construction. But the real question is always one of tradeoffs and in many parts of the planet insisting on First World construction standards would leave millions without shelter.

Nepal's Ministry of Physical Planning, Works, and Transport Management has even written up its own plans for implementing building standards, but for reasons that should be obvious, they've never gotten off the ground floor.

The first reason is cost. In a country where a quarter of the population survives on an income of less than $1.25 per day, code compliance is beyond the means of millions of Nepalese. For tens of thousands of low caste and landless squatters, known as sukumbasi, the availability of cheap, improvised housing is a matter of daily survival. Yet in supporting the establishment of quake-resistant building codes, journalists often fail to consider the prohibitive cost, and potential damage involved in criminalizing the construction of shacks and shantytowns in one of the poorest countries in the world.

The World Bank looked at the impact of building codes in the "developing" world, considering benefits and costs. For most construction, they advocate a light regulatory touch:

"Regarding building regulations in developing countries, for private homes and other small buildings, it may be that the best default approach is to educate rather than regulate, leaving regulatory construction engineers and planners to focus their efforts on relatively few high-traffic public buildings."

The World Bank made its recommendations without specific reference to Nepal, where the challenges of regulating construction are especially steep. Any retrofitting would have to accommodate buildings that range from modern shopping malls to ancient Buddhist shrines at high altitudes. It would have to create a community of professional structural engineers and standards enforcement that doesn't yet exist.

More crucially, the code would have to function within a system long reviled for bureaucratic ineptitude and endemic state corruption. Not only has Nepal's government been unable to provide a steady flow of electricity to its citizens, for the last eight years the country has stumbled along as politicians have failed to agree on a written constitution to guide the nation.

And now, as protesters rally against the government's inadequate response to the earthquake, it's not even clear whether a national emergency can unite the country.

Are you feeling that sense of Nepalese fatalism yet? Before you wave your hands and cry Ke garne?, know that past disasters offer some hope for the future. Nepal rebuilt some of its old monuments after the 1934 earthquake, and soon added a few new ones. New Road was constructed after the quake, and it quickly became home to the most desirable and prosperous businesses in the city. The absence of expensive building codes may have sped the rebuilding process considerably.

If the central government can maintain a light regulatory touch, new, vibrant communities may yet emerge from the rubble of an ancient Himalayan world.

Show Comments (58)